The House That Bret Built : Ceremony: The Encino field where Cy Young Award winner Saberhagen played ball as a youth is being dedicated to him.

- Share via

On a cold and stormy Saturday morning early in February of 1973, a skinny 8-year-old named Bret Saberhagen strolled confidently onto a Little League diamond in Encino and, with nearly 200 other youngsters and dozens of adults peering on in utter amazement, proceeded to put on a baseball clinic.

The clinic was divided into four segments:

How to field ground balls like a blind man. In this drill, the boy had someone hit four grounders to him at shortstop. He missed all four, although witnesses recall that on one he nearly got close enough to have touched the ball with a 10-foot pole, which, unfortunately, he did not have with him. The other three he missed badly.

Playing first base like a hockey goalie. In this demonstration, the kid showed the crowd--which at this point was absolutely spellbound--that because actually catching a thrown baseball was far too difficult even to imagine, knocking it down or deflecting it was enough. He repeatedly showed his technique of allowing the fast-moving sphere to strike one or more parts of his body before it fell harmlessly to the ground.

How to throw a baseball as if it were an accident. In this display of skill, the kid moved back to shortstop and began throwing balls with uncanny accuracy at unconventional targets, connecting repeatedly with the dirt 20 feet in front of first base and another spot 15 feet up the chain-link fence behind first base. Some of the spectators, apparently bored with this drill, left quickly and returned to their vehicles, where they lunged inside, rolled up the windows and dived onto the floor.

Treating fly balls as if they were live hand grenades. In this segment, the youngster went to the outfield and began darting away from high-arcing baseballs. He easily eluded the first three, but on the fourth attempt he apparently misjudged the flight of the ball and it landed smack in the middle of his glove. Fortunately, it did not go off.

The onlookers were gasping.

“It was terrible,” said Little League baseball coach Mike Morris of Reseda, who witnessed the entire show. “He was the lousiest player of the day. It was just terrible.”

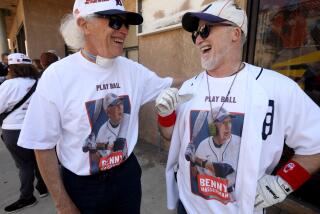

Today at noon, almost 17 years to the day after he brought his Larry, Curly and Moe Baseball Clinic to Encino, Saberhagen--now a 25-year-old man--will return to the same field.

And, in an elaborate ceremony, the field at Oxnard Street and Louise Avenue will be dedicated to him and will be named in his honor.

By whom, you might ask--the Red Cross?

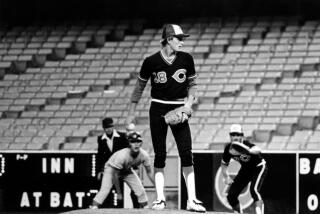

No. Saberhagen, the two-time Cy Young Award winner of the Kansas City Royals and inarguably one of the top pitchers in the major leagues, will be honored by the Mid-Valley Baseball Assn.

“That day was just a bad day,” Saberhagen explained Saturday.

Indeed.

Of the nearly 200 boys who attended that Little League tryout, Saberhagen was chosen last by the coaches who had gathered to scout the players. He lost out at a chance to be picked next-to-last when two coaches flipped a coin and the winner took the other kid.

The day was, however, a fluke. Saberhagen was already, at age 8, a solid baseball player. He was so good, in fact, that adults had been telling him just how good he was. And he believed them. So he stopped practicing. In one winter of non-use, his young skills had rusted.

He became the star on that Little League team in 1973 and continued to be the standout on every team he played on, including those at Cleveland High.

The trend has continued into adulthood. His 1989 Cy Young Award as the American League’s best pitcher will sit beside his 1985 Cy Young Award.

“By the time he was 10 and 11, he was way above everybody else on his team,” said Jack Jackson of Reseda, another coach who guided Saberhagen’s early career. “He was just an exceptional player, as a shortstop and as a pitcher. He was really something special to watch, even back then.”

That horrible February day in the drizzle might have been the best thing that could have happened to Saberhagen.

“For months leading up to that Little League season, I asked Bret if he wanted to practice,” said his mother, Linda, who was a main force in her son’s baseball life after a separation from her husband when Bret was 5.

“But he didn’t want any part of practicing. He told me, ‘Mom, I don’t have to practice. I’m good enough that I don’t have to. Everyone tells me that.’

“On the way home after that tryout, Bret cried. He said he hated baseball and that he would never play baseball again.”

Unfortunately for American League batters who spend much of their time trying to get even a small chunk of his sizzling fastball or snapping curve, Saberhagen was persuaded by his mother to give it another chance.

And the embarrassing lesson that Saberhagen learned stays with him today.

“I use that story a lot when I talk to kids,” he said. “I learned that even if you have some talent for something, you can’t just walk in and expect to be good at it. I mean, I couldn’t throw a single ball to first base that day. I knew my capabilities. I knew I could play as well as anyone else. But I didn’t work at it.

“From that day on, I realized that I couldn’t coast. If you want something, you have to work for it.”

And work he did. Within days, a tire hung from a tree in the family’s back yard and a crude pitcher’s mound was marked off 60 feet, 6 inches away. And within a couple of years, that 13-inch tire might as well have been a hula hoop as the kid began buzzing strikes through the center.

Saberhagen’s father found out the expensive way that his son had been practicing.

“We used to have bets,” Bob Saberhagen said. “We’d each throw 10 baseballs. Each one through the tire was worth a quarter. We’d throw all day long. One day, when he was 10 years old--and remember, I was a healthy 35-year-old man--he won $60 from me. Sixty dollars!

“That was the day we stopped playing that game.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.