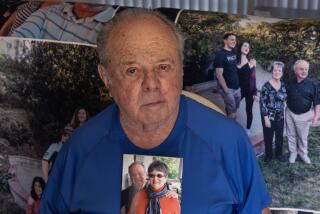

Demands Ban on Lawn Darts : Daughter’s Death Spurs a Father’s Sad Crusade

- Share via

David Snow didn’t even want lawn darts when he went shopping last April. He wanted a volleyball set, but all the department store had was volleyball in a combo pack with two other games. Fine. He took it. The darts would stay in the box.

Then one Sunday, Snow’s 9-year-old son, Paul, and some other children in the family’s attractive Riverside neighborhood took the slender, metal-tipped, one-pound darts out of the garage and began playing with them in the back yard, trying to lob them into plastic rings on the ground.

One of the children threw one too high and too far. It sailed over the fence and came down in the front yard, where Snow’s other child, Michelle, 7, was playing with her doll. With a force one researcher estimated at 23,000 pounds per cubic inch, the dart penetrated her skull. Within minutes she collapsed. Three days later doctors pronounced her clinically dead.

Like many anguished parents before him, Snow looked for a way to make sense of the tragedy. “I promised her that the toy that took her life would never take another,” he said. “She knows that Dad always kept his promises.”

Such vows all too often crumble under the weight of prolonged grief. But today, less than six months since his daughter died, David Snow stands on the brink of single-handedly conquering the lawn dart. On Thursday, the three-member federal Consumer Product Safety Commission will meet in Washington to consider banning the product.

The speed with which the commission has moved on the issue is regarded with astonishment by consumer activists and government staff members familiar with the regulatory agency’s snail-like pace.

Equally remarkable, these observers say, is how effectively Snow--a 39-year-old aerospace production supervisor who had never been to Washington or even written a letter to a congressman until he began his crusade--turned himself into a well-organized, emotionally powerful one-man lobbying machine.

One speech made the biggest difference. Eight weeks after Michelle died, Snow delivered 20 minutes of searing testimony to a House of Representatives subcommittee, condemning the commission for failing to enforce regulations intended to keep lawn darts out of the hands of children. Within days, the commission began an investigation of lawn darts that substantiated Snow’s claims.

“I’ve been in a lot of hearings and I’ve never seen anybody make that kind of impression,” one House aide said. “You could have heard a pin drop.”

The dispute over lawn darts is a small speck in the recreation industry, compared to controversies such as all-terrain vehicles, which have been blamed for hundreds of deaths. But despite his narrow focus, Snow inadvertently became a player in a larger story: the mounting criticism of the Consumer Product Safety Commission under its chairman, Terrence M. Scanlon, who has argued that the commission should seek voluntary compliance from manufacturers of potentially unsafe products rather than turn to enforcement actions that might economically injure businesses.

Last month, as Snow’s campaign gained strength, Scanlon stripped the agency’s longtime chief of compliance--who favors a ban on lawn darts--of much of his authority. That reassignment, in turn, provoked congressional calls for Scanlon to resign. It also led, on Friday, to the introduction of legislation to weaken the commission’s reliance on voluntary compliance and require it to more quickly crack down on potentially unsafe products.

Thanked by Congressmen

At a press conference in Washington, the bill’s co-authors, Rep. James J. Florio (D-N.J.) and Rep. Dennis E. Eckart (D-Ohio), thanked Snow for motivating them.

All of which is fine, David Snow allowed, but right now the only thing in the world that matters is finding a way to pull lawn darts off store shelves. Now.

“I want to get these damned darts,” he said slowly. “These things killed my child. If I don’t do anything, it’s just a matter of time before someone else gets killed. I’m trying to save lives . I’m going to get them off the market. Whatever it takes.”

With grim single-mindedness, Snow has spent hundreds of dollars a month on phone calls and has written scores of long, perfectly typed letters to public officials, placing a photograph of Michelle, a pretty, dark-haired girl, at the top of each one.

The letters, like their author, are a penetrating combination of reason and anger. “I will crawl over, under, around or through you and your agency,” one warned Scanlon.

For weeks after Michelle died, Snow and his wife, Linda, were frozen. Snow tried going back to work at Hughes Aircraft after two weeks. He couldn’t.

“I’m in a meeting, and these guys are talking about a parts shortage like it’s the end of the world. People say, ‘Hang in there. You’ll get over it.’ You never get over it.”

Gradually he began to make inquiries about lawn darts. His first discovery shocked him: For 17 years, the federal government had had rules on the books aimed at preventing children from using the darts.

In 1970, three years before the Product Safety Commission was created, the Food and Drug Administration flatly banned the lawn dart, citing three deaths and numerous injuries to children. Distributors challenged the ban in court and won a compromise.

Under the compromise regulation, lawn darts could be marketed only as a game of skill for adults. A hazardous-to-children warning had to be put on each package. In addition, they could not be sold in toy stores or toy departments.

There was a warning on the three-foot-tall combo package Snow bought in a neighborhood department store. He is still haunted, he said, by the fact that he never saw it. It was small, less than 2 by 4 inches in size, written in lettering that was extremely thin but whose height met the required one-fourth-inch type standard. Nor was the product segregated from toys. “I was with Michelle, and I could touch the Barbie dolls with one hand and lawn darts with the other.

“I felt I’d been duped,” he said.

In May, after Snow had begun writing letters to congressmen but getting nowhere, an voice cracked as he displayed a picture of his daughter and pleaded with the commission for tougher enforcement.

“What he had done--which amazed me because he was still in shock and very fuzzy--was to take this tragedy out of the first person and put it into the third person, to detach himself,” said Signy Ellerton, administrative assistant to Snow’s congressman, Rep. Al McCandless (R-Bermuda Dunes).

“He forced people to take a look at how the agency has misused the voluntary-standards concept in deference to hazardous products,” said Susan Weiss, a lobbyist for the Consumer Federation of America, which advocates a lawn-dart ban.

Orders Staff Investigation

The commission, already under attack for failing to aggressively regulate criticized products such as all-terrain vehicles, swimming pool covers and disposable cigarette lighters, responded by ordering a staff investigation of lawn darts.

For the first time, the commission’s injury clearinghouse, which makes national estimates based on reports from about 70 hospital emergency rooms, separated lawn dart injuries from all dart-related injuries.

It turned out that David Snow was right about 22 injuries being a conservative estimate. Between 1978 and 1986, the new check showed, the number of people treated at hospital emergency rooms for lawn dart injuries was about 6,100.

Of the victims, 81% were 15 or younger and half were 10 or younger. More than half were injured in the head, eye, ear or face, and many cases involved permanent injury. (There were no deaths during the nine-year period. Michelle’s was the first death since 1970.)

Labeling and marketing violations were routine.

The commission collected 21 models of lawn darts from 13 importers and one domestic manufacturer and found that all failed to comply with warning requirements. Ten of the models lacked the required front-panel warning.

The commission also surveyed 53 retail stores and found that one-third of them were displaying lawn darts with toys or with sporting goods that were obviously intended for children.

The findings underscored the frequency with which an ostensibly adult game winds up in the hands of children.

“Who are we trying to kid?” Snow asked in an interview. “I don’t care where they sell them, what they put on them. Children will use them. You can see where ‘voluntary compliance’ gets you.”

Dr. Joseph Greensher, a spokesman for the American Academy of Pediatrics, said his organization has lobbied against all projectile-type toys. “Invariably what happens is they get thrown up in the air, then they come down like a missile,” he said.

The debate makes industry groups uneasy. A spokeswoman for the Toy Manufacturers of America declined comment, noting that lawn darts must legally be sold as sporting goods. A spokesman for the National Sporting Goods Assn. declined comment, contending that “lawn darts fall more into the ‘toy’ category.” A spokesman for Oshman’s Sporting Goods said the chain “recently” stopped carrying lawn darts out of fears that “there might be an unusual (liability) exposure,” but insisted that Michelle Snow’s death had nothing to do with the decision.

David Snow’s life, already a blur, began moving even faster after the commission’s study was released in late June. The commission called a meeting of lawn dart distributors in July and won agreement for improved labeling and retail sales practices--but only on the condition that they not take effect until 1988 or 1989. Two weeks later, the commission published a new safety warning on lawn darts.

That was not enough for the commission’s critics. In early August, Rep. Florio, chairman of the House commerce subcommittee that oversees the commission, accused commission Chairman Scanlon of turning the agency “into a complete wimp.”

In late August, Scanlon further outraged his critics by reassigning David Schmeltzer, the agency’s head of compliance, to a special project. Scanlon described the transfer as a temporary response to “serious management problems.”

Sources familiar with the reassignment suggested that the lawn-dart issue represented a final straw in a continuing dispute between Scanlon and Schmeltzer over the wisdom of letting voluntary action by industry settle product safety disputes.

Commissioners Objected

The two other members of the commission objected vehemently to Schmeltzer’s reassignment. One of them, Anne Graham, accused Scanlon of trying at “every opportunity” to “undermine” the commission’s enforcement arm. Earlier this year, Graham and Commissioner Carol Dawson accused Scanlon of attempting to undercut the agency’s proposed recall of all-terrain vehicles, which have been labeled unsafe by the agency.

Schmeltzer said in an interview that he did not know precisely why Scanlon had reassigned him but said he believed that the agency should ban the lawn dart.

“My main objection is that if you give it to a 10-year-old, he’s going to pick it up and wing it, not play with it like they say,” Schmeltzer said.

Two weeks ago, the commission received a briefing from its staff on the wisdom of banning the lawn dart. Various departments of the agency were split, with some advocating continued voluntary restrictions. Working the telephone from his home, Snow tried to soak up the nuances, but he grew frustrated. He was not sure what was going to happen.

He decided last week to fly back to Washington before the commission made its decision.

“I’m going to raise some hell,” he said. “I only need two of the three votes to get a ban. I’m going to do my best to straighten them out.”

By now his clout was established. He landed in Washington on Monday. On Tuesday, a local television station’s consumer reporter interviewed him. Later in the day, thanks to help from his congressman, he met with representatives of President Reagan’s assistant for consumer affairs. The next day, he met with each of the three consumer product safety commissioners. By the time he was finished he felt that he had two votes--Graham and Dawson--on his side.

Other observers of the commission said it was just as likely that Dawson would seek softer curbs. “She hates the word ban; it’s hard for her as a Republican to do that,” said one. But for the moment, Snow felt that he was winning.

“I got a good feeling,” he said as he prepared to fly home.

It was a far cry from June, when he had confessed to a newspaper reporter: “I don’t even know how to get things done. I doubt if these letters are even going to be read.”

It was closer to a moment he had hoped for so desperately, a moment when he could put his crusade behind him and stop confronting his life’s worst memory at every sentence.

“I want this to be over,” he said, his sad eyes looking more weary because of a cold. “Once I pick up a paper and see that they’re banned, I’m going to crawl back under a rock and never talk about lawn darts again.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.