Jilted by His Fairy Godmother : OUT OF THE WHIRLPOOL<i> by Alan Sillitoe; illustrated by Peter Farmer (Harper & Row: $10.95; 123 pp.)</i>

- Share via

Alan Sillitoe’s favored theme, since his debut in 1958 with “Saturday Night and Sunday Morning,” has always been the quest of a disadvantaged hero for the magical key to a better life. In “Out of the Whirlpool,” a new short novel, he offers an unsparing reconsideration of the terrors and delights of the poor boy suddenly become lucky. In the process, Sillitoe revisits his own roots--in 1950s Nottingham, England.

Nottingham is also the home territory of D. H. Lawrence. And in fact, “Out of the Whirlpool” resembles a minimalist replay of “Lady Chatterley’s Lover,” with the conclusion gone sour. Instead of the romantic gamekeeper, we have Peter Granby, unskilled laborer in a furniture factory, age 19; and in place of the aristocratic lady of the woods, we have Eileen Farnsfield, the handsome, 40-ish widow of a suburban architect, who befriends Peter and hires him as caretaker.

It’s a match made somewhere other than in heaven, yet for a while, the precarious balance in the relationship works. He gets a rewarding sexual partner, and wider experience of the world. She finds herself recovering a taste for life, enjoying Peter’s sweet looks and open sexuality.

Since Peter’s family seemed to have had no resources for nurturance beyond the bare survival level, and his mother died of cancer while he was in his early teens, the age difference suits him fine. In his imagination of happy endings, the fairy godmother makes the perfect bride. But Eileen knows better: She hasn’t the maternal temperament, and besides, she’s not about to make herself look ridiculous in the eyes of her upper-class friends. For her, caste rules apply.

The crisis between them, when it comes, is a sharp, violent battle whose outcome seems inevitable from the start. Yet there is renewed hope at the end in an alliance with a young West Indian woman. It may be the immigrants who will help resolve the ingrown class-conflicts.

Sillitoe has great sureness of touch with his environment here, even in passing glances at the decaying industrial landscape: “A pebble dash of ice and snow covered the old lime kilns near the canal, bricks scattered like pieces of thrown-away cake. You could see where the oven doors had been.” He knows all the dog breeds of his neighborhoods, and he knows exactly what passes for haute cuisine in Eileen’s suburb (wine with the pot roast, cream on the dessert).

This highly specified vision is paired with a real compassion for the young victims of the urban underclass. They are, Sillitoe sees, victims not just of exclusion from mainstream benefits but also of the careless incompetence of their own brutalized elders. Bad fathering is not excused by circumstances. Nor are long-suffering women let off: They won’t think or plan; they are selfishly content with trivial pleasures.

You feel, reading, that Sillitoe has earned a right to the anger that smolders here. But “Out of the Whirlpool” might have been a stronger work if the targets of his indignation were challenged more abrasively.

In substance, the book explores a gentle adolescent’s furnishing of his heart and soul. On the other hand, its style, which is often graceless, denuded to the point of mutilation, reveals a profound disgust with the realities that are handled. The result is an impression of conflicting rather than complex purposes.

Peter Farmer’s line illustrations capture the wispy appeal of the young hero, as well as the grotesqueness of his elders.

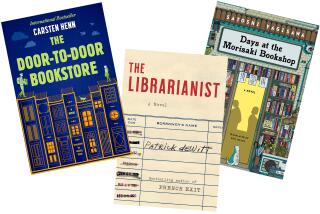

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.