For the Prince of Darkness, Cold Water on His Cold War Visions

- Share via

Richard Perle’s resignation from the Defense Department marks the end of an era in Soviet-American relations.

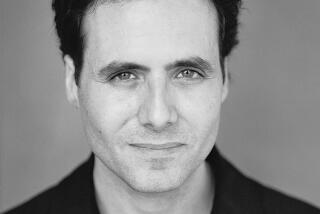

His opponents often referred to him as the “Prince of Darkness” for his role in maneuvering the Reagan Administration to support his vision of the United States locked in conflict with the Evil Empire. But his successes over the past six years were more a product of the times than of his consummate bureaucratic skills. The times have changed, and his room for maneuver has diminished.

Perle based his policies on hostility to the Soviet Union, and he prospered when Moscow lived up to his image as the Focus of Evil. But Soviet leader Mikhail S. Gorbachev has created a new image for his country, and the promise of a new reality as well.

It is too soon to determine the extent of change in Gorbachev’s Russia. But it is clear that Perle has little interest in encouraging changes in Soviet society, since his entire career has been based on responding to the Soviet threat, rather than reducing it. Perle’s fortunes have declined along with the declining public perception of the Soviet threat.

Perle entered public life in the late 1960s as an advocate of the Safeguard anti-missile system that President Richard M. Nixon ultimately sacrificed on the altar of arms control. During the 1970s he was the chief aide of Sen. Henry M. Jackson (D-Wash.), and together they sought to reverse the course of detente with the Soviet Union first charted by Nixon. But the nation had wearied of the Cold War, and their efforts were rewarded with meager results.

By 1979 Perle’s fortunes had improved. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan fulfilled his image of communism on the march and imperial Russia moving toward warm-water ports. Perle had criticized the SALT II treaty because it failed to reduce Soviet missile forces. In the wake of the invasion, President Jimmy Carter declined to seek ratification of the SALT II treaty.

Ronald Reagan entered the White House with a mandate to restore America’s pride. Perle translated this mandate into a determination to renew the Cold War with the Soviet Union.

Arms control was a major obstacle to this renewed conflict, and Perle perfected the art of frustrating progress on arms control. It was often said that his definition of an acceptable arms-control agreement was one that would be unacceptable to the Soviet Union. In this spirit he authored the “zero option,” which called for the elimination of all intermediate-range missiles in Europe. This was instrumental in preventing an agreement limiting these weapons early in Reagan’s first term.

The long struggle against SALT II demonstrated the limits of Perle’s mandate. In 1980 Reagan campaigned against the treaty, calling it “fatally flawed.” But, once in office, he continued to abide by its limits. Despite increasingly strident accusations of Soviet cheating on the terms of the treaty, the United States continued to comply with it until late last year.

With the demise of SALT II, Perle was free to turn his attention to the anti-ballistic-missile treaty of 1972. But the supporters of this treaty proved more formidable. SALT II was negotiated by a Democratic President and never ratified by the Senate. The ABM treaty was signed by a Republican President and ratified by an overwhelming majority of the Senate.

Rather than directly confronting the ABM treaty, Perle sought to undermine it by reinterpreting its terms. At his instigation the Administration announced its “broad interpretation”--that the treaty did not apply to the exotic weapons of the Strategic Defense Initiative. This had the effect of notifying the Soviets that the United States would not be bound by the treaty.

But there were several obstacles in Perle’s path. His new version of the ABM treaty contradicted the testimony of those who negotiated it. Sen. James L. Buckley, a Conservative-Republican from New York, had voted against the treaty in 1972 precisely because it would have limited exotic weapons such as lasers in space.

In January, Perle lectured the European allies for their failure to follow his hard line against the Soviet Union. In February, along with Ambassador Paul H. Nitze, he visited a number of European capitals in an effort to persuade them of the merits of his designs on the ABM treaty.

But the clear message from the allies, perhaps in revenge for his recent lecture, was that there was no support for his latest effort to destroy the only remaining strategic arms-control agreement. The final blow came on Wednesday, when Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman Sam Nunn (D-Ga.) announced that after a long study he could not support Perle’s new version of the ABM treaty.

Perle’s retirement from the Pentagon has long been anticipated, but it is fitting that it should come only days after it became clear that his goal of eliminating the ABM treaty would not be realized. It is also ironic that he leaves at a time when Gorbachev’s recent proposal on Euro-missiles accepts the zero option that Perle had intended to be unacceptable five years ago.

Perle has failed in his life-long goal of ending the arms-control process. This is not so much a result of the limits of his own political wiles as it is a testament to America’s rejection of his vision of the Soviet Union.

DR, Ahle

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.