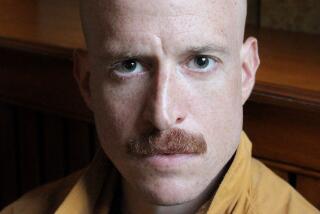

More Cannibals in Manhattan : HE GOT HUNGRY AND FORGOT HIS MANNERS <i> by Jimmy Breslin (Ticknor & Fields: $14.95; 275 pp.) </i>

- Share via

If New York has become the Emerald City for the young, the educated and the acquisitive, then the city in Jimmy Breslin’s new novel, “He Got Hungry and Forgot His Manners,” is the dark netherworld that seethes beneath the glitter.

This is the other New York--of welfare mothers watching “Santa Barbara” and “Hawaii Five-0” in the rat-infested Flatbush Arms Hotel, and of prim tycoonesses who patronize good causes. It’s the city of black and white, Howard Beach; of white teen-agers armed with Louisville Sluggers and gangsters who lead normal lives while spilling abnormal amounts of blood.

Into this nightmare city come two strangers from a strange land, Father D’Arcy Cosgrove, an Irish missionary who has spent years in Africa preaching the evils of sex, and Great Big, a seven-foot Yoruba with an enormous appetite--occasionally for people. By an intentional mistake, they are assigned to an impoverished Brooklyn parish, across the marshes from Howard Beach.

As Cosgrove struggles to desex the natives there, he finds himself sucked ineluctably into the welfare system in order to survive. Along with the super-promiscuous Disco Girl, whose purpose in life is having a steady supply of babies to ensure a steady flow of welfare, and Baby Rock, a nice homeboy with savage proclivities, the priest sets out to bring what Breslin calls “the largest single industry in the greatest city on earth”--welfare--to a standstill.

Despite all the uncaring clerks, computers and bureaucrats that victimize them, it remains difficult to feel complete sympathy for these characters. They’ll take whatever they can get and have relinquished responsibility for their own lives. They are welfare junkies.

Some have been thwarted by the other realms of the System--the educational system, for example. But whenever was life without obstacles, whatever your socio-economic status? Social realism here consists of plenty of crack vials and an overblown ghetto dialect that uses countless “be’s,” as in “we be goin’ to the welfare office.”

To make the fable complete, above and beyond them--and controlling their fates--are the wealthy women patrons of the New Opportunity Partnership, who work hand in glove with the major developers, who, in their own way, are said to dine on human flesh.

So we get a richly ironic view of the self-sustaining poison of welfare. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to discern a clear position here vis a vis the evil itself. We get a sharp passage on “the Son Business” in New York, which is another pet Breslin industry--the one in which the sons of successful men seem inevitably to become big wheels in the same business. But beyond that, we’re left with metaphor.

Like the cannibal who forgets his manners when he gets hungry enough, the voracious men who build and run New York City are eating the rest of us alive. Or something like that.

After the sustained narrative success of “Table Money,” his last novel, Breslin has kicked back into the fabulist mode, cooking up a tale of hunger and heartbreak, cannibals and missionaries that tickles the palate. But we be wanting more.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.