‘I’m More at Peace Now’ : Vermont Inn Is Haven and Home to Economist

- Share via

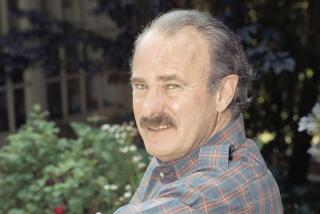

CHESTER, Vt. — Running an inn in a tiny Vermont town seems an unlikely occupation for a nationally prominent labor economist and former college president--that is, until the innkeeper turns out to be John R. Coleman.

Coleman has a penchant for turning up in unlikely places. That was him in ‘73, digging sewer ditches in the early morning chill of an unseasonable Atlanta spring, and, later, hauling garbage in a Washington suburb.

Unlike his fellow laborers, however, Coleman climbed out of the ditch to chair a meeting of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia. He quit his job with the garbage crew to resume work as president of Haverford College.

“There’s a restlessness in me, a desire to walk in other people’s shoes,” says Coleman, whose adventures as an anonymous laborer became the subject of “Blue-Collar Journal: A College President’s Sabbatical,” one of seven books he has written. The others, including one co-authored by Secretary of State George P. Shultz, concern labor economics.

Coleman’s latest bout of restlessness, in January of 1986, led him to Chester, a southern Vermont town of 3,000 people, white clapboard houses and leafy maples, where horses graze on Main Street and folks greet each other by name.

“My hobbies are listening to music and cooking. I mentioned this to a friend who said, ‘Oh, you’re talking about an inn.’ I thought about it for a couple of years before I dared to say it out loud,” Coleman says.

With the help of his son and daughter-in-law, he renovated the vacant three-story Chester Inn, transforming it into an airy Victorian showplace that opened for business the next May.

Coleman called it “The Inn at Long Last,” a name that alludes to the new-found contentment that has accompanied his move to Vermont.

“I’m more at peace now,” says Coleman. Indeed, he looks right at home perched on a tufted leather Chesterfield in the lobby, a spacious room with a high ceiling, a fieldstone fireplace, handmade quilts and venerable antiques.

“Very few people come to an inn by mistake,” he says. “In a year, only one man didn’t like it. He wrote a letter complaining that we had ‘old’ furniture, that there were no phones or TV sets in the rooms.”

Though he lives in an apartment next door, Coleman considers his customers guests in his home. With each of the 37 guest rooms named and decorated for people and places that are special to him, a stroll through the inn becomes a journey through the innkeeper’s past.

The Old Boston Room recalls Coleman’s days as a professor at MIT, as well as his job as an anonymous salad-and-sandwich chef at the Union Oyster House, a popular Boston eatery.

The Copper Cliff Room is a recreation of his boyhood home in a Canada mining town, “a place grim and barren to visitors, but a place of pride and accomplishment to us.”

The Kathleen Ferrier Room is a sentimental tribute to the beautiful young singer who captured Coleman’s imagination during a concert in London in 1944. The inn’s collection of her recordings is often shared with guests.

“Taking over redecorating an old inn is like playing house for keeps,” says a written introduction to the inn. “The imagination gets free reign. Each room can become just about anything the players want it to be. . . . “

What Coleman wants his inn to be, for his guests and himself, is a haven as well as a home. But that isn’t to say that his search is over.

Fifteen years ago, Coleman’s three-month leave from Haverford, a small liberal arts college in Pennsylvania, enabled him to return to the blue-collar work of his youth, when he toiled as a 39-cent-an-hour smelter in his Ontario hometown, the center of the world’s nickel industry.

“Ever since I was very young, I’ve been interested in what others do with their lives,” says Coleman, a 65-year-old grandfather, whose elfin features and reedy slimness belie the hard labor he’s done.

“My mother was friends with everyone, unless they put on airs. She was the same with the mayor, the garbage man, the man who brought the eggs. She cared about all of those people.”

Like mother, like son. Coleman’s fascination with the world’s laborers never left him, not even as he joined the ranks of the world’s managers.

As a professor and college president, Coleman had often urged his students to take time out to vary the rhythm of their lives.

During the early ‘70s, when Coleman perceived a growing rift between academia and the workaday world, he decided to take his own advice.

Those first three months merely whetted his appetite. The following summer, Coleman once again abandoned the ivory tower for the back of a garbage truck, resuming a job that made him feel at once “happy and proud.”

He followed it with stints as a roughneck on a drilling rig in the uranium fields of New Mexico, a miner in a marble quarry in Wyoming, and a construction worker at a sewage disposal plant in New Jersey.

He left Haverford in ’77. “I had announced my impending resignation during the winter, and in mid-March, I fell asleep in class. I was right in the middle of a sentence,” he recalls. “That was the end of my career.”

On to New York City, where Coleman became president of the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, a philanthropy devoted to the severely needy. The job kept him busy, but not too busy to take to the streets for 10 days in January of 1983 to live the life of a homeless man.

Dignity Is His Theme

Two nights a week, he donned the uniform of the city’s auxiliary police and patrolled the streets of Manhattan. He also served as an emergency medical technician, and is thinking of joining a voluntary ambulance crew in Vermont.

He takes time out from innkeeping to speak to local groups about his experiences. The theme is always the same: dignity.

“I have matured in my understanding of the concept of the dignity of every person, the fundamental worth of every person,” he says.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.