Done With Dirt

- Share via

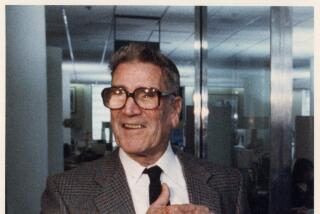

Ten years ago Helmsley entertained hopes of becoming a novelist in the manner of James Joyce. After the failure of his fifth book and his second marriage, he took up a career in journalism and discovered that he had an impressive talent for writing gossip.

Before long, Helmsley was offered a newspaper column. He went everywhere and met everybody. Restaurant owners learned to fear him, and so did the maitres d’hotel of prime-time television. Nancy Reagan sent him birthday cards, and on occasion he was invited to the White House to applaud the magnificence of Oscar de la Renta or George Shultz.

Then, almost as suddenly as he arrived, Helmsley departed. He couldn’t bear to write another line of inane speculation about Dan Rather’s sweaters or Elizabeth Taylor’s next marriage.

Before leaving for Tahiti, Helmsley sent copies of a last testament to several of his acquaintances in Grub Street. Because so much of the talk in the media these days consists of gossip of one kind or another, I thought the reader might find in at least some of Helmsley’s observations a helpful gloss on the text of the news:

“GOSSIP--A means of putting clothes on money. Synthetic substitute for the more demanding forms of literacy, cultural or political discussion in a society that hasn’t got the patience for art or thought. Authors make their reputations by reason of what they do, not by virtue of what they write. Everyone knows that Norman Mailer despises feminists and stabbed one of his wives; nobody can quote a line of his prose. Instead of studying a subject as boring as the Strategic Defense Initiative, people would rather know what Henry Kissinger said to Caspar Weinberger on the way out of a Senate men’s room.

“CELEBRITY--Wealth incarnate. Magazines like People or Vanity Fair, together with television shows like “Entertainment Tonight,” confirm the popular belief that money in sufficient quantity converts the lead of human nature into the gold of commercial personality. It is impossible to imagine such a thing as a poor celebrity.

“GALAS, BENEFITS, CHARITY BALLS--Exist to be photographed. The conversation is excruciatingly vacuous, which isn’t surprising among a collection of people who have little in common except the capacity to pay upwards of $500 for a ticket and $15,000 for a dress. But the next morning in the newspapers, or next week or next month in the magazines, the photographs transform the assembled company into a kind of religious statuary.

“DINNER PARTIES--Analogous to stock markets. If the other people present are richer or more famous than one’s self, then the price of one’s image can be said to be rising; if the other people are poorer or less famous, it is time to buy another oil company or write a new play.

“SLANDER--Nonexistent. Because gossip is about success, the bulk of it is indistinguishable from a press release. The gossip columnist constantly retells Horatio Alger’s tale, welcoming new fortunes into the lighted rooms of the media, counting the cars in the garage and the Picasso drawings on the wall. Unless somebody has the bad luck to fall into the Potomac Tidal Basin or the hands of the police, the columnist refrains from mentioning sexual crimes and misdemeanors. Poverty is cause for scandal; sadism and fraud fall into the categories of charming idiosyncrasy.

“WIT--Impermissible. Because gossip has become a commodity and because it dwells on the very serious matters of net worth, any and all jokes come to be understood as seditious libel. Nobody can be portrayed as a pretentious fool.”

“GOSSIP COLUMNIST--An agent of God’s unfathomable design; an implacable force of nature. At any one time, the media can hold in their collective mind only a relatively small number of images. It is the function of the gossip columnist to maintain the troupe of celebrities in perfect opulence, cutting out the weaker members of the herd and remanding them to oblivion.

Helmsley ended his letter by saying that at a museum opening in November he chatted for 20 minutes to a papier-mache sculpture of Sam Shepard. In his column the next morning, he praised Shepard for the “expressiveness of his enigmatic silence.” After Shepard’s agent called to say that the actor had been in Yugoslavia on the night in question, Helmsley figured it was time to leave town.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.