The Perils of Biography

- Share via

Since summer, as one of the judges on the biography panel for Britain’s Whitbread Literary Awards, I have gone through a succession of Lives. I enjoy biography; on occasion I even write it. But after reading my allotted third of the 72 contenders, I am dismally aware that true stories of real lives present problems that never disturb the progress of fiction.

The first is the Grandfather Barrier. No matter how extraordinary the subject of the biography, he or she is the offspring of two other mortals, themselves the product of four others. That means that pages, even chapters, can pass before Our Hero or Heroine appears at all. Feeding the reader with all this pedigree information is complicated by families which have the habit of bestowing the same Christian name again and again over the generations.

In his biography of James Joyce, the late Richard Ellmann had to deal with a great-grandfather and grandfather who were also named James Joyce. Ellmann got round this by dubbing the original the “Ur-James Joyce” and then revealed, thankfully no doubt, that only a slip of the pen by a drunken parish clerk had saved John Stanislaus Joyce, the father of the author of “Ulysses” from being named James as well.

Trendy biographers these days favor a prosy start. “Dr. Clarence Edmonds Hemingway, known to his friends as Ed, was not a man who much cared for cities.” Thus Kenneth Lynn introduces the father of Guess Who in his prize-winning 1987 biography. Then, like a camera panning a crowd, the author permits an early glimpse--but no more--of his subject, as Dr. Hemingway takes his children to the Chicago Natural History Museum where “by the time he was ten Ernest Hemingway’s favorite room was the Hall of African Mammals.” The reader can relax: The hero has been spotted, the “Green Hills of Africa” are in sight.

The stolid or scholarly biographer, in contrast, will head, with the zeal of a Mormon, straight for the family tree, up one side and then the other, forcing the attentive reader to reach for pencil and paper: “Alice Elizabeth Sheridan, known as Lizzie to her family, married John and Mary McCarthy’s second child, James Henry McCarthy in 1875.” (Carol Gelderman, in her recent biography of Mary McCarthy.)

Often the biographer unloads excessive genealogy simply because it is there. Certificates of births, marriages and deaths are fairly easy to come by (unless you’re writing anything about Ireland, in which case you will be told that the records were burned in the Dublin Customs House Fire in the Civil War). An oversupply of vital statistics, like weather reports of the birth day, are often put in as a substitute for what is not there. The between-the-sheets information, so de rigueur in biography these days, is hard to come by unless the subject wrote frank and durable letters or, better still, diaries.

Diarists make the biographer’s task incomparably easier (perhaps in anticipation). William Godwin actually kept a secret record of his sexual relations with Mary Wollstonecraft between 1796 and 1797 (as revealed for the first time in William St. Clair’s “The Godwins and the Shelleys,” a biography on the Whitbread short list). Fiona McCarthy’s biography of Eric Gill draws on his meticulous record of sexual favors bestowed upon, among many others, his daughters and the family dog.

Even before getting into the ancestors, the biographer has to deal with the book’s own pedigree. What are the sources? Which side of the inevitable row--family or academic--is the biographer on? And what is new? There is almost invariably at least one other well-known biography on the same person. The search for the undone subject is the biographer’s Holy Grail. What is the biographer’s attitude toward his predecessor: hostile or merely patronizing? All can be revealed in the acknowledgements, which--in this genre, uniquely--are irresistible.

Another primary decision facing the biographer is whether to intrude as narrator or to deliver the story unseen as from on high. There is no right way. There are some wrong ones--introducing the first-person for the first time on Page 345. Nor do I warm to the scholar hoping to turn an academic book into a best seller but retaining hopelessly academic touches, such as “Jennings has written” without an identification of Jennings. My pet hate is the scoutmasterly “Follow me, boys” tone, which puts the arm around the reader, and promises: “But Paris held a surprise for him, as we shall see in Chapter 12.”

The smugness of hindsight is the real danger of biography. We can see their fate approaching; they, poor clods, are blind to it. But biography should not be tragedy. Lives, even those which ended in disaster, were lived a day at a time. That some of the days were happy ones is conveyed by Anne Stevenson’s new biography of Sylvia Plath, but the sense of foreboding, as Plath’s suicide approaches, swamps the book.

Some deride the current passion for biography as prurient curiosity. A better answer has been given by the biographer Victoria Glendinning: “We have to make sense of life on earth. Human beings just do not have enough information about the conditions of their existence.”

Perhaps that explains why so many good biographies are about writers. Unlike painters, politicians, or scientists, writers use everyday life as their raw material and shape it with words, not only in the form of literature but also of letters, diaries, notes to the milkman--all biographer’s gold.

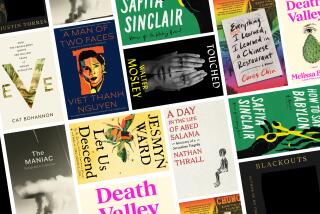

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.