Fragmenting of N.Y.’s Intellectual Elite

- Share via

Prodigal Sons: The New York Intellectuals and Their World by Alexander Bloom (Oxford: $25)

For three decades, these prodigal sons (assisted by a few daughters, wives and great friends) functioned as cultural gurus; intellectual envoys to the provinces. Though the impact of their ideas and opinions was greatest in New York where most lived, taught, wrote and endlessly debated the social, political and aesthetic issues of the times, their influence was felt across the country.

If you were a humanities major between the 1940s and the 1970s, you read Lionel Trilling’s “The Liberal Imagination: Essays on Literature and Society” and Alfred Kazin’s “On Native Grounds” in English classes; Nathan Glazer and Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s “Beyond the Melting Pot” and Paul Goodman’s “Growing Up Absurd” in Sociology.

The reserve shelf for your courses held disintegrating issues of the New York intellectuals’ journals: Partisan Review, Commentary, and Dissent, augmented in the ‘60s by the New York Review of Books, and for the British perspective, Encounter. If your college wasn’t too far west of the Hudson, one or another of the group might appear on campus, bringing contention and stimulation to the geographically underprivileged but academically deserving.

Concentrating on Interaction

Alexander Bloom, who teaches history at Wheaton College, has written an exceedingly thoroughgoing study of this group, discussing their backgrounds but concentrating upon their interaction with one another, which was constant, passionate, intimate and often abrasive. The basic cohort included Lionel Trilling, Alfred Kazin, Leslie Fiedler and William Phillips; the sociologists Daniel Bell, Seymour Martin Lipset and Nathan Glazer, the art critics Clement Greenberg, Harold Rosenberg and Meyer Shapiro; the political philosophers Sidney Hook and Irving Kristol, and the highly conspicuous editors of Partisan Review and Commentary, Phillip Rahv and Norman Podhoretz.

From time to time, this coterie was enlarged by honorary members Dwight Macdonald, Mary McCarthy, Midge Decter, Diana Trilling, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Lionel Abel, and the writers they extravagantly admired and fiercely disparaged; Saul Bellow, Delmore Schwartz and James Baldwin. Though many other magic names are mentioned, the group remained small and closely knit.

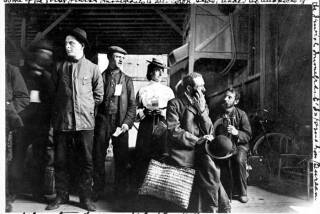

While Bloom emphasizes the differences among the members, the similarities of origin and education are striking. Most were the sons of Jewish immigrants; alumni of New York public schools and either Columbia University or the City College of New York. Profoundly affected by the Depression, almost all became ardent believers in socialism during the 1930s; many leaning toward a more radical left. Socialism not only seemed to offer the hope of a fairer, better world but also presented a panacea for the isolation they felt as precocious intellectuals in a world where the struggle for economic survival was paramount.

‘Passionate and Detached’

“Clearly personal elements drew both the passionate and detached Jewish intellectuals toward radical causes. There certainly existed a belief in . . . reform or revolution . . . Beyond this, there can also be found attempts to overcome their unique and often lonely position. The social aspects of American radicalism has often been demonstrated, from the communitarian societies of the mid-19th-Century to the Communist Party summer camps of the 1930s . . . The movement provided a special community. Having drawn away from their former world, they sought grounding in a new one.” As Arnold Beichman candidly admitted “You could meet a Soviet counsel at a party at Max Lerner’s house. You met a lot of nice girls that way, and some not so nice.”

A Turn to the Right

During those early years, the Prodigal Sons were busily putting their traditional backgrounds behind them, though they would retrieve their heritage in the aftermath of World War II and the Holocaust. As they matured, their youthful radicalism dissipated; most moving toward a moderate liberalism; several swerving all the way right to become strident spokesmen for the New Conservatism.

After meticulously tracing the history of the three major opinion magazines from inception through growth and change; reporting upon conflicts and enmities dividing this once congenial society of thinkers and writers, Bloom discusses events that fragmented the group still further. In his view, those were the New York teachers’ strike of 1968, which exposed deeply buried and repressed ethnic antagonisms; the publication of Hannah Arendt’s “The Banality of Evil,” easily the most controversial book of the era, and the appearance in 1967 of Podhoretz’ confession “Making It,” in which he not only acknowledged his own desire for worldly success and celebrity--”a dirty little secret”--but attributed the same mercenary ambitions to the entire intellectual group, who until then had cherished the illusion they were above such reprehensible motives.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.