NEWS ANALYSIS : Sharp Differences Emerge Between Wilson, Feinstein : Politics: The candidates have taken divergent positions on taxes, school finance and the environment.

- Share via

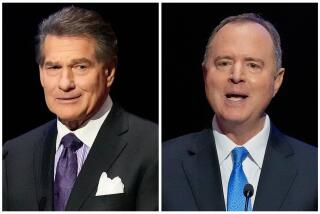

As their contest for governor approaches a critical test in October, Democrat Dianne Feinstein and Republican Sen. Pete Wilson have established sharply divergent positions on key issues like higher taxes, school finance and the environment--defying the perception that there are no substantial differences between the two political moderates.

California political analysts and commentators have repeatedly characterized the race as dull, contending that the candidates are ignoring the real issues and that Feinstein and Wilson seem more like philosophical soul mates.

But during September, when their campaign often was overshadowed by the Middle East crisis, the candidates added considerable meat to their skeletal policy positions, either in speeches or in response to questions from reporters. The result has Wilson sounding more conservative and cautious, particularly on money issues. Feinstein is more willing to talk about the need for expanded state programs and new state revenues to pay for them.

The continuing state fiscal crisis--with the potential for additional taxes simply to support existing programs--has emerged as a defining issue that could dominate the candidates’ televised debates on Oct. 7 and Oct. 18.

In light of the temporary balancing gimmicks used to stitch together the long-delayed state spending plan, the new governor is likely to face a multibillion-dollar deficit in drafting his or her first state budget.

If California still needs more revenue after making whatever budget cuts she could, Feinstein said, she would raise the income tax rate for the most wealthy Californians, couples making $200,000 or more annually. The top rate was reduced in 1987 from 11% to 9.3%. Feinstein also has endorsed Proposition 133, which would raise the sales tax by half a cent to pay for anti-drug and crime programs.

Wilson, by contrast, has said it would be foolish to rule out the need for new taxes, and has refused to do so, but he has said he would oppose any increase in personal income tax rates. This week, he strongly endorsed Proposition 136, which would require a two-thirds vote of the Legislature or the electorate to increase any state or local tax.

But while he declined to endorse Proposition 133, the sales tax increase, he said he might vote for it. On Thursday, Wilson said that if Proposition 133 loses, he would be willing to consider an effort in the Legislature to raise the sales tax half a cent for anti-drug and crime programs.

The candidates also differ on budget reform, school finance and Proposition 98, the 1988 initiative measure that guarantees public schools at least 41% of the state’s general fund revenues each year. That amounts to about $17 billion this year out of a total budget of $55.7 million.

Feinstein, with the support of state Supt. of Public Instruction Bill Honig and the California Teachers Assn., has declared Proposition 98’s guarantee “inviolate” and vowed to oppose any effort to change it. She favors budget reform that would reduce the level of spending required for some programs by state law or the state Constitution, but would not cut back on most major health and welfare programs, which account for nearly a third of the general fund budget.

Wilson also wants budget reform, but insists that all state spending items, including Proposition 98, be on the table for negotiated changes. The only exception is that Wilson would oppose any cuts in the state’s supplemental Social Security payments for the aged, blind and disabled--a program that costs $2.3 billion a year.

Both candidates are considered strong environmentalists, but again there is a key difference. Feinstein is endorsing Proposition 128, the far-reaching Environmental Protection Act of 1990 dubbed Big Green by its supporters. Wilson opposes the proposition.

Both Feinstein and Wilson also promise to be activist governors who will attack problems such as California’s unbridled growth.

But Feinstein promises the more aggressive effort, describing her approach as a “new awakening” fueled by “the politics of optimism and rebirth.” Appearing at an Orange County Democratic meeting in Anaheim earlier this month, she talked of running a “creative administration” like that of Edmund G. (Pat) Brown in the 1960s “that built the best university system and built the California Water Project.”

“I want to be the governor that says, ‘Wake up, California. Let’s move this state into a problem-solving mode, let’s develop that water policy, let’s solve the problems of the environment, let’s manage our growth. . . . ‘ “

Wilson vows to be the real candidate of change but his efforts could be hampered by his anti-tax stance and conflict with the Legislature’s Democratic leadership.

It has been a struggle for the candidates to get their messages across in a period when Saddam Hussein and his Aug. 2 invasion of Kuwait continue to dominate the news. Feinstein has been dogged by questions about the business dealings of her financier-spouse, Richard Blum, who joined with Feinstein in lending her campaign $3 million for her primary election.

Labor Day marked a major turning point, leaving behind a desultory summer of exchanges of costly television commercials in which the candidates tried to taint each other with allegations related to the savings and loan crisis.

The policy differences between them were accentuated by Feinstein during September as she ventured into the risky world of taxation, pledging support for billions of dollars for existing state programs and campaigning for stronger environmental regulation.

The July-August television campaign seemed to result in a standoff. Going into September, the major public opinion polls indicated that the ad campaign had little effect. The two candidates were considered to be running about even, just as they were after the June 5 primary. October and its two scheduled debates provide Feinstein and Wilson the opportunity to capture the undecided swing voter.

“There are a large number of people who sort of see Dianne in a positive context, but they have been comfortable with Wilson the way people are comfortable with an old pair of shoes,” said Bill Carrick, Feinstein’s campaign director. “Those people, in my view, have been postponing their decision until they get some point of comparison that is beyond the 30-second commercial.”

Some political experts have said that Feinstein has to make some sort of breakthrough to capture voter imagination and defeat Wilson--something akin to the dramatic television commercial that propelled the Feinstein image into the public consciousness in her primary campaign. The ad showed Feinstein firmly taking control of San Francisco as acting mayor after the shooting death of Mayor George Moscone. The commercial has not been rerun since the June 5 primary.

Both campaigns say they want to continue discussing issues during October rather than getting into another television commercial shoot-out. Wilson’s theme, campaign director Otto Bos said, will be: “It’s performance that counts, not promises.”

With 23 years of experience in the Legislature, as mayor of San Diego and U.S. senator, Wilson has a broader record of which to boast. Feinstein held public office for nearly 20 years, but entirely at the city and county level in San Francisco.

Carrick said Feinstein intends to continue to emphasize issues and the intangible values of leadership, believing that voters are getting turned off by an “electric Ping-Pong” exchange of personal and negative television ads.

“We’ve been specific on issues,” he said. But he also noted that Wilson “has beaten up on us on taxes.” The senator constantly reminds voters that he actually cut some taxes as mayor of San Diego while Feinstein raised levies in San Francisco.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.