FICTION

- Share via

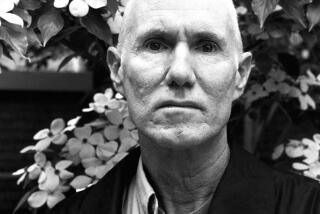

LAST LOVERS by William Wharton (Farrar, Straus & Giroux: $18.95; 368 pp.) . William Wharton is one of those novelists who keep trying to match the success of their first books. “Birdy,” published when he was 52, was a magical evocation of boyhood and friendship, a treasury of bird lore, a flight into the realms where vision and madness merge, and a hard-hitting tale of World War II combat, all written in plain, sturdy American. If his eighth book, “Last Lovers,” doesn’t soar to the same heights, it isn’t from lack of ambition.

John Updike has written that the novel as a literary form is primarily a love story, and that its decline is due to the erosion of social and religious barriers that used to make love perilous and interesting. As an example of the desperate expedients now necessary, he pointed to Vladimir Nabokov’s “Lolita,” which charts the fever of a 40-year-old man for a 12-year-old girl. Given the importance that men place on physical appeal, Wharton sets himself an equally difficult task in “Last Lovers”: to make us believe in a love affair--spiritual and sexual--between a man in his late 40s and a woman over 70.

The man, Jack, is an American who has left his family and his high-paying job at an IBM-like firm to live like a bum in Paris and pursue his original dream of being an artist. The woman, Mirabelle, was blinded by the shock of a childhood tragedy. In solitude, she has become a superb cook, sculptor and musician (and, since this is a Wharton novel, an expert on pigeons). After she and Jack literally bump into each other on the sidewalk, her wisdom and innocence help him resolve his conflicts and find his true force as a painter.

Wharton, too, is a painter, and he has lived in Paris for many years. “Last Lovers,” accordingly, is full of concrete and persuasive detail. But Jack and Mirabelle are conceptions that haven’t quite crystallized into characters. Indeed, Mirabelle (whose dialogue and thoughts are printed in copperplate script) is so extraordinary a conception that Wharton seems, unwittingly, to be saying that an older woman has to be a virgin and a genius to be plausibly loved. He seems afraid to break the spell with normal plot complications; the romance proceeds so smoothly that it’s unreal and a little dull. Still, Wharton “fails” here with a project that few novelists would even attempt.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.