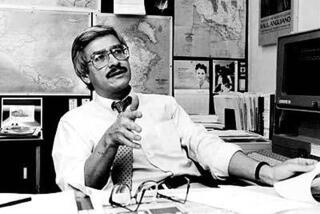

Agustin De Mello Calls ‘Whiz Kid’ Son His Greatest Creation; Some Say That’s Precisely the Problem

- Share via

SANTA CRUZ, Calif. — Unshaven and disheveled, Agustin Eastwood De Mello sat slumped on a kitchen chair beside his shattered rear door, waiting for a call from his son.

Two days earlier, around 6 in the morning, eight Santa Cruz police officers in flak jackets had kicked in the door and charged into the kitchen.

De Mello was strapped to a gurney and taken by ambulance to the local psychiatric ward for observation.

Eleven-year old Adragon, the celebrated “whiz kid” who graduated in June from UC Santa Cruz with a degree in mathematics, was placed in protective custody, the tail on his hamster pajamas flopping as he walked out the door.

Heads the Local News

Here in Northern California, the De Mello story leads the headlines and broadcasts. Yet, despite the details of each new twist--the police seizure of 10 guns, videotapes and Adragon’s physics, astronomy and math assignments; De Mello’s release from the psych ward, and his subsequent arrest on felony child endangerment charges; last Thursday’s hearing, postponed till this week, to determine where Adragon should live--the De Mello story remains largely a mystery.

To many of De Mello’s supporters, it’s an absurdist drama about an extraordinarily close and extraordinarily intelligent father and son doomed to suffer the intolerance of a pathetically ordinary culture.

To the police and others, it’s a potential horror story about the gourmet baby trend turned pathological, a story in which authorities headed off an unstable Svengali before he could destroy himself, or the people he thinks impeded his son’s rush to intellectual glory, or the mother who is fighting for custody of the child, or the boy he believes may well be “the most intelligent child so far found in this world.”

And in this quintessentially mellow Northern California refuge, where people pride themselves on being smart enough to have fled the fast lane to luxuriate in life, the De Mello battle is also about the definition of happiness.

Until last week, the one person whose life seemed an open book was Adragon (“A.D.” to his friends). Cameras were there when he entered Cabrillo junior college at age 8, when he graduated with highest honors at 10, when he condensed the last two years of university classes into one to become the youngest university graduate in American history, and when his father announced that the boy, whose stated goal is to win a Nobel prize by 16, might have to go to the Soviet Union because American universities were unwilling to accept him into a graduate program.

But now Adragon (so-named because he was born in the Chinese year of the dragon) is being held incommunicado by Santa Cruz Child Protective Services, and the agency “will make absolutely no comment” on the case.

Cathy Gunn, Adragon’s 36-year old mother, is far less visible. A Silicon Valley technical writer, she is known publicly only by what she said to a police investigator, as reported in the thick affidavit filed to justify the search warrant for De Mello’s house. In that, she told investigators that her son believed De Mello was “losing it,” that the boy and his father had made a “suicide pact,” and that De Mello had made a thinly veiled threat of violence.

When she spoke to The Times on Friday in an exclusive interview, she remained extremely cautious, opting not to fill in many of the holes that riddle the public’s picture of the estranged family’s past.

But it is Agustin De Mello who remains the most elusive in the family. Never reluctant to tell the media that his son at 7 weeks looked up and said “hello,” that the boy as an infant pondered the model solar system hung above his crib, or that Adragon at age 3 expressed the scientific theory “electric chemicals make boys,” the self-described genius and anarchist is also quick to deny all of Gunn’s accusations. Yet he is irritated by questions concerning his own life.

“All documents relating to my early background are not correct,” he said when told that records show he was born in Massachusetts in 1929. “I can’t go into it more than that. . . .”

The threads of De Mello’s life that do reveal themselves can be woven into an offbeat drama, in which the hero careens through life, dog sledding on the Hudson Bay, breaking bricks on a Johnny Carson show, penning romantic poems about immortality, and wailing through New York’s Greenwich Village on a motorcycle with hipster Wavy Gravy hanging on behind.

Certain motifs resonate in the way Agustin and his son lived. In the cluttered pink frame house that De Mello rents from his next-door neighbor, the living room, whose curtains are almost always drawn now, is strewn with leaning towers of physics books, a wading pool that housed Adragon’s two box turtles (impounded by the SPCA after the search), a telescope and a baby grand piano heaped with litter, and a bust of Beethoven.

The walls display paintings of castles, and at least five pictures of Albert Einstein. One bears the caption: “Great spirits have always encountered violent opposition from mediocre minds.” At least two photos of Clint Eastwood, whom De Mello says is a distant relative, hang over a dusty collection of his wrestling, judo, and shooting trophies on the mantle.

But it is Adragon, his pretty face framed by a Prince Valiant haircut, whose photo appears most frequently on the walls.

Soon after the boy entered Cabrillo College, the media were drawn to his remarkable feats. But soon some reporters began looking askance at the unusual bond between the two. In January of ‘87, the San Jose Mercury News began discussing “the debate” about just how brilliant Adragon really is. Last fall “60 Minutes” drew attention to Agustin’s hazy past and, De Mello said, “insinuated that Adragon was a victim of me.”

Pushed Beyond Capabilities

Some of Adragon’s teachers, including the director of a Santa Cruz school for gifted children, believe Agustin pushes the boy far beyond his capabilities. One of the charges under investigation by the Santa Cruz district attorney is Gunn’s allegation that she and De Mello did so much of Adragon’s work for him that a fraud has been perpetrated against the university.

De Mello’s supporters, including several of Adragon’s professors, say that while Agustin did indeed hover over his son’s academic career, coaching, cajoling, and intervening whenever someone seemed to lack appreciation for the boy’s genius, there is no question that Adragon earned his degrees.

More than anything else, including the threat of criminal prosecution, the charge that Adragon may not be a prodigy seems to upset De Mello most. “It’s criminal,” he said, for Gunn to have suggested that perhaps the boy should return to junior high school, rather than attend graduate school as planned.

De Mello gazes out the window of a restaurant on the Santa Cruz wharf, toward his house visible across the bay in the pink light of sunset. Tears run down his face.

He is trying to describe his new nightly ritual of going into his son’s empty room to say good night to the blue teddy bear he bought when Adragon “was still in the gestational stage.” But he can’t make it through the sentence.

“Me being all weepy-eyed. It’s nothing compared to what he must be going through,” De Mello says of his boy, with whom he has still not communicated. “When you’re this close to a child you can feel the pain.”

“My own feeling is that I’ll never see or hear from my son again,” he says. “I’ve given it tremendous, tremendous thought. I don’t see any happy ending here. I can’t see a happy ending. . . . I know it sounds terrible, but I feel Adragon may have been destroyed, emotionally and mentally, beyond repair. . . . This is my greatest fear, worse than the fear of death--of being burned alive or drowning. . . .

“Nothing I’ve done creatively can compare to creating my son. Nothing comes close. So, as far as accusations about a suicide pact: Ridiculous. I don’t know of anyone who would destroy their greatest creation.”

Repeatedly, De Mello refuses to talk about himself. “What I’ve done means nothing whatsoever. . . . What little time I have left I want to focus on memories of my son.”

Gradually, though, he begins to let a few more “pieces of the puzzle” slip out, revealing obvious patterns in his symbiotic--some would say obsessive--relationship with his son.

Lived With Grandparents

His parents separated when he was very young, and he lived with his grandparents for a time “on the East Coast,” he said.

“I have fond reflections of my grandfather teaching me when I was very young, those are my happiest memories,” he said. But in first grade, he said, he began to doubt the efficacy of the American educational system in first grade.

“I got into trouble. My grandfather taught me that . . . a quadrillion is a one with 15 zeros after it. I mentioned this to my first-grade teacher, and she said ‘There’s no such number.’ ”

Creating a scene that might sound familiar to some of Adragon’s teachers, De Mello described the way his grandfather immediately confronted the teacher. “He told her that if she wanted to stay in the teaching profession, she’d have to learn that there were numbers far larger than a quadrillion.”

De Mello contends that his formal grade school education lasted another two weeks. Pressed on what followed, he gives a cryptic grin, and falls silent.

What followed, by all indications, is that De Mello, in a decidedly unorthodox approach to education, got a masters in physics and astronomy from Metropolitan Collegiate Institute of London and a doctorate in theoretical astrophysics from Ohio Christian University. Then he took the high school equivalency and SAT test, and in 1974 earned a bachelor’s degree in English at UCLA.

“I was what they call an older student on campus,” he said of his time at UCLA. “I was in a scene on one end that Adragon was in on the other end.”

“Bear’s Guide to Non-Traditional College Degrees,” calls the schools from which he got his advanced diplomas “degree mills.” De Mello disputes this, saying they were schools for people who wanted to learn but didn’t fit into society’s niches.

Earlier this month, Florida Institute of Technology accepted Adragon into its graduate program, and offered Agustin De Mello an adjunct teaching position or a part time research job to help with the family finances, which now consist of what money remains of an insurance settlement and contributions from friends, De Mello said. On Friday, however, Andrew Revay, the school’s vice president of academic affairs, said that while Adragon remains enrolled contingent upon receipt of his UC transcripts, he looked into Agustin’s resume and there is now little chance that De Mello will be hired.

With a flourish worthy of Geraldo Rivera opening Al Capone’s vault, De Mello threw open his garage door, revealing “the catalyst behind this whole tragedy.”

The purpose of this hastily called press conference was to display water bottles and fuel additives in the trunk of De Mello’s Mustang fastback. Those “harmless substances,” De Mello said, explained a story that had found its way into the Santa Cruz Sentinel, in which De Mello, angered by what he saw as another roadblock to his son’s academic career, allegedly drove to the UC Santa Cruz campus in a car filled with gas cans, prepared to blow up himself and Adragon.

The source of that story says he told the Sentinel reporter about that “fantasy” off the record, to illustrate the sort of “fiction” that is being spread about De Mello. The reporter says the alleged incident “. . . was most decidedly told to me as something that actually happened.”

What everyone involved seems to agree, is that De Mello’s penchant for histrionics is a major source of his troubles.

In one recent example, De Mello told reporters that Adragon would soon set out on an unaccompanied odyssey to Australia, Europe, and the Soviet Union in search of a graduate school. Another time, De Mello, who said he and his son have been threatened frequently since becoming media figures, rushed what he thought was a bomb to the Santa Cruz Police Department. It turned out to be a package of chocolate chip cookies.

More serious, however, is the accusation that last year De Mello terrified the UC Santa Cruz math department with an ominous reference to Theodore Streleski, the Stanford graduate student who crushed the skull of a professor with a hammer in 1978. Gene Stone, chief of campus police at UC Santa Cruz, said a pervasive fear lingers in the math department now that De Mello is out on bail.

And the search warrant affidavit alleges that De Mello said, in a taped phone call to Gunn: “Remember what happened at ESL (the Sunnyvale computer company where seven employees were massacred in February, 1987) last year? Something like that could happen, only much worse if you screw up A.D.’s education.”

De Mello admitted he may have made certain remarks “for effect,” but said that he would not hurt anyone. His supporters scoff at the notion that he is dangerous, although De Mello does have a tendency “to excite paranoia in people,” said Ralph Abraham, who was Adragon’s professor in five computational math classes at UC Santa Cruz. “It’s just his style.”

Gunn in her phone interview emphasised that her custody suit was initiated earlier, and that the charges brought against De Mello are unrelated. She would not comment directly on the alleged threats, or on her assertion in the affidavit that De Mello often struck her.

Son’s Well Being

Speaking in a timid, pleasant voice she said only, “It’s not fair for anyone to make someone else frightened.” She added, though, that she is concerned about her son’s well being.

“I have a hard time seeing what A.D.’s benefit is out of all this,” she said. Agustin “says everything is for A.D. But I don’t see that all A.D.’s needs are being met,” she added.

De Mello and Gunn, though never married, lived together for at least nine years in Los Angeles, Santa Barbara and Santa Cruz, among other places. It’s not an issue Gunn will discuss, although she did elaborate on her own philosophy of life.

She said she isn’t sure whether either the father or his son are the geniuses Agustin makes them out to be, and doesn’t think the issue is terribly important anyway.

“I see people who say ‘I have a high IQ’ but the rest of their life is a shambles,” she said. “I don’t believe you should put yourself above everyone else because you have this genius thing. You should just fit into the rest of the world, do the best you can and try to be happy in the process of getting there.”

Like Agustin and Adragon, she takes great pleasure in creativity: Sewing Adragon’s hamster pajamas, for instance, or painting--the castle paintings on De Mello’s wall are her creations. But her aspirations are less grand than theirs.

“I don’t have high aspirations that I’ll be famous or anything. I just enjoy it. There are so many things to do in your life. . . .”

The child endangerment investigation now focuses on whether Adragon had a chance to enjoy life during his rocket ride through the educational system or whether De Mello inflicted ‘unjustifiable mental suffering,’ County Dist. Atty. Arthur Danner said Thursday. According to a press release from his office, “. . . investigators will follow all leads concerning the treatment and conditions that existed at the De Mello home so that ‘this boy’s life can be protected, and he can enjoy what all children are entitled to--a childhood that is filled with nurturing, love and care.”

Emotional Damage

Paul Lee refers to such concerns as “the Mozart issue . . . misplaced, sickening sentimentality about missed boyhood, as if this is an ideal world and you can cover every base.” As for any emotional damage: “I never saw a nuance of the father’s eccentricities in Adragon; he’s a perfectly normal 11-year-old, who happens to have exceptional abilities as well.”

Where Adragon stands on the matter of how to spend one’s childhood depends on who is interpreting his remarks. A page from his own health journal, scrawled in a childish hand, reads: “I took the test on Page 49 to determine whether I have type A or type B behavioral tendencies. The result indicates I have a moderate A behavioral pattern. . . . Being rushed and impatient and overly aggressive are patterns I must try to limit (to avoid a heart attack in later life).”

The theme reoccurred in a screenplay “Future Child” that Adragon wrote at Cabrillo College. In the play, about society’s abuse of a budding genius, the father has a heart attack and falls into a swimming pool. But “Future Child” has a happy ending: the young hero slips away to pursue his intellectual quest in New Zealand. His final line is: “It’s what my father wanted.”

Back at the house, De Mello pulled open the drapes for the first time that day, revealing what could be seen in the dark of the spectacular ocean view.

After turning on the television and VCR to record the evening coverage of his garage news conference, he began rummaging through two large file cabinets.

“At least 10,000” of the papers in the files are Adragon’s, he said. But “another 10,000” are his own, he added, and as if unloading Pandora’s box, he began pulling out some of his own eclectic body of work: an erotic story about a flamenco dancer that ends with a bomb explosion; a Mensa Research Journal article on “Structure of the Metagalactic System;” a poem for Garcia Lorca: “Execution / By the black squad / For the crime of poetry.”

Finding a love poem he’d written 25 years earlier, De Mello strolled across the room, and with Adragon’s albino hamster softly spinning its wheel in the background, played it on the piano.

“This doesn’t detract from my thoughts of Adragon,” he said. “This is creativity.” Clearly, De Mello’s life before A.D. was a mixture of artistry--Daily Variety called the young flamenco guitarist “an extremely talented musician”--and artifice.

In a self-published book of poetry called “Black Night,” for instance, the poems are about beauty, bullfights, dog sledding and death--and about De Mello: “The night is black / I have no woman / I have no friends / I am alone with my guitar.”

The foreword, by a Prof. E. Orlick, explains that De Mello’s first poem, written in elementary school, “showed some indication of the boy’s genius and earned him the highest literary mark in the school’s 50-year history.

A poem by beat poet Hugh Romney reads :”In this world of everyday / where men are small / and hide in giant suits / Agustin De Mello rises off the asphalt / like a breath of francis drake / before the crush / of nine-to-five / he is: a maestro of flamenco guitar / a fencing master /a champion weightlifter / an instructor of karate and judo /a racing driver/ a poet / these are his poems / ole!”

Romney, who transmogrified into the notorious Wavy Gravy in the 1960s, remembers De Mello well, even though he hasn’t seen him in over 20 years.

“He was always a little bit out there,” Gravy said. “I always thought he was quite a character, let me tell you. . . . A character in a sea of characters.”

Even then, as their folksie gang moved through the coffee shop scene with such unknowns as Bob Dylan and Peter, Paul and Mary, De Mello was always “very kicked back. But definitely a force,” Romney recalled. “There was always that latent power that the guy projected. I always thought he wanted to be Batman or something, with the fencing and judo and riding the big bike, etc.”

As for authorities’ concerns that De Mello may be dangerous, “In all the years I knew him, the only thing I saw him do violence to was a telephone,” Gravy said, refering to a time he watched “Auggie” rip a malfunctioning phone from a wall and calmly lay it on the bar where they were performing.

De Mello himself said he is incapable of hurting others, although he knows that there are some people who believe he is a bomb about to explode.

“No question. There are people who think I have an awful lot of explosive energy that is gathering more energy. But I think they’ve overlooked one thing. There is such a thing as implosion as well as explosion.

”. . . While they’re waiting for me to affect some kind of explosion out there,” he said, “it’s far more likely I simply will self-destruct with the tension, the great sadness. . . . Like a dragon, or dinosaur, I will simply become extinct.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.