THEATER REVIEW : ‘Freud’ Affords Scant Insight Into the Man

- Share via

SAN DIEGO — The pleasure inherent in a one-person show on the life of Sigmund Freud is the prospect of listening to one of the great people of history.

Similarly, the problem inherent in a one-person show is the prospect of listening to one of the great people of history. How many people are that interesting when delivering monologues for 90 minutes to two hours?

“Freud,” which plays through Sunday at the Hahn Cosmopolitan Theatre, deals with the dilemma by presenting a warm and witty professor with a wonderful sense of humor.

Somehow, it’s an approach that works better with Will Rogers, portrayed by James Whitmore in a one-man show, than with the controversial father of psychoanalysis.

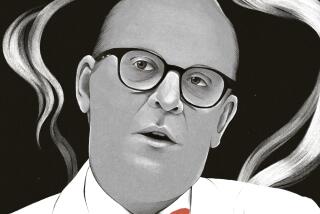

Despite an impeccably professional performance by Harold Gould in the title role, Lynn Roth’s script gives broad strokes rather than insights into the personality of the man. It’s as if every time she had a choice, she elected to bring the jokes rather than the man to life.

Did you know that Freud had a fear of traveling? We get to laugh at him counting his two pieces of luggage over and over to calm down, but we never find out why he is so afraid. Did you know that he spent a lot of time with his sister-in-law, with whom he may have been in love? He brings up the subject early and drops it, making the most glancing of references later on to the fact that his obsession with work cut out physical intimacy with his wife.

Ironically, while Roth has Freud rage about his theories being watered down by his former disciples, she offers nothing if not watered-down versions of those theories.

Sure he exclaims that his concern with the sexual roots of neurosis is part of what makes him a social pariah. But the script quickly glosses over those sexual references as if afraid of offending even today’s audience.

What about Freud’s views on religion, the Oedipal theory, religion, the id/ego/superego and women?

In an effort to make Freud palatable to the masses, Roth deprives us of the uncompromising thoughts that made him so dangerous to his colleagues and the society in which he lived.

Lenore DeKoven’s direction keeps the two hours moving at a comfortable trot. The uncredited set is a comfortably appointed study that annoys by bringing up a lot of details--an African figurine and various mementos--that are never explored. The lighting follows Gould’s movements with self-conscious abruptness.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.