A STUBBORN ONE : Persistence, and Then Some, Takes Titans’ Staton to Brink of Pro Career

- Share via

At the age of 15 he signed his life away--acknowledging on the medical waiver that he was playing baseball against doctors’ advice and that if he died only his devotion to the game could be blamed.

When it came time for him to choose a college, he chose, only to find out the college didn’t want him so much anymore, which meant a nearly unbearable year and a half of practicing baseball but not playing it.

When he thought it was time to turn pro, having just completed one of the greatest summers any college hitter has ever had, the pros made an offer so measly that the attending scout refused to reveal it to him because he thought the offer “insulting.”

Dave Staton is a jilted lover. From the time he was 3, playing catch with his father, Bob, he has been true to baseball. By the time he was at Tustin High School, he knew it was what he wanted to do with his life.

“I couldn’t imagine doing anything else.”

But every step of the way his affections have gone unrequited. Baseball has always managed to leave him up in the air, dancing on the edge or shaking his head. There have been the broken promises, the half-hearted looks of scouts and recruiters, a bout with the disease lupus and the doubts about his talent.

“David has never had it easy,” said Orange Coast College baseball coach Mike Mayne, who coached Staton in 1986 and 1987. “You tell kids if they work hard and sacrifice, something good will come of it. But that didn’t happen for David. At least, not for a while. He always seemed to get the short end, he always got caught in the middle of something he didn’t deserve.”

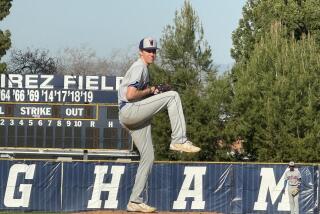

Until now. Staton, Cal State Fullerton’s designated hitter and leading candidate for hard-luck poster boy, is leading his team in home runs (14) and RBIs (53) and is hitting .381 Suddenly, a guy who couldn’t catch a break has broken onto the scene.

“I can see no reason why Dave won’t be hitting 30 homers a year in the major leagues someday,” said scout Joe L. Brown, who has been with the Pittsburgh Pirate organization for 40 years, including 25 years as general manager.

Staton, who is 6-feet-5 and 220 pounds, is first and foremost a power hitter, with the kind of power that reminds Brown of, “a young Dick Stuart.” Stuart hit 228 home runs in 10 major league seasons, including 42 in 1963 with the Boston Red Sox.

Staton was always big for his age. In second grade at Tustin’s Helen Estock Elementary School, he turned away near-daily challenges to his honor, which kept his pride intact but did less to endear him to the school’s staff.

“I had a lot of citizenship problems at that time,” Staton said.

He rarely played with kids his own age, his size and skills always forcing him into the older leagues. The first year he tried out for Little League, at the age of 8, he was placed in a league with 11- and 12-year-olds because, as his father, Bob, explains, “if he played with 8-year-olds he’d probably hurt them.”

The Senior Little League season before his first year of high school, Staton hit .800. He entered high school and played football, basketball and baseball. Sports had always been at the center of his existence--”David lived for sports,” Bob said. In his sophomore year, he played football and basketball, but noticed after the end of basketball season an unusual soreness in his legs.

Chalking it up to the wear and tear of the hardwood he set out for baseball, but the soreness got worse. Two weeks later he couldn’t walk without crutches.

“It was probably the scariest point in my life,” Staton said.

Doctors ran tests and came up with nothing. Finally they injected dye into his legs and discovered blood clots. They diagnosed that the clots were caused by a disease called lupus.

Lupus is a form of arthritis that inflames the body’s connective tissues and causes the immune system to produce antibodies that, instead of fighting off bacteria and virus, attack the body.

It took doctors awhile to diagnose the disease because, though 500,000 Americans are estimated to have lupus--more than 90% of them are women, according to the Lupus Chapter of Orange County.

Once diagnosed, doctors told Staton that football and basketball, and any other contact sport, were out. They were concerned that any jarring could move the clots from his legs to his lungs or brain and cause serious injury or perhaps death.

They also recommended that he not play baseball, worried of the same tragic result if he were hit by a pitch.

When he made the decision to play--”My love of the game just outweighed the dangers”--his parents supported him.

“You can’t live your life in a glass cage,” Bob said.

Dave signed a medical waiver releasing the school and doctors from responsibility if the worst happened.

“Now that I look back, that was a pretty big step for a 15-year-old kid to be making,” Staton said. “But, if I was faced with the decision again, I know I’d do the same thing. I wouldn’t blink.”

Staton took medication for lupus for three years and the disease has been diagnosed as being in remission.

In his senior year at Tustin, he hit .525 with eight home runs and was recruited to Orange Coast College. After two all-state seasons with the bat--he hit .420 and 370, and ended up with 17 home runs and 99 RBIs--he accepted a scholarship offer from Larry Cochell, then the baseball coach at Northwestern. He chose Northwestern because it was away from California--”I always thought that when you go to college, you should go away to college”--and because of its nationally recognized journalism department.

As a kid he taped Kings’ hockey games from the radio and practiced doing play-by-play. He played Chick Hearn to a friend’s Keith Erickson while sitting in the Tustin dugout during games. He wanted to go into either broadcast or print journalism after putting in 20 years of major league service and carving out a little place of his own in Cooperstown.

Kids do dream. But when Cochell left Northwestern to take the Cal State Fullerton job, which opened when Augie Garrido went to Illinois, it was nightmare time. With Cochell gone, the offer to Staton went from a three-year full-ride to two years at half tuition.

“Coming home, I just thought I had blown it,” Staton said. Mayne suggested that he enroll at Orange Coast for classes and work out with the OCC baseball team, which he did.

But, though he worked out with the team, he wasn’t part of a team.

“It was a tough year,” he said.

Mayne tried to get scouts and recruiters to take a look at Staton, but few seemed interested. He had been out of baseball for a year and a half. Though he had power, some questioned his ability to hit, even though he had never hit below .350 in any organized league since he was 8. And then there was the one-dimensional tag that stuck to him like a paste pot.

Staton’s best position is first base. But he got to Orange Coast at the same time as Rex Peters, an outstanding defensive first baseman. Peters played in the field, Staton was the DH.

“It had nothing to do with Dave’s skills,” Mayne said. “Rex is just a once-in-a-lifetime defensive player. Any other year, Dave would have played first.

“It was tough convincing people just to look at him. People looked at him as a one-dimensional player.”

Then Joe L. Brown took a look and liked what he saw. He convinced the Pirates to draft him and told his son, Ty, about him. Ty was then general manager of a team in Brewster, Mass., that was a member of the Cape Cod League, one of the oldest and most prestigious college summer leagues. Ty put Staton on his team for the 1988 season.

Through the many disappointments and scary moments, Staton had managed to keep his game face, but as he waited to go East, he was very nervous. A little more than two months before the league was to start, he broke his right hand. He could only start hitting 2 1/2 weeks before he was scheduled to go to Massachusetts. Another thing bothered him; the Cape Cod League used only wood bats, and he had never batted with a wood bat in a regulation game.

On top of that was the fact that he hadn’t played a real game in a year and a half. His worst fears seemed confirmed in a scrimmage before the first day of the season when he made two errors on the first two balls hit to him at third base. He struck out his two at-bats.

“I was scared to death before that first game,” he said.

He doubled in his first at-bat, and he went five for five that day with two home runs. That season he set a league record for home runs with 16. He also led the league in RBIs with 48 and his .358 batting average came within two points of winning him the triple crown, a feat never accomplished in the league.

“They were calling me Secretariat, but I really wasn’t aware of what I was doing,” said Staton, who was named the league’s most valuable player. “It was kind of like I was in a dream and I didn’t want anyone to wake me up.”

Then came the hearty wake-up slap in the face, though, when the Pirates, who had drafted him on Brown’s recommendation, offered him nothing.

“Joe told me he didn’t want to embarrass me with the figures,” Staton said.

The Pirates had waited to see what Staton would do in the Cape Cod League until they made their offer. Considering his season, the offer figured to be substantial. It wasn’t.

“I think they saw him in a couple of (Cape Cod League) all-star games and they weren’t as impressed as I had been,” Brown said.

True, Staton didn’t hit a home run in the all-star games, but he hit more than .400.

“I don’t know what else I could do,” Staton said. “When Joe told me, I wanted to cry.”

Brown told him on a Friday in late summer. It was too late to take any recruiting trips. The University of Missouri said they’d take him, but he would have to be on a plane that night. Fearing he was at the end of the road, Staton remembered that Cochell had promised him in April that he would hold a scholarship for him just in case things didn’t work out with the Pirates.

He flew home and enrolled at Fullerton on the first day of classes. There he found Cochell, one man who had kept his word to him, and Rex Peters at first base. Cochell likens Peters to Keith Hernandez . . . Staton became the designated hitter.

After a slow start he started hitting home runs. Big home runs. He hit one in a game against Florida State that Mike Martin, Florida State coach, said was the longest he’d seen in 14 years of coaching.

Last weekend, he hit five homers in two games against UC Santa Barbara. “I still can’t believe it,” Staton said.

Even though he’s considered a junior as far as his athletic eligibility--he is a senior academically--this will be Staton’s only season at Fullerton.

“David will not be back,” Cochell said. “He’ll be in the pros.”

It appears he’ll finally get his due come signing day. Baseball’s amateur draft is June 5-6.

Excited. Ahhh, yeah.

“My personality is the type that I always like being in control,” he said. “But it seemed like for such a long time my career was always in someone else’s hands . . . It’s great now, because I know that someday my life is going to revolve around the game.”

As if it hasn’t done a few hundred orbits already.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.