Drifter Had a Fondness for Firearms

- Share via

SANDY, Ore. — The sparse portrait that emerged of Patrick Edward Purdy in the hours following his assault at Cleveland Elementary School in Stockton, Calif., was that of a young man who was troubled by his father’s early, violent death, had a poor relationship with his mother and was struggling to master a trade.

He had a fondness for firearms too, including what his aunt called “a big old ugly gun” that he bought last August while he was staying with her in tiny Sandy: a Chinese-made AK-47 rifle.

Since last fall, Purdy, who was born in Pierce, Wash., had rambled across the country in search of work. He had been laid off from a job in Oregon after attending welding school there. He told his aunt that the Boilermakers Union had told him there was a job in Dallas, but when he got there, the job had disappeared. He went to Memphis but hated the city and struck out for Cincinnati, where through the union he got another welding job.

It might not have been steady work, but it seemed an improvement from the life he had been living before, drifting between motels and boarding houses in Stockton and the nearby cities of Lodi and Modesto and using as a mailing address the modest, brown-stucco home in Lodi where his grandmother, Julie Chumbley, lives. Chumbley had not seen Purdy since last June and had not heard from him since Christmas, when he sent her a holiday card from Connecticut.

“The kid’s traveled the whole country since he was a teen-ager,” said a family friend, who was turning away reporters who came to Chumbley’s door after Stockton police identified Purdy as the man who shot 35 people and then himself.

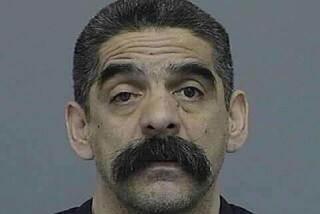

Stockton police said Tuesday night that they were still groping for a motive. Most of what the small, slender man with short, dirty-blond hair had done with his life seemed like so much small change.

Police arrested him for soliciting a prostitute in Los Angeles in 1980. Two years later, when he was again living here, he was arrested on a hashish-selling charge.

A year later, Beverly Hills police arrested him on a charge of possessing a dangerous weapon. The type of weapon was not listed in Purdy’s rap sheet, but he was sentenced only for a misdemeanor and drew probation.

In 1984, when he was living in Woodland, Calif., east of Sacramento, Purdy was arrested again on a robbery charge and convicted of being an accessory. Until Tuesday, that was the last crime for which he was arrested, according to California and Oregon authorities.

“It’s weird,” said his aunt, Julie Michael, in an interview on the front porch of her duplex in Sandy, 25 miles east of Portland. “Nobody really knows why. Do you think anybody ever will? It’s like a nightmare.”

Purdy’s father was killed when a car struck him on a dark street about five years ago, and the young man did not get along well with his mother, who has since remarried.

“He told me that he had camped out . . . while he was trying to go to school (in California) and make it on his own, because his mom had spent his Social Security money,” Michael said.

Joined Union

But Michael said Purdy, whom she described as intelligent, “was real happy with his life,” especially after joining the Boilermakers Union. Although police in Stockton described him as having had a drinking problem, Michael said that when he lived at her home last summer, he did not take drugs or drink excessively.

Still, in the manner of wanderers with criminal records, Purdy used aliases and fuzzed the details of his life.

He identified himself as Eddie Purdy West to the California Department of Motor Vehicles, and he said his birth date was 1962. He told the Oregon DMV he was two years younger.

Stockton police said he stood 5 feet, 7 inches tall, but Purdy listed his height as 5-feet, 11 inches when he registered with Oregon and California motor vehicle authorities.

Last June, when he decided to go to Oregon to stay with his aunt and uncle and look for work, Purdy answered a newspaper ad for a cheap 1977 station wagon, the one he would park just outside the elementary school gate Tuesday before setting it afire and walking 50 yards across the school grounds to begin firing his semiautomatic rifle.

“My impression was that he was just a typical drifter,” said Michael Fitzer, a Stockton engineer who sold Purdy the car. “He spent about an hour looking at the car. I would ask him a question, he would answer. He didn’t say a lot.

“I was asking $700, we agreed on $500. He said, ‘If you want the money, you’ll have to come with me.’ We went to one bank, he drew out $300, then we went to a check-cashing company, and he cashed a check for the other $200.”

Fitzer heard Purdy’s name on the radio driving home from work Tuesday. The name sounded familiar but he could not place it. When he walked in the door, his wife told him newspaper reporters had been telephoning. Then he remembered.

“That’s when I got scared,” he said.

Yet, looking back, Fitzer found it impossible to imagine that the young man in a white T-shirt and tight blue jeans would explode the way he did.

Nor could Pat Thomas, who shared a duplex with Purdy’s aunt and uncle in Sandy and met him last summer after Purdy left the San Joaquin Valley.

“He didn’t seem like any kind of violent person,” Thomas said in what has become the most unfortunate cliche of massacre postscripts. “He just seemed like a normal young man.”

Tamara Jones reported from Sandy, Ore., and Bob Baker from Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.