THE JACKSON PHENOMENON The Man, the Power, the Message <i> by Elizabeth O. Colton (Doubleday: $19.95; 290 pp.) </i>

- Share via

Early in her account of Jesse Jackson’s 1988 campaign for President of the United States, Elizabeth Colton makes it clear that, although she worked as Jackson’s press secretary from January, 1988, until the election, she intends to include the unflattering as well as the laudatory. Colton briefly recounts the years that Jackson spent methodically building a power base with his own grass-roots organization, PUSH, originally People United to Save Humanity, though the save was soon replaced with the less grandiose serve. Colton notes the particular attention Jackson has paid to cultivating a following among the young. His first appearances at schools were in 1971, she points out, so one of the major Jackson constituencies was still too young to vote in 1988. They will, however, be of age in 1992. The many on-the-campaign-trail anecdotes make clear Jackson’s ear for a good line, witness his immediate adoption of the statement from a Klansman turned Jackson supporter: “I just don’t want to be on the wrong side of history again.”

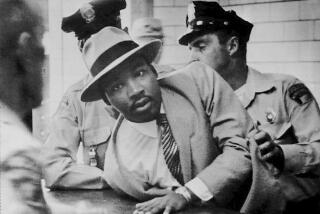

Colton also examines issues over Jackson’s history that came up during the campaign: his disingenuous account of his reason for leaving the University of Illinois; his heavy-handed negotiating on behalf of PUSH to establish “covenants” with corporations to hire blacks; his antisemitic remarks and continued association with controversial Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan. There was also the continuing rancor over his bid for black leadership upon Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s death. In her explanation, Colton says that Jackson regrets his behavior, but manages to leave the impression that he mainly regrets the problems the incident caused him later. Even without reviving past issues, Jackson’s behavior during the campaign gives rise to enough criticism on its own: his emphasis on loyalty over competence in his staff; his disinclination to relinquish control over any part of his operation; his reliance on a seat-of-the-pants approach; his struggle to control himself in relations with the press; his occasional abusiveness to members of his staff. There are no great revelations, however. Colton is not the first to suggest that Jackson’s drive for power is actually pursuit of legitimacy (he was born out of wedlock, as he said so often during the campaign), first as heir to King, then with his own political organization, and finally, as contender for the highest office in the land. Colton makes no secret of the fact that she found it extremely difficult to work closely with the candidate. What is unclear is whether Colton seeks to temper her admiration for Jackson with criticism in the interest of fairness, or whether she means to warn the public between the lines that Jackson’s volatile personality could be a liability in public office. Her ambivalence creates a curiously opaque account.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.