ORANGE COAST COLLEGE SHOW : TAP REVIVAL HAS DANCER JIMMY SLYDE ON HIS TOES

- Share via

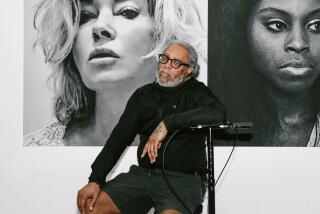

Like many veteran tap masters, Jimmy Slyde prefers dancing to talking.

“I’m not very big with talk, dissertating,” Slyde said in a recent phone interview from his parents’ home in Boston. “I really like my feet to do the talking.

“Besides, a lot of people just use an interview to tell you how wonderful they are.”

But Slyde is more modest.

He downplays his role in the creation of an individual style--dazzling slides, spins and skimming steps across a stage--that can be seen when he participates in the “Rhapsody in Taps” program to be presented by the LTD/Unlimited Dance Company at Orange Coast College on Saturday night.

“Slides and things like that (just) came about after living in the northeast with a lot of snow and ice,” Slyde said.

“I wasn’t a street dancer. I studied. I went to a wonderful teacher, Stanley Brown, who had a studio around Boston, when I was about 10. And a good friend, Eddy Ford, who taught there, instructed me. He augmented the slides and put them into his routines.”

(Slyde also wanted to give credit to Raymond Winfield--”one great slide dancer who was in ‘Tip, Tap and Toe,’ one of the great acts in show business.”)

Until his recent return to this country, Slyde had been living in Paris for more than 15 years, a legacy of the indifference with which America treated tap in the 1950s.

Better recognition is coming. Slyde is one of three tappers featured in the recent George (“No Maps on My Tap”) Nierenburg documentary, “About Tap,” narrated by Gregory Hines.

He also appeared in the Judy Garland version of “A Star Is Born” (1954), toured the country with the Original Hoofers in “1,000 Years of Jazz” and was featured in the jazz-tap review “Black and Blue,” among other achievements.

Slyde was born in Atlanta and moved to Boston when he was 2. He began studying the violin as a child because his mother liked the instrument and thought music was important. “But I was athletic, and the violin was a little staid for me. I liked something very active.”

Eventually that athletic interest took him to Shaw University in North Carolina on a football scholarship.

“I was kind of small for a football player, but I had a lot of heart. I was there for two years. And I continued dancing. I would entertain in school. That kind of let me know that’s where I wanted to go.”

But his musical training proved invaluable to his career.

“You have to have a good basic musical knowledge,” he said. “You learn to play piano, drums or any instrument and your rhythm comes from that. Many people think it’s old-fashioned to count, ‘1-2-3-4,’ but you have to know time.

“Timing is everything, I say.”

Slyde described himself as a rhythm tap dancer.

“I innovate and put the slides into the steps. I try something different each time. A lot of people called it ‘improvisation.’ But I don’t like to use that term. People say when they make a mistake, ‘Oh, I improvised.’

“I (just) try to do it a little different each time, to venture a little more. I try to think as I dance.”

Slyde likes the interaction between a tapper and a band.

“It’s so easy when you work with greatness--with the Duke Ellingtons, or the Bassies, the Ray Browns--those kinds of orchestras. . .,” he said. “You’re catching up. They’re going on, you’re trying to do your best to stay with it.

“It makes a difference with younger musicians. Then you have to rely on yourself to keep yourself good. But accompaniment is not the most important thing. You can’t blame anybody for your own shortcomings.”

Slyde’s performance on Saturday will mark an infrequent appearance in a state where his career was marked by a long struggle.

“I went out to try the Hollywood scene,” he said. “Being a young man, having your dreams, you see movies, you look forward to getting to the area, it’s all part of the dream. But it wasn’t too lucrative.

“It would seem there would be a lot of opportunities for dancers. But it was never really that open an industry for blacks.

“It wasn’t only just me, it was a lot of people. I saw a lot of wonderful dancers. We suffered together,” Slyde said. “I don’t have any bitterness. It was challenging. It makes you tough. It’s still a wonderful industry. It just wasn’t ready for me.”

Still, Slyde left the country in the late 1960s and went to Europe where, he said, audiences proved more appreciative.

“That’s when things started. I did a tour of Europe with a little jazz unit--The Adventure of Jazz. I did a nice bit with Pappa Joe Jones and George Benson who wasn’t that well known at the time. I became a little bit of a name over there. Tap is very big there.”

Slyde hedged on the question of whether tap is strictly a black American art.

“That varies,” he responded. “It mainly depends on a person’s willingness and their own aspirations. Many people can learn things. People can overemphasize that tap is the greatest art or only an American art form. It’s just a matter of anybody wanting to learn. We’re not limited.”

Slyde is pleased with the current revival of tap.

“I’m very happy now. There’s a lot of acclaim for people who put their heart and soul into it.

“People finally know that they (tappers) existed and made contributions. Up to now there has been a lot of emphasis put on ballet, modern, jazz. I don’t think tap has been given the boost that it rightfully deserves.

“I’m not knocking ballet or anything, but tap should have a place in history. People should be aware of it.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.