MAKING A DIFFERENCE : Doctor to Be Honored for Efforts to Change Medical Establishment Attitudes Toward Homosexuals

- Share via

At a time when it was unpopular to do so, he stood up before the medical establishment and said that being gay should have nothing to do with one’s ability to practice medicine.

--Frank Newman,

Co-chairman of Laguna Outreach

Dr. Max Schneider says the most “magnificent and frightening” experience of his life occurred eight years ago, in a time he calls B.A.--Before AIDS.

Schneider, an Orange County internist, had asked to speak to the board of the Orange County Medical Assn. to inform members that 10%-13% of the general population had medical needs related to their homosexuality, and that gay and lesbian doctors were meeting for mutual support in an organization he co-founded, Southern California Physicians for Human Rights.

He told them of a young homosexual man with a serious sex-related medical problem who had received only a moral lecture from his doctor. He told them that homosexual medical students fear expulsion if discovered. And, in what amounted to a major public confession at the time, he also revealed that he himself was homosexual.

“He handled it with a courage and a maturity and a strength and a calmness which I always admired a great deal,” said Dr. Stanley van den Noort, former dean, and now professor of neurology, at the California College of Medicine at UCI, who was sitting on the board that day.

The medical establishment responded favorably to Schneider’s talk. But there were “doctors within the gay community who resented it, who felt we should continue to abide by society’s unwritten rule that it’s OK to be gay as long as you don’t make a point of it,” said Werner Kuhn, director of the Gay and Lesbian Community Services Center of Orange County. But since that time, his organization, which now has about 100 members in Orange County, has played a pivotal role in motivating the medical establishment to address the needs of the homosexual community, particularly in the fight against acquired immune deficiency syndrome, Kuhn said.

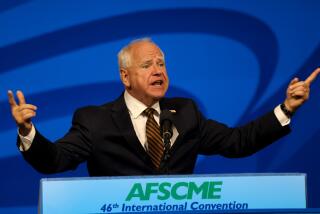

Subject of Roast

On April 11, Schneider, 64, will be honored “for his two decades of support and leadership of the struggle for full human and civil rights for lesbians and gay men” in a good-natured roast at a fund-raising dinner sponsored by the Gay and Lesbian Community Services Center. It will be the first award presented by the center, a social service agency based in Garden Grove that offers counseling, support and educational programs to both the homosexual and general communities in matters relating to homosexuality. Proceeds from the fund-raiser will be used to establish an endowment fund to expand the center’s programs to teen-agers and seniors, Kuhn said.

Five hundred people are expected to attend the event, which will begin at 6:30 p.m. at the Alicante Princess Hotel in Garden Grove. “Max is so loved by so many different segments of the community that people have really been coming out of the woodwork to participate in this effort,” Kuhn said.

He was the first person I ever heard speak about gay and lesbian people as if they were absolutely normal, competent and part of their total community . . . . He certainly did help me as I go about my work in Orange County as an openly gay elected official.

--Bob Gentry,

Laguna Beach city councilman

While Schneider’s friends laud him as a human-rights advocate and a role model for homosexuals in the professions, his colleagues view him as a pioneer in alcohol and drug abuse research, treatment and prevention. Over the past 30 years, he has championed medical treatment for addicts and for physicians who abuse drugs and alcohol, and he has pushed for classes in alcoholism to be made part of the medical school curriculum.

Schneider, who retired from private practice in 1980, now teaches at the UCI medical school, serves as educational consultant to the Family Alcohol and Drug Recovery Services of St. Joseph Hospital in Orange, and makes and distributes educational films through his own company. He is also the outgoing president of the American Medical Society on Alcoholism and Other Drug Dependencies and is a member of the board of directors of the National Council on Alcoholism. This year he is president of Southern California Physicians for Human Rights.

This month, he was presented with the Vernelle Fox award by the California Society for the Treatment of Alcoholism and Other Drug Dependencies for his advocacy, enthusiasm and statesmanship.

Internal Organs Affected

Schneider said he was drawn to addiction prevention when he saw the effects of alcohol and drugs on internal organs when he was practicing as a gastroenterologist in Buffalo, N.Y.

He moved to Orange County in 1964 and, his colleagues say, became one of a handful of doctors then treating alcoholism as a disease.

Alcoholics “are hard to take care of,” van den Noort says. “You get them all patched up, and they go out and drink some more and come back with another set of problems. Max is one of those doctors who ends up with patients nobody else wants to take care of. . . . It’s a measure of a good doctor when the difficult patients hang in there with him.”

Schneider is concerned that addictions are treated separately in Orange County. For instance, alcoholism is the concern of the Health Care Agency’s Alcoholism Services division and drug abuse is overseen by the agency’s Mental Health and Drug Abuse Services division. “Give me a narcoticaddict, and I’ll give you an alcoholic once he gets off the drugs,” Schneider says. Most young addicts today are addicted to more than one substance, he said.

He believes there are not enough services available to the indigent addict nor enough in-patient programs for low-income patients under 18 or over 65.

Since lesbians and gays have an unusually high incidence of alcoholism or substance abuse, his contribution in the field is very significant.

--The Rev. Rodger Harrison,

Founder and former pastor of Christ Chapel, Metropolitan Community Church, Santa Ana

Schneider has lectured widely on the relationship of alcohol and drug use to AIDS. “There’s good evidence to show that all these drugs, and especially alcohol, may impair the immune system,” thereby increasing the risk of AIDS for homosexual alcoholic men, he said. Moreover, those under the influence of drugs or alcohol are more likely to indulge in unsafe sexual practices because their judgment is clouded, he said.

26 Friends Died

In Schneider’s small, worn address book, a list of 26 names fills a page. They are the names of friends who have died of AIDS. Three were doctors.

AIDS has robbed the homosexual community of its sensuality and much of its creativity, he said. “We had a sexual freedom--if it feels good, do it,” he said. “It may feel good, but the price is costly.”

Many doctors in Orange County know him from his days in Buffalo as having been his students. At that time, he was perhaps not as openly gay as people are today. He developed a support network not for just gay and lesbian doctors but others as an alternative to the bars.

--Werner Kuhn

Director, Gay and Lesbian Community Services Center of Orange County

Max Schneider knew he wanted to be a doctor when he was 7. There was a fire in his neighborhood, and he used his first aid kit to patch a firefighter’s finger. He also knew at 7 he was homosexual but tried to hide that fact, he said, by over-achievement in traditional male activities: wrestling, boxing, football. As a student at the University of Buffalo School of Medicine, he tried to change. He dated women but found it “unfulfilling.”

He thought about seeking a psychiatrist’s advice but believed that anyone he consulted would arrange to have him thrown out of medical school. “In retrospect, I was probably 100% correct,” he said.

After much introspection, he concluded that the single most important quality for a doctor is integrity. After deciding that, he accepted himself for what he was, he said.

The sexual orientation of a patient’s doctor is not the patient’s business, he believes. But, he said, he feels sorry for doctors who choose not to reveal their homosexuality. “They are probably excellent physicians but miserable and unhappy people.”

His homosexuality was rarely an issue in his practice--a successful one that catered to the mainstream community, Schneider said. Once he was excluded from a group practice, but, he said, “I was never quite sure whether it was because I was Jewish or gay. Or gay and Jewish.”

He did not tell his parents until he was 35 and a clinical instructor in medicine at the University of Buffalo School of Medicine. “They were totally accepting. My mother said, ‘Why didn’t you tell us before?’ ”

“I said, ‘I didn’t want you to think I was going with a non-Jewish boy,’ ” he said. “They failed to see the humor.”

He’s a marvelous, warm, witty individual.

--David Larson,

Executive director, National Council

on Alcoholism, Orange County

Dr. Daniel Ninburg, an Anaheim family practitioner and former student of Schneider’s, recalled his classroom introduction to him. “He walked down the aisle, turned around to face the audience and said, ‘My name is Max Schneider and I’m a nut!’

“Two minutes after that introduction, he asked one of the students to examine his cut finger. Suddenly Max disappeared and was on the floor. It was his graphic way of teaching a lesson: You don’t examine a patient with the patient standing up. Anyone with a cut might faint.”

When he is to give a speech and the introduction goes on too long, Schneider has been known to lie down in front of the podium feigning sleep or emit a loud stage yawn. He plays Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny at local hospitals.

In Buffalo, Schneider was the official doctor for firefighters and police officers. When he was late for a lecture, he thought nothing of snapping the magnetic red light on the roof of his station wagon and turning on the siren. “For that reason alone, they were glad to see me leave,” he said.

Not everyone has loved his sense of humor. When women complained 10 years ago that his lectures and jokes were sometimes offensive, he dropped sexist, smutty and ethnic jokes from his talks, he said. He knows how subtle discrimination feels. Sometimes when someone tells a homosexual joke, he’ll wait until the speaker is finished to ask: “Do you know anyone who is homosexual? Well, you’ve just met one.”

The beautiful part about it is he and his lover have his mother living with them. She said she’d rather be here with her son, his lover and their nice friends than in an old folks home in Buffalo.

--Frank Newman

When Schneider and Ron Smelt, 37, a former psychiatric technician, decided to have a committed relationship, Smelt moved in with Schneider and his mother in their north Orange County home. That was 16 years ago. It took five years to adjust to his new family life, Smelt said. But he persevered because he wanted the relationship to succeed.

Most of their friends are homosexual couples in committed relationships, he said. Many of them do not understand why Schneider and Smelt accept most mainstream social invitations as a couple. “We feel strongly our life can be an example,” Schneider said.

They belong to two Jewish temples and one fundamentalist church and believe in a higher power, “whatever color She may be.”

When our church was burned by an arsonist, he was there the next Sunday and made a significant contribution. It helped it survive.

--Rodger Harrison

Ten percent of his income goes to a long list of charities, ranging from the temples and churches and alcoholism prevention programs to the Elections Committee of the County of Orange, county arts institutions and Native American Indian groups, Schneider said. He also lends money to gay students, some of whom are from affluent families who disowned them when they learned of their homosexuality.

The library at the Gay and Lesbian Community Services Center is named for him and Smelt. The annual Southern California Physicians for Human Righs scholarship is called the Max Schneider, M.D. Honorary Scholarship fund, and proceeds from the roast will start the Max Schneider Endowment Fund.

Max himself has had a chronic illness for a long time. Myasthenia gravis is a disease which . . . causes weakness in face and voice and sometimes breathing, sometimes arms and legs. It’s . . . similar to rheumatoid arthritis and unrelated to AIDS. It’s not easy to treat or to live with . . . but he has maintained this remarkably active program in so many ways.

--Dr. Stanley van den Noort

When it became obvious that he was sicker than many of his patients, Schneider took a colleague’s advice and retired.

“The way you live the longest is to get a chronic disease and take care of it. Or: When natures gives you a lemon, you make lemonade.”

Some people think he’s a “hard-hearted SOB,” he said. In fact, he cries at parades, is so shy he can’t make small talk, becomes uncomfortable in crowds and still feels the pain of anti-homosexual insults, he said.

Schneider said he sometimes wishes he had been born into the mainstream rather than into the merry-go-round of guilt and coping associated with homosexuality.

But then a new thought came to him. “Without the painful stimulus to help me grow,” he said brightly, “look how mediocre I would have turned out.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.