Mime Artistry Finds Its Voice With Pomona College Teacher

- Share via

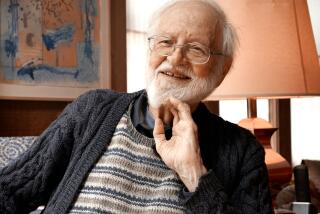

Thomas Leabhart winces at the stereotype of mime: silent whiteface a la Marcel Marceau.

To Leabhart, a writer, teacher and artist at Pomona College, mime is a timeless art that can use words as well as movement to express a wide range of ideas.

The intense, soft-spoken professor is a mime who relies on vocals, videos and most of all his body to spin his tales. And no, his performances are not conducted in whiteface.

Leabhart, 46, who chairs the theater department for the Claremont Colleges, founded and edits Mime Journal. The eclectic magazine included in recent editions stories on no theater, a classical style of Japanese drama, as well as Latino performance artist Guillermo Gomez-Pena, who just received a $230,000 MacArthur Foundation “genius grant.”

What makes Leabhart unique, critics say, is his synthesis of artistry and academics. Experts say that he has carved out an important niche in theater as well as in intellectual scholarship.

“Tom’s work is in the tradition of the avant-garde theater while . . . also maintaining a great . . . awareness of art history,” said William Fisher, theater professor at the California Institute of the Arts and co-founder of the Los Angeles performance group Zeta Collective.

Leabhart concedes that modern mime will never give the Martha Graham Dance Company or the Bolshoi Ballet competitive pause. Nonetheless, he has devoted his career to educating the public about this little-known and sometimes maligned art.

To Leabhart, modern mime involves breaking down the body into discrete parts that can be recombined much the way individual musical notes are strung together to form a melody. He explains his theories in a 1989 book “Modern and Post-Modern Mime,” which is used in classrooms and drama schools throughout the United States.

Leabhart is a disciple of the late French artist Etienne Decroux, whose expressive, abstract movements based on the rhythms of living things was christened corporeal mime to distinguish it from the anecdotal, whitefaced mime popular in the 19th Century.

Leabhart has won grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the California Arts Council and traveled through Eastern Europe researching Slavic mime traditions.

His performances have graced some of the Los Angeles area’s seminal--and now defunct--performance spaces: Wallenboyd downtown and The House in Santa Monica.

Los Angeles Times critic Robert Koehler has called Leabhart’s works “mime on the cutting edge of invention, far from Marceau’s shadow . . . disarmingly witty . . . suffused with irony and sadness.”

Marguerite Mathews, who studied under Leabhart and founded the Pontine Movement Theater in Portsmouth, N.H., said her mentor is “absolutely unique in the field.”

“He’s the galvanizing point around which festivals and conferences happen; he’s got a wonderful vision about what the field needs to advance and leave a legacy,” Mathews said.

The Claremont scholar also has a loose definition of the word mime. He includes performance artists who often use outrageous means to critique society, politics, censorship and sexuality.

Profiles in the Mime Journal have included those of such people as performance artist Mark Pauline, who constructs grotesque machines of destruction, and John Fleck, who catapulted into controversy when his NEA grant was yanked last year because of the allegedly obscene content of his work.

“These people are mimes in the best sense of the word, a modern-day commedia dell’arte,” Leabhart said, referring to the Italian Renaissance troupe that performed penetrating social satire.

The Italian players “would go into a town in the morning, figure out which priest was tippling Communion wine and which mayor was stealing from the coffers, and in the evening they’d put on a show, much to the delight of the crowd and consternation of the officials,” Leabhart said. “Then they’d move on. They’d have to.”

Leabhart traces the history of mime to Herondas, a Greek who lived in Alexandria, Egypt, around 270 BC and left 13 mime plays written on papyrus scrolls. At that time, mime performances were always accompanied by some kind of text, he said.

Some cultures split theater in two: actors who moved silently across the stage and those who narrated the action. Leabhart said this tradition continues in some South Indian and Asian performances.

He traces true silent pantomime to 1697, the year that Louis XIV expelled the Italian players from Paris because they mocked his mistress. From then on, the troupe was allowed to play only on the condition that they not speak.

Other European actors soon copied what they saw in France, and the trend spread quickly, to reach its contemporary apex in Marceau, who popularized a form of mime primarily using his face and hands.

With the advent of modern and postmodern corporeal mime, “it’s not silent anymore. Mime has found its voice,” Leabhart said.

The performer found his artistic voice as a child in Pennsylvania, where he staged plays in unused rooms at his father’s funeral home.

He majored in art during college but his pieces grew progressively more kinetic and three-dimensional until a professor told him: “This isn’t art any more, it’s theater.”

In 1968, after seeing a film of mime master Decroux, Leabhart headed to Paris on a Fulbright fellowship with hopes of looking up this artist who so compelled him with the beauty and purity of his movement. He stayed four years, winding up as Decroux’s personal assistant.

At Pomona College, Leabhart teaches mime, theater literature, mask work and group play creation. He believes that all actors must learn the basics of movement to fully assume their roles.

He deplores mime-bashing in popular culture. The movie “Scenes From a Mall” features a scene in which Woody Allen’s character wreaks revenge on a whitefaced mime who follows him in a shopping mall.

For his part, Leabhart said he no longer gets angry with those who misunderstand his type of mime.

“I still get calls saying, ‘Will you perform at my son’s bar mitzvah?” Leabhart said. “These days I just refer them to someone else.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.