A Family Torn Asunder : In the case that became known as the Ninja murders, two brothers are accused of hiring assassins to gun down their parents after a business dispute.

- Share via

The attorney questioning Vera Woodman in a civil court proceeding wanted to know about her final conversation with her eldest son.

“Do you recall saying to Neil Woodman that if it was the last thing you did, you would see him and his family thrown out on the street and living in a $90 apartment?”

“That’s a terrible lie,” the dainty, soft-spoken witness protested.

“Isn’t it in fact true that is what you told Neil Woodman?” the attorney persisted.

Prophetic Testimony

“No. It’s the most awful lie,” she repeated, her voice choking. Then she added, in words no scenarist would dare to invent:

“How can you sit there and say that to me when I’d give him anything, including my life?”

Less than 18 months after this testimony, Vera Woodman was dead. She and her husband, Gerald, were killed on Sept. 25, 1985, in the garage of their Brentwood condominium building. The case became known as the Ninja murders because an eyewitness apparently confused a black-hooded sweat shirt worn by one of the assailants with the garb of a Japanese warrior.

Six months later, Neil Woodman and his younger brother, Stewart, were charged with hiring a team of professional assassins to kill their parents so the brothers could collect on a $506,000 insurance policy on their mother’s life. They have been held without bail since their arrest.

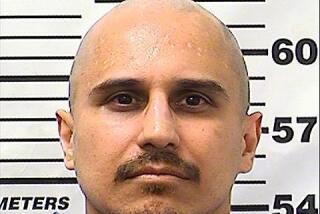

Finally, after much delay, the Woodman murder and conspiracy case is coming to trial. Jury selection is expected to conclude shortly in the trial of Stewart Woodman, 39, and one of the alleged co-conspirators, Anthony Majoy, 50, with opening statements scheduled for July 10. Neil Woodman, 45, and two co-defendants will be tried afterward.

Lawyers for both brothers say they had nothing to do with the killings.

“I am going to present facts unknown to the prosecution that . . . positively proves that he could not have been involved,” said Jay Jaffe, Stewart Woodman’s lawyer, who declined to elaborate.

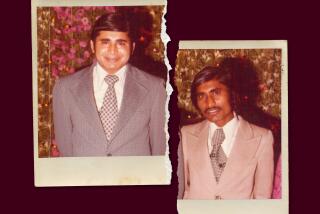

People who knew the Woodmans in the old days, when they seemed to lead such enviable lives, say it is hard to imagine how a family could be closer.

Settling in Los Angeles in 1948, Vera Woodman’s father bought four lots on the same street in West Los Angeles--one for each of his three married daughters, the fourth for himself. Growing up, Vera and Gerald Woodman’s sons were surrounded by cousins, and as young adults, they would remain within the family cocoon, working for either their father or their brother-in-law.

Many of those who came to know the Woodmans in recent years, however, say there was something else--besides their closeness--that drove this family.

The men were intensely competitive--some would say ruthless. Gerald taught his children that it was not enough to best an opponent, you had to crush him.

“If it’s your family, fight for them,” Gerald once wrote his sons, according to a court document. “If it’s a competitor, destroy them.”

So tight and ingrown was the Woodman clan--and so vindictive--that when a rift occurred, it tore them asunder with seismic force.

There was, for example, Gerald’s refusal to accept a settlement from his sons when the business relationship soured. Instead, he sued to dissolve the plastics firm they ran together; he lost and got kicked out.

Then there was the rival plastics business Gerald started in his 60s, determined to prove that he could not be cowed. The venture bankrupted him.

There was the five-year period during which Neil and Stewart would not allow Gerald and Vera to see their grandchildren, with the older brother going so far as to hire armed guards to keep his parents from attending his son’s bar mitzvah.

And if the prosecution is right, there was also murder.

Family Party

The bloody end came as Gerald and Vera were returning home from a family party in Bel-Air to mark the end of Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar.

Parking his Mercedes, Gerald opened the door. Suddenly, a man began shooting with a .38-caliber pistol, striking Gerald, 67, twice, and Vera, 63, three times. Ignoring Vera’s jewelry and the cash and credit cards in Gerald’s pocket, the killer fled.

Attorneys for Neil and Stewart Woodman acknowledge that there was conflict in the family, but deny that it led to a double murder.

The prosecution is expected to emphasize the relationship between the Woodman brothers and Steven and Robert Homick. Steven Homick, who was convicted in Las Vegas last May of an unrelated 1985 triple murder, is alleged to have fired the fatal bullets as part of a conspiracy with his brother, Robert, and Anthony Majoy. A sixth co-defendant, Michael Dominguez, pleaded guilty and is expected to testify against the alleged hit men.

Circumstantial Evidence

The prosecution hopes to tie the Woodman brothers to the murders with circumstantial evidence, including telephone records as well as a $28,000 wire transfer from Neil Woodman to Robert Homick made seven days after the insurance money was received, according to court documents.

At the heart of the Woodman case, however, is the relationship between sons and parents.

Although most family members, including the defendants, were unwilling to be interviewed, more than four dozen other people consented to discuss the Woodmans. Many asked not to be named.

Some, including Gerald’s sister and her family, believe that Neil and Stewart were incapable of killing their parents. “For anyone who really knew the family, it’s just too ‘Dallas’ to believe,” said Don Hymanson, the sister’s ex-husband.

What emerges is a portrait of parents who lavished material possessions on their five children, from elaborate aquariums and fancy bikes to shelves of cashmere sweaters; of a father who bullied his sons; of a mother who charmed everyone with her grace and femininity; of two sons who idolized and emulated their boisterous father.

The conflicts in the Woodman family did not erupt until after the death in 1974 of Jack Covel, Vera’s father, who “was the glue that held the family together,” according to a family friend. Covel had been a distributor of silent films in Manchester, England. Vera, the eldest of four girls, was only 13 when she met Gerald, the son of garment manufacturers.

When Covel moved into a custom tract home on Duxbury Circle, just west of Beverly Drive and a few miles north of what is now the Santa Monica Freeway, Los Angeles was undergoing its postwar boom. The Beverlywood community offered advantages to well-to-do young families. Boys could play baseball with their fathers in the street. Doors were left unlocked.

“On this block,” said Nina Roberts, who reared her family across the street from the Woodmans, “there was the kind of money that was not really conceived of before World War II.”

Despite the wealth that surrounded them, first Neil, and then Stewart, managed to stand out, neighbors recall. “Stewart was always bragging about how rich they were,” said Brad Yarbrow, who remembers taunting him in return.

Familiar Sight

Neil Woodman was one of the first kids to be given a new Corvette for his 16th birthday. Stewart’s first car was a Mustang, the trendy convertible that had just been introduced.

Covel and his wife were a familiar sight on the tree-lined street as they paid daily visits to their offspring. Each Sunday morning “J. C.,” or “Pops,” as he was known to his grandchildren, would make the “bagel rounds,” delivering breakfast and the paper.

Neighbors have vivid memories of the parties the Woodmans gave--the brunches and the brises, the bridal and baby showers, the birthday celebrations. The bar mitzvahs and weddings held at the Beverly Wilshire were “fantastic--like movie sets,” recalled Dr. J. Cutler Roberts, Nina’s ex-husband.

At family functions, some guests were amused to see the pool table in the Woodmans’ living room turned into a crap table.

Tender Toward Wife

The Woodmans seemed uncommonly devoted to each other. “I basked--and that is the word I used--I basked in the warmth that emanated from them,” Nina Roberts said.

A stocky, good-looking man, who at 5 feet, 9 inches towered over his tiny wife, Gerald was especially tender toward Vera, telling friends he could not sleep unless he was holding her hand.

He was often generous. Dr. Robert Karns, a relative and the family’s physician, recalls that Gerald gave Karns’ parents a blank check after they suffered a financial setback.

But Gerald, who shouted rather than spoke (probably because he was hard of hearing), was better known for his temper. “You never knew if there was another explosion about to take place,” one of Neil’s childhood friends said.

Another childhood friend remembers how Gerald put his foot through the television set after Willie Shoemaker stood up in the stirrups a moment too soon and lost the 1957 Kentucky Derby. Gerald was infuriatingly opinionated, with a sense of humor that could be hurtful.

Mocked Child

Louise Fox, a neighbor, remembers how Gerald, while walking his dogs, would mock her 5-year-old daughter by addressing the child as “Ugly.”

“I said, ‘Jerry, she runs and hides from you. She’s afraid of you,’ ” Fox recalled. “He said, ‘I wouldn’t say it if it were true.’ ”

His sons got the brunt of Gerald’s explosive anger.

Gerald “considered himself an expert in everything,” Yarbrow said. “When they bought the pool table . . . if he didn’t like how (Stewart) played, he would call him ‘moron’ or ‘stupid.’ ”

The insults continued, even after Neil and Stewart had married and fathered children of their own. “Vera would say to him, ‘Don’t yell at (Neil) in front of his wife. Don’t yell at him in front of their children,’ ” said Gloria Karns, Vera’s youngest sister.

Despite their father’s put-downs, both older sons, but Neil especially, revered Gerald and modeled themselves after him. “If ever a kid was more like his father, I can’t imagine,” Robert Karns said. But, said one friend, “Jerry was especially hard on Neil.”

Fondness for Gambling

Both sons picked up their father’s fondness for gambling. Robert Karns and others remember accompanying Gerald and Vera to Las Vegas, with the hotels picking up the room tab. At the time of his arrest, Stewart had large lines of credit at two Vegas hotels, said former Deputy Dist. Atty. John Krayniak, the prosecutor who handled the preliminary hearings.

The Woodmans met Steven Homick through a contact at the MGM Grand Hotel, according to Krayniak.

As he entered manhood, the short and slightly built Neil acquired some of Gerald’s rough edges, without much of the leavening charm. He was hot-tempered, argumentative and competitive. “I’ve seen him go crazy if the gardener turned the sprinklers on and got his car wet,” said Dennis Roberts, Nina’s son.

Stewart, regarded as boss at Manchester because of his talent for selling, could be tough and competitive--and worse.

Called Combative

Several lawsuits attest to Stewart’s combativeness. He sued his neighbors when they complained that his dogs were running free and sued his stockbroker for “breach of fiduciary duty” after a bad tip.

Among the customers the Woodmans sued was Jaco, a firm in Riverside. Stewart “said . . . he was going to make sure that Jaco was out of business for good if he was not paid,” the company’s general manager said in a deposition.

But people who knew Stewart only socially describe him as kind and generous. “The guy is just a big teddy bear,” said a close friend, Peter Wollons.

While his children were growing up, Gerald ran a succession of businesses, never settling on a single product. It was not making things, creating a business, that got his juices flowing, a customer said. It was, purely and simply, the competition.

“Whenever he went into a business he would say about his competitors, ‘I’m going to run them out of business,’ ” the customer said. “It was almost like he had to prove something.”

After World War II, he capitalized on the television boom and made antennas. Then it was aluminum sliding doors, then dinghies. Eventually, he and his father-in-law made extruded plastic, the kind used to cover light fixtures.

Narrow Profit Margin

Gerald’s genius, his sister-in-law Gloria said, lay in his ability to make things more cheaply than anyone else. Warren Kemp, a former national sales manager for Manchester, said Gerald beat the competition simply by cutting the price, even if that meant operating on a very narrow profit margin.

Given their volatile, demanding father, one might have expected Neil and Stewart to go their own ways, and for a few years, Neil worked for his sister’s husband selling municipal bonds, apparently with great success. But he left to join his father’s business, taking a pay cut. Stewart started working for his father at 17.

When Gerald Woodman struck out on his own and established Manchester Products in 1975, he gave his older sons half the business.

In 1978, in an event that was to prove critical for the family, Wayne Woodman, the youngest of the three sons, graduated from Duke University and arrived at Manchester. Vera Woodman, who owned the other half of the company, split her share with Wayne.

Unlike his older brothers, who were not college graduates, the better-educated Wayne had “an antiseptic, theoretical approach to management,” recalled their accountant, Harry Fukuwa. “He tried to influence his dad in these areas.”

Moreover, Neil and Stewart said later in court documents, Wayne started at the same $2,000-a-week salary they were getting and refused to pay his dues by becoming a salesman.

Gerald and his older sons also disagreed about the direction the company should take, according to former employees.

Stewart and Neil offered their father $2 million for his interest in the business, Fukuwa and others recalled. “I can remember telling Jerry, ‘This is the greatest testament to your success as a father,’ ” the accountant said. “ I told Jerry this was fair.”

Even though Gerald had suffered a heart attack in 1976 and was no longer working full time, he turned down his sons flat. Manchester stopped paying Gerald and Wayne their salaries.

In November, 1981, the father sued to dissolve the business, alleging that Stewart, who was in charge of marketing, was no longer willing to travel, Neil was shirking his responsibilities in the manufacturing end and both sons were harassing their younger brother.

Changed the Locks

One evening, while Wayne was celebrating his wife’s birthday, Neil and Stewart drove off with his car, according to court documents. They also sent a security guard to Gerald’s home to demand the return of his car, notified him that his medical insurance was being canceled and changed the locks. The brothers contended that the cars were company assets.

Portraying his father in court papers as “a compulsive gambler (who) has lost a fortune at the track” and squandered money on racehorses, Neil said Gerald interfered with the manufacturing process, causing bubbles to form in the plastic.

Gerald won a court order in 1982 giving him and Wayne $675,000. But instead of using the money for a comfortable retirement, Gerald--unable to accept defeat, according to associates--started a competing business that ultimately failed.

“He was mortgaging his whole fortune,” Fukuwa said. “To do this in his twilight years--it just didn’t make sense to me.”

Cause for Celebration

At Manchester, Gerald’s departure was cause for celebration. At first, the company, which by then had about 40 employees, was on a roll, and the atmosphere reflected that. “We had more fun, and more good times, than anybody in any company could ever conceive,” said Tom Brzoza, a former national sales manager.

When they were arrested in March, 1986, Neil and Stewart appeared the very model of successful businessmen. They lived in large homes--Stewart in the gated community of Hidden Hills, Neil in Encino--and played golf regularly at a country club in Tarzana. Their well-dressed wives lunched often at The Bistro in Beverly Hills.

But three days after the arrest, Manchester Products went into receivership. It owed Union Bank, its principal creditor, nearly $4 million, according to court documents. Six months later, the bank foreclosed and the company was sold.

Adding to Neil’s and Stewart’s financial pressure was a court order to pay their aunt, Gloria Karns, $107,000 by Sept. 29, 1985--four days after the murders. It was in connection with this business dispute that Vera testified she would have given up her life for Neil.

Former employees attribute Manchester’s slide to the move to a multimillion-dollar building, where a game room with a crap table was installed, and to the Woodmans’ high living, gambling and failure to recognize their limitations.

“We tried to expand too much over our head,” said Richard J. Wilson, a company vice president who was fired by Stewart. “We got into too many specialized products.”

Meanwhile, Neil’s and Stewart’s war with their parents continued. They would not allow Gerald and Vera to see their grandchildren. Birthday cards sent by Vera were returned unopened, Gloria Karns said.

Stewart, who “had a strong emotional attachment to his mother, almost as if the umbilical cord was not quite cut,” felt guilty about his behavior toward her, said his attorney, Jay Jaffe. “But he felt . . . if he opened the door a little bit, something would happen that would cause them (the children) grief.”

‘Feeling of Disappointment’

Stewart did not hate his father, Jaffe contends.

“It was more of a feeling of disappointment, betrayal or helplessness,” the attorney said. “He had his own family to support and protect, and he didn’t want to jeopardize that by foolish business practices.”

After the rift in the family was well under way, Vera’s sister, Muriel Jackson, tried unsuccessfully to have the insurance policy on Vera Woodman’s life canceled, according to court testimony. She was told that since Manchester Products was the beneficiary, there was nothing the family could do.

By the time they were killed, Gerald and Vera Woodman had lost the Bel-Air home they moved to in 1970 and had declared bankruptcy. The night of the double murder they were, true to custom, surrounded by relatives.

Fifty-two people, nearly all of them family members, had gathered at Jackson’s Bel-Air home to end the Day of Atonement. After breaking the daylong fast with smoked salmon and whitefish, the guests sat down to watch television.

The program they watched before Gerald and Vera started on the short drive home was “Dynasty.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.