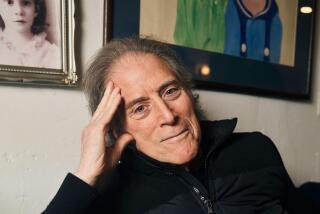

Harry Ritz, 78, Member of Zany Vaudeville Brothers, Dies

- Share via

Harry Ritz, who launched a career in vaudeville by hollering “please don’t holler” and then led his two brothers through a series of zany, knockabout films, died Saturday in San Diego.

Ritz, at 78, was the last of the zany Ritzes. Brother Jimmy died in 1985 and the oldest brother, Al, in 1965.

(A fourth brother, George, also deceased, was in the clothing business.)

Ritz, who had cancer and suffered from Alzheimer’s disease, died of pneumonia.

Although never as successful as their rivals, the Marx Brothers, the look-a-like Ritzes brought a brand of wanton insanity to films and nightclubs that made them favorites for 35 years. And Harry, called by Sid Caesar “the funniest man of his time,” was the acknowledged ringleader of that garrulous gang.

The three began as precision dancers with Al scoring the initial success when he won a series of ballroom dancing prizes in Brooklyn where the brothers were raised. Their mother was from Poland and their saloon-keeper father was from Austria-Hungary. They took the name Ritz off a passing laundry (or cracker, depending on who was telling the story) truck when an agent told them that their given name of Joachim was inappropriate for billboards.

They first teamed as a dance act in 1925 and appeared on local stages mocking a then-popular comic strip, Harold Teen. They wore baggy white pants, out-of-proportion bow ties and perched beanie caps atop their heads, accentuating their ample proboscises.

By 1929 they had made their way into big-league vaudeville, had adopted “Collegiate” as a theme song and had taken to pushing each other around on the stage.

Harry stood in the middle singing “The Man in the Middle Is the Funny One,” a song written for them. The other two brothers would then take to berating him for occupying that favored spot and, as they screamed their displeasure, Harry would wander about bellowing “Don’t holler--please don’t holler.”

By 1930 they were playing the Palace where the headliner was Frank Fay and his bride, Barbara Stanwyck.

They worked in Shubert shows for a time and in 1932 caught the attention of Earl Carroll who featured them in his “Vanities” that year. They were appearing at the old Clover Club on Hollywood’s Sunset Strip when Darryl F. Zanuck reportedly caught the act and signed them to a contract. (Al had appeared earlier in a silent film, “The Avenging Trail” in 1918.)

Their first film, “Sing Baby Sing,” in 1936 was a spoof of a drunken Shakespearean actor (Adolph Menjou) pursuing a nightclub singer (Alice Faye) and the Ritz brand of slapstick was regarded as an integral part of the movie’s success.

In his series “Whatever Became Of . . . ?” author Richard Lamparski remembered them as gentler comics than the Marx Brothers, doing takeoffs rather than putdowns.

Critics generally agree that their early films for 20th-Century Fox were their best; that their later work at Universal suffered by comparison. The brothers had left 20th in a dispute over material. The three farceurs appeared in 15 films, quitting after “Never a Dull Moment” in 1943 to concentrate on club dates.

The Ritzes, among the first of the big-money acts in Las Vegas, made a few television specials in the early 1950s. They carried their zaniness on the road until 1965 when Al died in New Orleans where they were performing. Harry and Jim stayed together briefly, taking their bows with a silhouette of Al beside them and saying “the three of us thank you very much.”

But the club business had peaked and Harry and Jim made two final film appearances (“Blazing Stewardesses” and “Won Ton Ton--The Dog Who Saved Hollywood”) before breaking up the act. (Harry by himself did “Silent Movie” in 1976.)

Since then Harry--the man who encouraged Milton Berle to wear dresses to help hype the laughter when he went on television; the comic who introduced the nervous, nonsensical scat singing that Danny Kaye emulated for years, the entertainer whose mannerisms were adopted by Jerry Lewis--had lived quietly in San Diego with his fourth wife, Naomi.

He was deeply depressed during his last years, she said. “He was just in a deep, deep pit, like deep. He cried,” she said. “He was finished. The Harry Ritz the world knew was over. The sense of humor--gone.”

Death came at 5:30 p.m. Saturday. He was at home.

Ritz was still himself in 1966 when the producers of “Hollywood Palace” were after him to work regularly on their television variety series.

He turned them down.

It Wasn’t the Money

It wasn’t the money, Harry said in an interview with The Times. It was the nature of the medium.

“They want everything held to five or six minutes. How can I do that when my entrance alone with me laughing at me takes five minutes?”

Funeral services have been tentatively set for Wednesday at the Hollywood Cemetery. The family suggests that in lieu of flowers donations be sent to the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce to help fund a star on Hollywood Boulevard for the Ritz Brothers.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.