Character Assassination : John Updike Kills Off ‘Rabbit’ After Decades of Scrutinizing Society’s Flaws. Now What ?

- Share via

NEW YORK — Rabbit is dead, but John Updike swears it was a mercy killing. After all, if a famous literary character wants to load up on junk food, laugh off a heart attack and then die heavily in debt, who can stop him?

“I don’t like killing off characters, because I’m not very good at saying goodby,” Updike says with a chuckle. “But Rabbit had to go, as much as I loved him. His time was up. He was tired of everything, getting weary of sex and living in general.”

A shrewd coroner might also list writer fatigue as the cause of death. After 30 years of chronicling the life and times of Harry (Rabbit) Angstrom, a high school basketball star-turned-American Everyman, Updike admits he simply ran out of gas. It was time to quit.

His decision will come as a shock to millions of readers, who have followed Harry’s ups and downs through “Rabbit, Run” in 1960, “Rabbit Redux” in 1971 and “Rabbit Is Rich” in 1981. With the completion of “Rabbit at Rest,” (Knopf, $21.95) Updike says he looks forward to taking a rest, then breaking new literary ground.

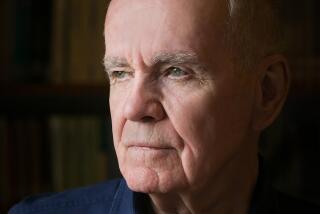

The 58-year-old author, whom John Cheever called “the most brilliant and versatile writer of his generation,” has produced an astonishing 39 books, including short stories, criticism, novels, plays, children’s books, memoirs and poems. He has won numerous awards, including the Pulitzer Prize, and is acknowledged to be one of America’s most multitalented authors.

But he is perhaps best known for the Rabbit novels. Published at 10-year intervals, they have been hailed by some critics as Updike’s darkest, most ambitious work. Through the eyes of his WASP antihero and other characters, Updike has captured the changing American scene, beginning with the 1950s and rolling through the greed-ridden 1980s.

Some readers thought the books would go on forever, but Updike says that was never in the cards: “These novels really couldn’t continue beyond this last one, because there was the danger of them turning into a comic strip that never ends. I was trying to write an American life, and so I guess you can say that I hustled Harry into a premature senility.”

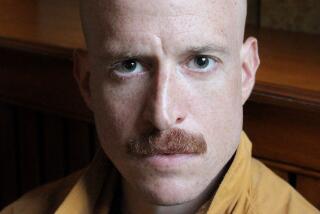

A lanky, soft-spoken man who flashes an elfin smile when he speaks, Updike doesn’t look the part of a literary eminence. He is warm and engagingly unpretentious in a hotel interview, wearing simple gray slacks and a plain white shirt. Fresh from the “Today Show,” with makeup still on, the New England author seems more interested in talking about the Boston Red Sox and their latest swan dive than his most recent novel.

“I guess the Sox are a lot like Harry Angstrom,” he says with a little shrug. “You know they’re going to stumble eventually. But you’re also amazed that they hold on as long as they do.”

In “Rabbit at Rest,” the 225-pound Angstrom finally expires after clogging his arteries with gobs of junk food. Brushing aside a doctor’s warning, he eats bowls full of salty corn chips and nearly has a fatal heart attack. Back on his feet, he keeps eating fried foods and winds up comatose in an intensive care unit, clinging to the last moments of his life.

Along the way, Rabbit bickers with his wife, broods about death, makes a hash of his relationship with a drug-addicted son and has an appalling sexual encounter with his daughter-in-law. The book charts Angstrom’s final journeys, hopscotching between Harry’s sterile life in a Florida retirement colony and the drab Pennsylvania town where he was born.

As in previous books, Rabbit turns and runs when life’s problems get too pressing, hence his nickname. He is a difficult character to like, an ordinary man writ large against the backdrop of a changing society.

Asked to describe the final installment of his series, Updike calls it “a depressed book about a depressed man, written by a depressed man.”

But “Rabbit at Rest” is more than psychology. Running 512 pages, it is a scathing, almost nihilistic take on the United States today. In Updike’s view, the nation is addicted to junk food, television and foreign debt--a land overcome with spiritual fatigue as the Cold War ends.

He also paints a dark picture of the American middle class in decline. Harry and other white members of the Silent Majority may have once felt confident about the future, he says, but they are now in danger of being muscled off the political stage.

At one point, Rabbit wonders what’s the point of even being an American, now that Soviets are no longer the enemy and the Japanese are buying up everything in sight. His life in a Florida condominium community is filled with boring rounds of golf and shopping trips to a sun-bleached mall. When relatives visit, he is hard-pressed to fill up the time. As his chest pains increase, he lapses into a prolonged funk.

“There’s a kind of emptiness to Harry’s life, and that got to me,” Updike says. “And it’s true that I’ve loaded onto him the responsibility of reflecting the times. There’s a heaviness and a sluggishness about the book, a sense of weariness throughout.”

It’s also an unusually autobiographical book, even for Updike, who has in the past woven themes from his own life into his novels. While writing “Rabbit at Rest,” for example, he experienced a midlife depression of his own. His mother was dying in Pennsylvania and he was wracked with guilt, fearing that he was not spending enough time with her.

Back in Florida, Harry reflects that darkened mood when he begins watching hours of television and gobbling macadamia nuts. There’s a telling connection, the author says, because “television is a kind of mental junk food in our time. I don’t know if TV builds up in the arteries like corn crisps, but (we’re) overfed and under-nourished by it. There’s an awful lot of knowledge around and not much wisdom.”

Rabbit’s dietary death wish also echoes Updike’s life. Like his character, he was born in the Pennsylvania Dutch country and grew up on a diet of doughnuts, shoofly pie, pretzels and other starchy foods. Although he is trim for his age, the author has fought a lifelong battle to keep his weight down and eat healthy meals.

The parallels deepened even more when Updike began writing about Angstrom’s heart attacks. Shaking his head, the author recalls that he experienced chest pains as well. A doctor pronounced him healthy after an EKG test, but Updike insists that he did not feel fully recovered until he finally delivered his hefty manuscript to his editors in New York.

“I wouldn’t say they were severe pains, but the more I read about cardiac trouble the more symptoms I seemed to have,” he notes. “I think it’s a common thing. . . . If you sit in a room and think about any joint or part of your body, you can inflict some pain on it, can’t you?”

In the book’s grand summation, Updike delivers a sermon on debt and accountability in modern America through the story of Nelson, Harry’s do-nothing son. Although the Angstrom family has run a profitable Toyota dealership for years, Nelson has secretly embezzled thousands of dollars to feed an expensive drug habit, and he bleeds the company dry.

When he is confronted with his crime, Nelson takes refuge in a drug detoxification center. After months of treatment, he begins spouting homilies about “personal rebirth.” The son says nothing about the money that was stolen or whether he should be punished.

“Isn’t that the way we are?” Updike says. “You have a druggy kid and instead of spanking him you send him to detox. I think that’s a good mirror, because nobody pays in this society. The idea of paying for your sins seems to be an obsolete notion. It jibes with the whole S&L; crisis, and with (former President Ronald) Reagan, who is a wonderful example of a man whom things slid off of.”

Ultimately, however, there is retribution: A Japanese Toyota executive visits Rabbit in Pennsylvania and demands that the family’s staggering debt be paid in full.

“It’s the voice of reckoning,” Updike says. “And isn’t that how we see the Japanese, as sort of the price we’re paying for our sins? We’re lazy and fat, we watch television and drink beer while the Japanese are drinking rice water.

“God speaks in the end,” he adds, “but in a funny accent.”

It is a bitter lesson for Rabbit, who has been buffeted by cultural turbulence before. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, he was swept along by the drug craze, radical politics and wife-swapping. But his values remained firmly right of center: Harry supported the Vietnam War, voted enthusiastically for Reagan and dressed up as Uncle Sam in a Fourth of July parade.

“Rabbit is among the many of humble origins who now make up the Republican majority, at least in presidential elections,” Updike says. “But there’s also a populist resentment in him. . . . He does dislike the rich somehow, even though he’s become somewhat rich.”

Again, there are strong parallels with Updike, who like Harry Angstrom rose from humble economic origins to a position of middle-class comfort in the past 40 years.

Born in 1932, Updike was raised in the small town of Shillington, Pa. His lower middle-class parents worked hard to make a living and sent him to public schools. Although the fledgling author won scholarships to Harvard and Oxford, he never quite lost touch with his economic roots--even amid the trappings of literary success.

At 21, he began writing essays and literary criticism for New Yorker magazine, a tradition which continues. Updike flourished in Manhattan’s literary world, but felt intuitively that he would not be able to write novels in the city. He moved to Ipswich, Mass., in 1957 and has lived there since. Divorced and remarried, he has raised four children.

Although Updike has taken generally liberal positions over the years, he was uncomfortable with dissent against the Vietnam War and once criticized protesters’ “aesthetic distaste” for President Richard M. Nixon. He also rejected the “snobbish dismissal” of President Lyndon Johnson by the Eastern Establishment, saying it demeaned the country.

“I can’t claim to have real blue-collar roots or anything, but I have in a way tried to remain loyal to the middle class,” Updike says. “You know, the un-colleged, sort of semi-buried down there . . . not in a ghetto, but not living in summer homes, either. Harry and I together have been forced upward in the social scale.”

The Rabbit novels, he explains, have given a voice to people “who are under the affluent level, who struggle. They are in history and they feel all of the cultural currents, from the Pill to civil rights. But they all feel it in a kind of muffled way . . . because it’s a struggle for them to get ahead and survive.”

Some critics suggest that Updike has gone overboard in his use of Angstrom to convey a literary world view. In a recent New York Review of Books essay, Garry Wills complains that the author has superimposed his own perceptions on a character who does not read much, is not sophisticated and could not possibly make such complex, intellectual observations.

When Harry visits a lover who is dying, for example, Updike writes, “He pities the room, its darkness, as if even weak window light would penetrate her skin and accelerate the destruction of her cells, its hushed funereal fussiness.”

Updike acknowledges the criticism, but says his license as a writer allows him to deal with a higher plane of reality. Most people aren’t writers, he notes, “so just by giving any person a dramatic stream of consciousness you’re falsifying. Just like Shakespeare had people talk in blank verse when they don’t really. People are a little more sensitive in a novel than they are in real life. . . . They’re more alert to each other and to other things.”

Now that Angstrom’s story is over, Updike says he will next publish a second collection of his essays and literary criticism. He also plans to begin a novel next year, saying only that it will be based in the 1970s, “in pre-AIDS America . . . something of a paradise lost.”

The distinction is crucial to the author, whose works have traditionally overflowed with sex and seduction. In the Rabbit novels and such best-selling books as “Couples,” which dealt with marital infidelity in a small town, he has explored the subject in spicy detail.

On occasion, Updike has paid a price for this fascination. On the request of lawyers, he cut 500 offending words from “Rabbit, Run” in 1960. He has also been criticized by feminists for his treatment of women in “The Witches of Eastwick” and “S.”

“I think there’s a good firm biological basis for sexual interest,” Updike says with a grin. “We’re programmed for it, and Freud gave his blessing to it. He said it’s all right, of course we’re sex obsessed. Mental health is basically sexual health.”

Today, the cultural climate has changed and it is unlikely that Updike would be asked to censor one his novels. A writer can get away with anything, he says, but “as long as there’s a barrier, your duty is to push against it and write all the dirty words, to see, to test.”

Updike leans back on a sofa and squints at the sunlight pouring through the hotel window. Asked if there is even a remote chance that Rabbit Angstrom will return from the dead, he smiles and looks like a man from whom a burden has been finally lifted.

“I love Harry and I hate to give him up. But it’s by no means certain that, 10 years from now, I’ll be able to write,” he says. “Maybe I’ll get a stroke, or be kidnaped and become a hostage in the Middle East. I just didn’t want to leave the series dangling. So it’s done.”

It’s a closure that Updike knows well and has admired in others. About 30 years ago, he wrote a New Yorker essay about the last game played by Ted Williams, the legendary Boston Red Sox slugger. Updike was moved by the finality of Williams’ last home-run trot.

“On the car radio, as I drove home, I heard that Williams had decided not to accompany the team to New York,” he wrote. “He knew how to do even that, the hardest thing. Quit.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.