Wally Moon Finds Satisfaction in Minors

- Share via

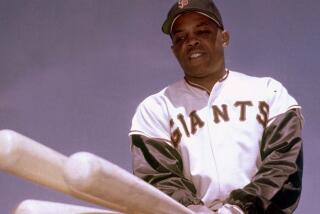

FREDERICK, Md. — At first glance he might look out of place to the casual observer. The graying temples give him a distinguished look that not even a baseball uniform can hide.

He stands on the top step of the dugout watching each pitch. Every move is charted in his mental computer. He is surrounded by kids younger than his own children.

Two of those charged to his care are Pete Rose II and Keith Kessinger, whose fathers played against him in the major leagues almost three decades ago. To him, a generation gap is nothing more than a difference in age. Tell him he looks, and sounds, like he could be a teacher and he will smile. The man has a master’s degree in education from Texas A&M.;

Make no mistake about it, Wally Moon is a teacher.

That’s what brings him to the foothills of the Catoctin Mountains to manage a Single A baseball team. That’s what enables him to endure bus rides that test the mental and physical endurance of men half his age.

He is not a career minor-leaguer, like many in his profession. He has spent more time on college campuses than some professors.

He has also spent most of his life on baseball diamonds. And, at the age of 60, he has no immediate plans to change his lifestyle.

This is Moon’s first year as manager of the Frederick Keys, the Baltimore Orioles’ Carolina League farm team. It is his first year in the organization, only the fifth year he has managed a minor-league team.

What propels him to continue? What drives him to put on a uniform instead of packing a fishing pole?

“I’m challenged by the teaching process,” said Moon. “I’m interested in young people. I like to be around them, work with them, see them do things.”

It is more than an hour after a recent Keys’ game -- a 2-1 victory over Lynchburg -- and Moon is still fully dressed in his uniform, except for the hat. There is paperwork to be done, but that can wait.

“A ballgame like this one today thrills the hell out of me,” Moon said. He had brought in Todd Stephan to protect a one-run lead in the ninth despite the fact that Jeff Bumgarner had struck out 12 in the first eight innings.

Stephan retired three hitters to preserve the win and give his confidence another charge. “He was unsure of his role before,” said Moon. “Now we’ve identified a role for him and he’s responded. He believes in his stuff and his progress. It’s something you love to see.”

Stephan has earned saves in all six of his opportunities in the second half of the season. “Tim Holland is another good project,” Moon said of his Carolina League All-Star outfielder. “I think some people in the organization were ready to give up on him, but I saw things I liked, and wanted him.”

Patience is obviously a key to Moon’s approach, dating back to his playing days. A left-handed hitter who came up with the Cardinals, he made an art of hitting to the opposite field after being traded to the Dodgers, who briefly played “screeno” with the left-field fence in the Los Angeles Coliseum.

Moon disappeared from the professional scene when his playing career ended in 1965, but he hardly reached this stage of his career by accident.

“The children were growing up, drugs were starting to come on the scene, and I decided I didn’t want to raise my family in southern California,” Moon said. He and his wife, Bettye, have five children. “I sought out a small school (John Brown University) in Arkansas and spent 15 years there as baseball coach.

“My wife and I are both small-town people at heart, and we chose to stay in one place to raise the family. Part of my deal was that the children got an education for free -- and believe me, that was a major factor in the decision.”

In 1977 something possessed Moon to get into the ownership end of professional baseball. “I bought the San Antonio team, with the idea that my son (Wally Joe) could run it after getting out of graduate school,” he recalled. “But my general manager got promoted to a job in Rochester during the winter meetings and the next thing I knew the season was ready to start and I didn’t have any program ads or tickets sold.” To protect his interest, Moon ultimately got out of college coaching and took over operations of the San Antonio team. “Before I knew it, I was $250,000 in debt,” he said. “It took me six years to get out. I lost a little bit, but I almost lost my butt.”

Moon spent a half-season coaching at Louisville in 1986, after Jim Fregosi left to manage the White Sox, but his interest is whetted more by life in the low minors.

How long will he continue?

“As long as I feel as good as I feel now, and somebody will give me a job,” he said. “I feel really good physically and mentally. The bus trips don’t bother me. I can still throw batting practice if I have to -- I don’t, but I could if it was necessary.

“I sat out last year. I tried that retirement bit, and it wasn’t worth a damn.”

So he rides the buses and communicates with starry-eyed youngsters who hope to play in the big leagues.

He watches players like Rick Gutierrez, his shortstop who was named to the Carolina League All-Star team, or pitcher Arthur Rhodes, who was recently promoted to Double A, and understands what they need to develop. “Everybody knows they’re prospects,” said Moon. “My job is to smooth them out.

“Gutierrez gets down on himself at the plate, and he carries it out to the field. So you get him going with the bat, and then you talk to him.

“Rhodes went up because he had to have his ability challenged,” said Moon. “He didn’t go up necessarily because of his record, and he’s still a little unsure of himself. He needs to get confidence in all of his pitches instead of just throwing the ball by hitters. It’s better for him to be up there where he won’t be able to rely just on the fastball.”

But for every Gutierrez and Rhodes, there are many more like Stephan and Holland. They are the ones who keep Moon in the game. They are the ones who keep him young and make the bus rides bearable.

The minor leagues can be an education in itself, as anyone who has been there will attest. For Wally Moon, teacher, it is the perfect classroom.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.