Ligeti’s Eerie Hungarian Rhapsodies

- Share via

Blame Stanley Kubrick, but not too much. It was Kubrick who brought Gyorgy Ligeti his first 15 minutes of fame in 1968, when the director used recordings of the avant-garde Hungarian composer’s music (without his knowledge) in the film “2001: A Space Odyssey” to brilliant, if eerie and unsettling, effect.

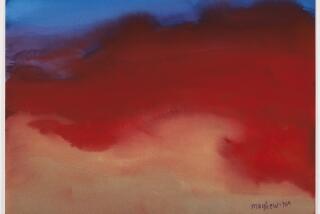

Suddenly Ligeti became the Space Age Bartok, and hippies began taking their own space odysseys accompanied by the psychedelic tone masses in the Requiem, “Atmospheres” and “Lux Aeterna,” which were included in the ubiquitous sound track release from the film.

It is of course not altogether surprising that Kubrick turned to Ligeti for the futuristic sounds of Jupiter rather than Stockhausen, Boulez, Xenakis or Berio, the other great postwar European avant-garde composers with whom Ligeti was closely associated.

Though sharing many of the same concerns in the late ‘50s and ‘60s as his cutting-edge contemporaries, Ligeti has always been the most visceral; no matter how far out it got, it was still earthy.

Now, two decades after “2001,” some of the sci-fi associations still linger around Ligeti, who will be one of the featured composers at the Ojai Festival, opening Friday. But that is changing.

Wergo, the German record label that specializes in new music, has made a cause of Ligeti lately, releasing eight compact discs of works of his from 1947 to 1985. They reveal a composer of remarkable breadth, one who has long reflected the musical culture of his time, whether the serialism of the ‘50s, the sound texture pieces of the ‘60s, minimalism of the ‘70s or eclecticism of our decade.

Born a Jew in Transylvania in 1923, Ligeti spent his adolescence in Nazi Hungary. He lost his father and brother to Auschwitz, only luckily surviving a labor camp himself. Studying in Budapest after the war, Ligeti was drawn inevitably to Bartok; his pieces written in Hungary in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s draw heavily on Bartok’s harmonies, his arithmetic meters and folk inspiration.

But it was Bartok with an edge. From the start Ligeti showed a passion for process, and his early works can sound like Bartok mechanized and skewered. Ligeti also demonstrated a rebellious streak and sardonic wit.

That sort of thing, of course, couldn’t last in Hungary, so when repression came in 1956, Ligeti went to Cologne, West Germany. He began working in Stockhausen’s electronic music studio, and he bought into the experimental movement, which allowed him to indulge his process-inspired thinking more fully.

This turned out to be just a passing phase. Once those sound masses began settling on single pitches or chords, harmony found its way back into his music. The rhythmic processes became more elegant, jazzier. Repetition crept in, and Ligeti developed a kind of advanced minimalism all his own.

Then Ligeti suffered his own apocalypse, a critical heart disease that prevented him from working for three years. But while continuing frail health and chronic high blood pressure have made travel difficult (and have prevented him from attending Ojai), he has returned to composition.

This late style happens to be both Ligeti’s most profound and most enticing, and there is no better way to enter into his sound world than through the Horn Trio, written in 1982 and found on two new recordings. It is rich in allusions to Brahms’ Horn Trio, with Ligeti’s characteristic machine-like metrical structures and his ear for vital sounds newly focused on melody and development.

And there is perhaps no better way to be introduced to Ligeti than through the haunting performance of the trio on a particularly rewarding Wergo CD (60100-50) that also contains Ligeti’s minimalist masterpiece “Monument- Selbstportrait-Bewegung” (with its second-movement tributes to Terry Riley, Steve Reich and Chopin) played with panache by Antonio Ballista and Bruno Canino (Ursula Oppens and Alan Feinberg play it at Ojai).

Also on the Wergo disc are three irresistible short cembalo pieces, including the dazzling “Hungarian Rock.”

For another, more determined, less mystical, approach to the trio, Bridge Records has released a CD (BCD 9012) that naturally pairs the Brahms and the Ligeti horn trios, featuring William Purvis as the solid horn player, but with different partners for each trio. A second, less dynamic view of “Monument-Selbstportrait-Bewegung” is also available on CD, this on Wergo (60131-50).

Another highlight of Wergo’s Ligeti series is the the CD containing the composer’s two string quartets played with remarkable precision by the Arditti String Quartet (which will offer the Second Quartet on its Saturday afternoon Ojai program).

Recommended as an introduction to Ligeti’s most coloristic orchestral music from the late ‘60s to the early ‘70s is the Wergo CD (60163-50) that includes the Double Concerto for flute and oboe (also featured at Ojai), the delicate, sumptuous, magically lit “Lontano,” the emotional Cello Concerto and the spectacularly frenetic “San Francisco Polyphony.”

But the best, single-disc survey of middle-period Ligeti is a new mid-priced reissue on Deutche Grammophon’s 20th Century Classics series (423 244-2) containing some of its Ligeti catalogue that includes sterling performances conducted by Pierre Boulez, Ojai’s music director again this year, of the Chamber Concerto, “Ramifications” and “Aventures,” along with the LaSalle Quartet’s warm and moving account of the Second String Quartet.

And what about “2001”? As heard in the digitally remastered sound track of a splendid new incarnation of the film on a Criterion Collection video disc, Ligeti’s music sounded as potent as ever. In fact, the famous climactic slit-scan psychedelia would probably feel awfully dated today if the music didn’t still sound so fresh.

Ligeti, it would seem, has a lot less to live down than we once feared he would have.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.