Kissinger the Revisionist : His Counsel Risks Derailing Reagan’s Arms Control

- Share via

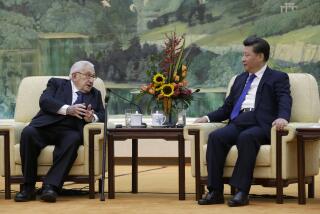

Henry A. Kissinger’s important service to our nation needs no recitation; his auto-biographies provide a brilliant and effective apologia. Yet his very eminence in our national debate obliges others to take account of the erratic course that his views have taken over the years. The evolution of his thinking on nuclear strategy and arms control is perplexing; it gives one pause when assessing his negative counsel on President Reagan’s unprecedented opportunity in arms control.

In the early 1970s, after the initial SALT agreements were concluded, Secretary Kissinger suggested that no one had told him what a world with multiple-warhead missiles would be like. In fact the Senate had done so, by an overwhelming expression of concern that the negotiations must address the MIRV problem in timely fashion. But Kissinger resented that congressional recommendation and ignored it.

The proponents of MIRV, including not only Kissinger but also his frequent nemesis, Richard N. Perle, saw political leverage in the program. Even though the superpowers had curtailed the missile defenses that the multiple-warhead technology was designed to penetrate, its advocates chose to exploit the program without regard to the prospect that a Soviet-American competition in such technology would generate the awesome arsenals now threatening us. A decade later Kissinger was joining the call for de-MIRVing the missile forces to cure the problem created by the earlier mistake.

For some years now those who urged us to enter the world of MIRV have assailed the drastic increases in nuclear weaponry spawned by the ill-considered technological innovations that they endorsed. Yet a number of them, notably Kissinger, have simultaneously seemed contemptuous of practical measures to begin redressing the trends toward ever-more-numerous strategic forces.

In 1979 Secretary Kissinger’s pronounced skepticism about the SALT II treaty, coupled with demands for amendments and collateral conditions, was one of the factors that bogged down the ratification process. Even though that accord incorporated and went beyond the Vladivostok agreement, which President Gerald R. Ford had reached with Leonid I. Brezhnev in 1974, Kissinger and Gen. Alexander M. Haig Jr. chose to stress its inadequacies. Their position made it difficult to forge a bipartisan coalition to treat the modest force reductions required by SALT II as a useful first step toward more meaningful constraints on nuclear capabilities. Instead of expediting negotiations on the many critical issues that remained to be addressed, Americans found themselves divided by lingering disputes over SALT II.

Of late, Kissinger has conveyed a more general condemnation of arms control. He has cast doubt on the value of reducing the scale of nuclear deployments. What difference does it make, he asks, whether there are 11,000 strategic warheads on each side or 6,000, as proposed at Reykjavik?

That is the wrong question. It makes little sense to think of these destructive capabilities only in narrow military terms. Even with 6,000 warheads each, the Soviet Union and the United States will retain physical power beyond imagining. The crucial question concerns their likely political behavior in the presence of such forces: Will the two governments be able to muster mutual restraint in a highly threatening environment marked by large increases in their deployments, perhaps to 15,000 weapons each in the early 1990s, or will they facilitate restraint by cooperating to regulate a menace that they do not know how to eliminate?

It is hard to see how an unregulated strategic contest will improve our capacity to manage the frictions and contradictions that will persist in Soviet-American relations. Antipathy toward President Reagan’s efforts to achieve substantial force reductions works to undermine a historic opportunity to stop the upward spiral of offensive forces--an opportunity that neither Kissinger nor I nor anyone else was able to create during our time in office.

Kissinger’s current stance is nowhere so pernicious as in his astonishing revisionism toward the anti-ballistic-missile treaty. He acknowledges that, although he has not reviewed the documents, the Administration in which he served submitted the treaty to the Senate with a “narrow interpretation.” But the former secretary of state asserts--mistakenly, as Sen. Sam Nunn has now demonstrated authoritatively--that the Soviets adopted the “broad interpretation” from the outset, and that the United States should now do the same. Does this mean that he and his associates did not know what they were doing in 1972, or that they misled the Senate by setting forth an interpretation of the treaty other than the one agreed to with the Soviets? Neither, one suspects. Rather, Kissinger’s personal position has changed as he has come to look fondly on the Strategic Defense Initiative, another of the technologies that periodically excite his fancy.

On several levels that belated hostility toward the ABM treaty is unfortunate. In claiming that the Soviets favored the broad interpretation, Kissinger refers to a single remark by former Defense Minister Andrei A. Grechko: that the treaty “imposes no limitations on the performance of research and experimental work . . . .” That statement is scarcely different from the testimony by U.S. military officials who made clear the wide latitude for research and development at fixed sites on the ground. It is quite compatible with the fundamental interpretation presented by both governments at the time. As Acting Foreign Minister Vasily V. Kuznetsov said to the Soviet Presidium just before Marshal Grechko spoke, “The sides pledge themselves not to create or develop ABM systems or components emplaced in the sea, the air or space, or of a mobile ground type . . . .”

Grasping at the Grechko statement to justify reinterpretation of the treaty is less troubling, however, than the cavalier attitude of treaty revisionists toward American constitutional practice. Most Americans agree that Congress should grant the President considerable deference in foreign policy. For such deference to endure it must be reciprocated. To condone the notion that a President can sell a treaty on an interpretation that he or his successor can subsequently alter would render meaningless the Senate’s power to offer advice and consent. That is not constitutional government; it is despotism.

There is a compelling argument that, for the United States, the only lawful reading of the ABM treaty is the one on which the Senate based its approval. If the executive branch wishes to reverse interpretations, the treaty itself provides for negotiated amendments to be considered by the Senate.

Kissinger’s fluid posture on the treaty relates, of course, to his interest in SDI. While demanding that the Reagan Administration devise a negotiating position that “reflects a long-range national strategy,” he contends that such a strategy must include a prior commitment to proceed with SDI testing and deployment free of any qualitative restrictions. As a lawyer would say, that conclusion presumes a fact not in evidence--namely, that we know how to integrate SDI into a sensible strategy. Neither Kissinger nor any other SDI advocate has explained how to do that.

After several years and billions of dollars, no one has begun to answer the most elementary questions of how we and the Soviets might make the transition to a new strategic relationship built on SDI. What we do know, to paraphrase Defense Secretary Caspar W. Weinberger, is that if the Soviets were moving to install the kinds of SDI systems that we are seeking, the United States would be bound to expand its offensive capabilities dramatically. And I would add that if the Soviets were propounding the revisionist view of the ABM treaty to justify such actions, I would be leading the parade to announce U.S. withdrawal from the agreement.

This is in no respect a partisan issue. Three secretaries of defense who served in the Nixon and Ford Administrations--Melvin R. Laird, Elliot L. Richardson and James R. Schlesinger--have joined in urging the two governments to adhere to the traditional interpretation of the treaty. They do so because they recognize that restraining defense is essential both to maintaining the effectiveness of our strategic deterrent and to reducing the scale of offensive forces.

To base policy, as Kissinger proposes, on the premise that SDI must be tested and deployed is to bet the nation’s security on unproved technologies that we may not be able to afford and our adversaries may be able to defeat. It is to destroy the still-primitive foundations on which diplomacy now has its best chance to shore up strategic stability by prudent force reductions. And it is to serve the President badly by playing to his prejudices without confronting the plain facts that make so improbable the achievement of the all-encompassing SDI that he imagines.

What tragic irony if those who sold us MIRV as necessary to overwhelm non-existent defenses would now sell us SDI as necessary to meet the thousands of warheads bred by MIRV! Responsible policy must forswear technological escapism.

What we need to help President Reagan understand is that the ABM treaty already affords ample scope for exploring technologies that might someday play a role, but his singular opportunity is to improve his successors’ strategic options by beginning a process of agreed reductions in offensive forces. If he misses the opportunity to curb offenses, there is virtually no likelihood that defenses will be able to handle the continuing expansion and diversification of the threat. If the President’s hopes for SDI are ever to bear fruit, they must be rooted in Soviet-American cooperation to shape a new balance between offense and defense.

I share Henry Kissinger’s disappointment that all of us who have worked so long with the nuclear dilemma have not yet devised satisfactory remedies. But politics cannot indulge its frustrations by passing the buck to technology. If we are to escape strategic calamity, technology must be an instrument of diplomacy, not a substitute for it. At no moment in the nuclear age has it been so vital for diplomacy to discipline the weapons that are forever poised between serving our security and subverting it.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.