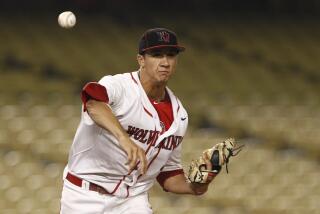

Westlake Catcher Hitting His Stride

- Share via

At one time, they couldn’t give Mike Lieberthal away. He was a tiny 12-year-old who wanted to play with the bigger boys, but they didn’t care to play with him.

Howie Shwartzer, a coach in the Woodland Hills Senior League, could only smile when a league official offered him this scrawny kid who wanted to play with the 13-to-15-year-olds.

“He called and said he had a little guy from Westlake named Mike Lieberthal,” Shwartzer recalls.

The book on Lieberthal was that he was 4-foot-9 and probably couldn’t hit his weight.

Shwartzer, who had previously coached Lieberthal and knew otherwise, tried not to sound sarcastic. “Well, we’ll do the best we can with him.”

Today, Lieberthal is 6-foot, 165 pounds, and has become the player everybody wants. The senior at Westlake High is hitting .558 with nine home runs and 24 runs batted in, and is one of the most sought-after prospects in the nation. Area scouts project him to be selected in the first three rounds of major league baseball’s June 4 amateur draft.

“If there’s a better catcher in the nation, I want to see him,” one scout said.

Pitchers avoid throwing him strikes.

Scouts scribble notes.

Students organize fan clubs.

The kid who pleaded for an opportunity to play varsity baseball at Westlake High, who spent endless hours collecting as many blisters as line drives in a batting cage, has become a minor legend on the Westlake campus.

“You begin to wonder what it is that this kid can’t do,” said George Genovese, a professional scout for 26 years.

The hiss of the pitch broke the silent anticipation of the crowd last Wednesday at Westlake High.

Lieberthal shifted his weight, turned his hips, snapped his wrists. And as the ball kept sailing, he headed toward first base in a sprint-turned-trot. As he rounded third, his teammates patted him on the back and pounded his helmet.

Lieberthal, who already had taken a curtain call after his third home run of the game, had just hit his fourth.

He blasted a three-run shot off Simi Valley ace Kenny Hood in the first inning. He drove a fastball over the left-field fence for a solo shot in the second. He turned a curveball into a grand slam in the fifth. And, in the sixth, he deposited a low fastball on the junior-varsity field some 400 feet away.

Lieberthal’s fourth home run tied a Southern Section record set by two other players. He drove in 10 runs and had five hits.

“It was one of the most awesome performances I’ve ever seen,” Simi Valley Coach Mike Scyphers said. “Mike is the best catcher I’ve ever seen at the high school level. He just has that aura about him, and really stands out.”

Yet Lieberthal barely had a leg to stand on when he entered Westlake High four years ago.

He had played with minor league baseball players as a 14-year-old competing in a winter league. But a 5-4, 130-pound ninth-grader out of Colina Intermediate School had trouble getting into Coach Dennis Judd’s sixth-period baseball class.

“I went into his office every day for about a week, begging him to let me in the class,” Lieberthal said.

Eventually, Judd was persuaded.

“He’d do anything,” Judd said. “Not only to get into the class, but he’d do anything on the baseball field. He’d play anywhere you asked.”

Lieberthal worked his way into the starting lineup at second base. Judd’s decision to start a freshman, rather than a senior, drew criticism from parents. “I took some heat, but he was very talented,” Judd said.

Lieberthal wasn’t an instant hit, and a designated-hitter occasionally filled his spot in the batting order. But his father directed him toward their back-yard batting cage. Dennis Lieberthal invested about $1,500 in the cage and a pitching machine when Mike was 9. With his mother, Anita, feeding the machine (once taking a line drive in the face), Mike worked in the cage as long as two hours a day.

“A lot of parents used to tell me that he was playing too much baseball, that I was pushing him too hard,” Dennis Lieberthal said. “But I wasn’t pushing him, he was pushing himself. It’s hard to explain that to people.”

Mike’s dedication became an obsession.

“There were many times when he was 10 years old and his friends were out riding bikes when he was in the batting cage,” Dennis Lieberthal said. “He could have gone out with them, but he just stayed home and hit.”

Mike said he has no regrets.

“I know baseball is my future, and whatever I do now will dictate what happens in the future,” he said.

Lieberthal has played more than 400 games the past four years. Two summers ago, Dennis Lieberthal hired Doni Green, a former Simi Valley track coach and an assistant at Cal Lutheran, to improve his son’s running form and speed.

Mike Lieberthal worked with Green for about two hours a day, five days a week. Then he would leave for the ballpark.

“He was a very hard worker,” Green said. “And a pretty busy cowboy.”

Perhaps most critical to Lieberthal’s development as a player was his experience playing with minor league players on winter league teams sponsored by the San Francisco Giants, Houston Astros and Toronto Blue Jays.

Lieberthal has caught Trevor Wilson, who pitches for San Francisco’s triple-A affiliate in Phoenix and briefly pitched for the Giants last season. Lieberthal singled off Eric King, a former Royal High player who pitches for the Chicago White Sox. And he doubled in his only appearance against Roger Salkeld, the former Saugus pitcher who was selected third overall by Seattle in last June’s major league draft.

Genovese said Lieberthal’s skills made up for his lack of size.

“George kept yelling, ‘Hey, kid! Who ya play for? Who ya play for?’ ” Dennis Lieberthal said.

Mike replied, “Colina!”

Genovese scratched his head. “Where?”

“Colina Junior High!” Mike said with a grin.

Since then, Lieberthal has played for Genovese’s winter league teams and developed a close relationship with the scout who signed George Foster and Garry Maddox.

“The best way to describe Michael is to say that he comes to the ballpark to beat you,” Genovese said. “He plays the game as if it was a religion, and you’ll probably see him in the big leagues in about three or four years.”

It’s difficult to find a scout who isn’t fond of Lieberthal.

“The first time I saw him was during a tryout camp last year,” said one scout who requested anonymity. “He threw a ball down to second and I said, ‘Who is that ?’ ”

Lieberthal throws the ball from home to second base in 1.8 seconds; 2.2 is considered average at the major league level. He runs to first base in 4.5 seconds, which is above average for a catcher.

Some don’t need numbers to be impressed.

“I saw him catching during an infield practice, and that was all I needed to see,” said Ray Poitevint, vice president of the Milwaukee Brewers. Poitevint is a former scout who has signed 60 players who have played in the major league.

“Just his footwork and arm were enough to impress me,” he said.

Lieberthal drove away from his four-homer game in a BMW with personalized license plates that read MIDLINF.

A two-year starter at shortstop during his sophomore and junior seasons, Lieberthal moved to catcher this season. He played the position in the rookie leagues, and decided the move would provide him with a better opportunity to play major league baseball.

“It’s a quicker ticket to the big leagues because everybody’s in need of a good catcher,” he said.

His catching skills have been honed by the Dodgers’ Rick Dempsey. And his lanky-but-strong build has led to comparisons with the San Diego Padres’ Benito Santiago.

Poitevint prefers a comparison with Enos Cabell, a player he signed out of L.A. Harbor College who was overlooked in five drafts but eventually enjoyed a 15-year major league career.

“Enos would do whatever had to be done, and that’s how I feel about Lieberthal,” Poitevint said. “The first one to the field and the last one to leave.”

Lieberthal picks runners off base from his knees, and his soft hands behind the plate impress scouts, who follow every move.

“I used to get real nervous,” Lieberthal said. “I’d try to throw the ball too hard, or try to make a perfect throw every time, and it would just screw me up.”

Lieberthal, who received his first letter from a university when he was 14, will sign a letter-of-intent today with Arizona State.

But Lieberthal may never step into the batter’s box at Packard Stadium. If he is drafted in the first two rounds, he will sign a professional contract.

“It isn’t just the money,” said Dennis Lieberthal, a part-time scout with the Giants and a successful businessman. “It’s the investment they have in you for the round. A first-round pick is pretty much a sure thing, and they’re given every opportunity to prove themselves.”

Mike said if he signs a contract, he will work on his education during the off-season. Poitevint recommends that approach.

“This boy, with the type of skills he has, isn’t going to refine them playing college baseball,” Poitevint said. “He can always go to school, but he can’t always become a professional baseball player.”

His father agrees.

“If he plays pro baseball, he’s not giving up an education, he’s giving up a chance to play college baseball,” Dennis said. “Now, it would be different if Michael had a dream to be a lawyer.”

But he doesn’t. Lieberthal’s idea of defense involves blocking a 55-foot curveball.

“I want to be a professional baseball player,” he said.

“But if I’m not drafted in the first two rounds, I’ll be completely happy with going to Arizona State. I’ll go there, work hard, and hope I’m drafted again after my junior year.”

The chant echoed from Westlake’s bleachers as he approached the batter’s box.

“Dong, dong, dong!” they yelled.

Two pitches later, he sent a hanging curveball into oblivion.

After he crossed the plate, the chant took a different tone.

“God, god, god!”

The billing, as humorous as it is, now follows Lieberthal.

He has led Westlake (15-0) to the No. 1 spot in the 5-A Division and a No. 5 national ranking by USA Today.

Shwartzer knew his tiny second baseman, who also did some catching, would be a catch someday. He even teased his starting catcher, Mike Urman, who was selected in the second round by the Atlanta Braves in 1987.

“I used to joke around with Mike and tell him that this little kid was going to be a better catcher than he ever was,” Shwartzer said. “Little did I know that my words would come true.”

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.