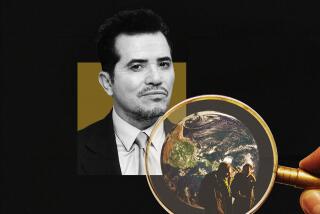

SEMINARY DAYS : The Reformation : The Rev. Rafael Luevano, rector-president of St. John’s, says change is necessary for the survival of his students--and the church.

- Share via

In the dormitory hall of St. John’s Seminary College hangs a 1977 senior class picture: two dozen earnest young men in black suits, including a tallish fellow at one end with dark features and a blinding smile.

In those same halls, that tallish fellow now strides from appointment to appointment as if he runs the place.

He does. The Rev. Rafael Luevano, 36, officially took over the job of rector-president at St. John’s one year ago.

“We have students here who are older than I am,” he confessed one recent morning.

But his agenda for multicultural seminary reform has raised more eyebrows than has his age.

“Change is hard for everyone, including me,” Luevano said. “But for the health and survival of the seminary and the church--and most of all, the survival of our seminarians--we are called to do it.”

In an unusually blunt address to church officials in Boston last month, Luevano went even further.

Noting the rising numbers of Latino and Asian seminarians on his campus, the young rector-president asserted that “our educational and formational programs, effective for another generation, lag in the face of cultural diversity. Our faculties are suddenly unprepared, personally and professionally, for a change that is already upon us.”

Luevano, the son of Mexican immigrants, started at St. John’s in 1973, and went on to graduate studies in Europe. His academic specialty was 16th-Century mysticism, not a typical college administrator’s training. But before he was named to the top job at St. John’s, he had served as a parish priest in Costa Mesa and returned to the campus as spiritual director and professor of theology and Spanish.

He often favors casual dress (though he vanishes to change when a photograph is proposed) and maintains an office with six caged finches and Guatemalan needlework on the wall. Hoping to remake the institution’s image, he carefully reviews catalog illustrations and recruitment brochures himself.

“He gets about four hours a day of sleep,” said his secretary, Karen Gundelfinger.

Much of the remaining 20 hours, it seems, go into shaking up campus life.

‘He’s done some very unorthodox things,” said Juan Torres, one of the 14 students in the college’s undergraduate class of 1991. “I don’t like some of the things that he’s done.”

Sophomore Benedicto Camacho Morales, on the other hand, was relieved to transfer to St. John’s from a more conservative seminary. There, “seminarians were expected to fulfill a certain ideal.” At the new St. John’s, he said, “people were in jeans and tennis shoes. Some had long hair. People were just themselves.”

When Luevano was a seminarian, morning prayers were at 5:30 and you didn’t miss. The men would shuffle into the chapel, dip their fingers in holy water and settle into assigned pews. A priest kept roll. Now the prayers are at 7, and no one keeps roll. The list of further administrative reforms is long and varied.

But the most obvious change at St. John’s in recent years may be the color of the seminarians’ faces. After years as an Anglo-dominated institution, the seminary now houses a student body that is two-thirds Latino and Asian.

“Having an Anglo, upper-middle-class model of priesthood just doesn’t work for a Vietnamese, or Mexican, or Salvadoran,” said Luevano. “We’re encouraging the guys to be themselves in their national and cultural attitudes. . . . It’s a more contemporary, updated notion of ministry.”

That contemporary view is evident in the latest St. John’s recruitment brochure, overseen by Luevano. Instead of the the usual stained-glass windows and affable middle-aged priests, the brochure shows a seminarian’s chaotic desk: An Apple computer, a collection of Flannery O’Connor short stories, a half-eaten doughnut, a Reebok sneaker, a pair of jeans tossed over a chair, and, hanging at eye level, a crucifix.

“To make a difference in the year 2000,” says the brochure, “be different now.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.