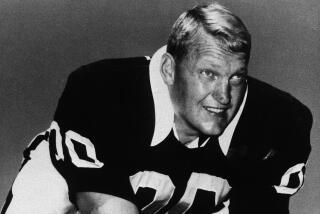

The Last of a Redskin Generation

- Share via

WASHINGTON — So football old is Dave Butz that he played when his sport actually was seasonal. The nephew of a former secretary of agriculture explained a habit he now will be forced to break:

“I would step up my workout routine as the wheat (near his Belleville, Ill., home) changed color. Wheat goes from green to light green to a mixed color to golden. When it got real yellow, I was ready to go to training camp.”

No longer. And when news that Butz will not miss the Midwestern wheat harvest this season, that the oldest NFL starter last year and the Redskins’ all-time leader in games played was calling it quits, a minicam blitz hit his home.

“One person was so excited,” wife Candy Butz said, “he blurted out: ‘You just blew China off the front page.’ ”

By announcing his retirement, although certainly in no retiring mood, the 38-year-old Butz severed the last and largest link between the winningest coaches in Redskins history.

George Allen brought Butz to Washington in 1975 for what seemed a sinfully high price: two first-round draft choices and a number two; Butz leaves Washington, after a firm shove from Joe Gibbs, with two Super Bowl rings and enough warm memories to keep the longest glory glow flickering.

Allen ordinarily is an unerring judge of football talent. Too late did he realize that the core of players he left after the 1977 season would help another coach realize his Super Bowl dream for the Redskins.

John Riggins came with Allen and, like Butz, left involuntarily. So did Joe Theismann, George Starke and a couple of Marks, Moseley and Murphy. Now Gibbs has made another of those painful decisions for which he gets paid so handsomely.

Nobody is saying so, but this tense ending probably followed a familiar theme: Butz believes loyalty should cause the Redskins to carry him another season; the Redskins believe that happened last year.

“I’m not going to say what I’ll be doing (in the future),” Butz said. “Somebody with more intelligence than I have might come up with a fantastic idea I might just jump all over.”

Here Butz paused.

“Meaning I’m open for suggestions.”

Retirement day was too hectic for meaningful reflection; besides, he had done a good deal of it fairly late in his career. While doing so, Butz answered critics, some of them Redskins coaches, who whispered he was too gentle to realize Hall of Fame potential.

“Every quarterback I hit knows I hit him,” Butz said. “If you mean do I have the ability to blindside a quarterback or hit him in the middle of the back as he’s throwing the ball, I have absolutely no problem with that whatsoever. To hit him with 300 pounds, plus about another 30 pounds of equipment.

“Because my problem in getting to him is immense. Once I’m there, I’m gonna hit him. But if I had to hit that quarterback -- I could take his legs out from under him, break his legs or whatever -- I wouldn’t do it. I’d still hit him high.

“I’ve broken collarbones, dislocated a few shoulders on some quarterbacks. On one quarterback, I heard the bone break, when Karl (Lorch) and I hit him. He was trying to get up and I said: ‘Stay down; you’re hurt.’ ”

Generally in the NFL, if a player lasts four years he can survive another five or so. It has to do with coming to terms with pain and experiencing teamwide ecstasy. That’s why Butz could play hurt and play Santa with equal enthusiasm.

“I love people who have the willingness to learn,” he said at an especially pivotal time. “People that have a quest, a thirst for learning, to be better, to improve themselves. I’d give up all-pro for a team, a defensive unit, that wanted to be the best it could be, that got after somebody, that played the defenses that were called. That’s what we’re tryin’ to do here.”

Seventeen days later, the Redskins won Super Bowl XVII.

Games with the Cowboys were semiannual Armageddons during nearly all of Butz’s 14 years with the Redskins. At a critical moment once, fourth down in Texas Stadium, Butz was within heartpounding earshot of Cowboy bickering.

Danny White tried to lure Butz and his buddies offsides with a long snap count. When that didn’t work, White called an audible. Almost instantly, Butz could hear the Cowboys center, from his hunkered-down position, turn his head toward White and mutter: “No ... no ... no.”

The Redskins soon threw that lousy judgment for a loss.

Butz has seen the evolution of football to a year-round business. Minicamps. Daily grunts through the weight room during the offseason. Intrusions such as these seem less offensive when salaries rise as they have.

Not surprisingly, all but a few of the Redskins -- players, officials and exceptional people with ordinary titles -- Butz recalls most fondly no longer are with the team. His generation of players has been absent for some time.

Butz talked about that shortly before the start of the 1988 season. Leaning against a wall at Redskin Park, he looked toward the far end of a practice field perhaps 150 yards away.

“The 10-yard line,” he said. “Just to the right of the goal post as we’re looking. That’s where I’ve stretched (during warm-ups) ever since I came here.

“Theismann and Moseley used to be close by. Brad Dusek was around. (Tom) Beasley and Curtis Jordan were around. (Ron) McDole and (Pat) Fischer. I used to eat lunch with Fischer. You feel like a piece of you left each time one of them did.”

Dean Hamel and some other thoughtful Redskins surely are thinking something similar.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.