Ripken Had Real Future as a Pitcher

- Share via

BALTIMORE — It may be hard to believe, and even tougher to accept, but Saturday is the 10th anniversary of the major league debut of Cal Ripken Jr.

On Aug. 10, 1981, two days after his recall from Rochester, Ripken made an unlikely first appearance. “Pinch-runner for Ken Singleton, scored the winning run on a double by John Lowenstein--I remember it like it was yesterday,” Ripken said.

What he also remembers, and few people outside baseball realize, is that it almost didn’t turn out this way.

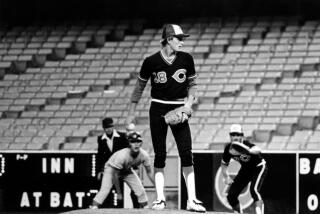

Today Ripken is the American League’s perennial All-Star shortstop and one of the premier players in the game. But it was as a pitcher that he first attracted attention while playing at Aberdeen (Md.) High School.

And, with one exception, every team that considered Ripken as a potential pick in the 1978 amateur draft listed him as a pitcher, not a position player with power potential. In an era of high-tech individual scouting, including a central bureau from which all teams can draw information, it is rare that any facet of a player’s ability escapes notice.

Every once in a while, however, one slips through the cracks. That apparently was the case with Ripken, although having his father on the coaching staff and a major-league park available for thorough, and private, workouts certainly gave the Orioles an edge.

The Orioles were the only team that rated Ripken as a position player. For the most part, that was because of the foresight and persistence of a scout, who almost 10 years earlier practically escorted Al Bumbry to the big leagues.

Dick Bowie lived long enough to see Cal Ripken Jr. make it to the big leagues, but unfortunately not long enough to realize how accurate his judgment had been. His advantage over other scouts was knowing Ripken’s desire to play every day -- and scouting him on days that he didn’t pitch.

“I never saw him play the infield,” admitted Joe Branzell, the longtime area scout for the Washington Senators and Texas Rangers. “Looking back now, you realize that he pitched every big game.

“The fact that he was also playing shortstop when he wasn’t pitching probably took something away from his arm in both positions. That’s something that might not have been taken into consideration at the time, but I definitely think the Orioles had an edge. They weren’t going to take the chance of missing out on the son of Cal Ripken Sr.

“Dick (Bowie) and I were good friends, but we never talked about Cal,” said Branzell, who managed the Washington Boys Club, the counterpart to Baltimore’s nationally known Johnny’s team, for many years. “I think Dick might have hid him a little bit.”

Bowie didn’t have the opportunity to hide Ripken -- he was out there for the baseball world to see -- but what he did do was hide the fact that there was more to this kid than pitching.

“Everybody likes him as a pitcher,” Bowie said shortly after the Orioles made Ripken a second-round draft choice. “But I think he can play the infield in the big leagues, and I’m not sure he can’t play shortstop.”

The only other person who voiced that opinion was the one who had the most to do with Ripken settling into the shortstop position. It might have been the best observation former Manager Earl Weaver ever made.

At the age of 17, Ripken was considered a good prospect by most, but not all, scouts. Branzell’s report noted “little short on fastball velocity,” but also pointed out similarities between Ripken and Jim Palmer.

One scout who admits he didn’t like Ripken is Walter Youse, a longtime scout for the Orioles, Angels and Brewers. “I saw him once and got him only at 81 (mph),” Youse said. “He got high school hitters out with curveballs and he didn’t hit or run.”

The irony is that Youse’s first assignment for the Orioles was to scout a catcher in Aberdeen. “Jim McLaughlin sent me up there to see if I thought he could play in the Arizona State League,” Youse recalled. “I came back and said yes, they brought him into the office and signed him.”

The catcher’s name: Cal Ripken Sr.

As a youngster, Cal Jr. always wanted to be in the middle of the action, which is what led him to pitching in the first place. “When you’re pitching, you’re in control every pitch,” he said. “It’s the best place to be, but you can only be there once every five days.

“As a kid I was a catcher, because ‘Pops’ was a catcher and you always want to be like your dad, and that seemed like the second best place to be. But I stopped catching early, probably because the equipment was too big (obviously an early stage of his development). After that, shortstop seemed like the third best place to be.”

When it came time to make a decision, Cal Jr. distanced himself from the debate. “I pretty much stayed out of that,” he said. “When the colleges started coming around, Dad and I talked mostly about whether I was going to pursue a career in baseball. If I had the ability, the feeling was to get on with it and if it didn’t work out start over again in college at 25 or 26 instead of 18 or 19. I agreed with that. I was prepared to play.”

About a week before the draft, Bowie took Cal Jr. to Memorial Stadium for a private workout. “Dick, his son Randy, (associate scouts) Paul McNeil and Bill Timberlake and myself were the only ones there,” Gilbert said.

“I don’t remember how long it was before the draft, but Cal had about a week or 10 days to rest after his season ended. We had seen enough of him as a pitcher, and Dick liked his bat and wanted to see his arm from shortstop when it was fully rested.

“Clyde Kluttz (then director of player development) told Dick: ‘When you get finished, come up to the office and tell me whether he’s going to be a position player or a pitcher.’ ”

“I didn’t talk to any scouts before the draft,” Cal Ripken Sr. said. “When the Orioles drafted Cal Jr. (in the second round, fourth team pick overall) Tom Giordano (then the scouting director) asked me: ‘What do you want to do?’

“I told him it wasn’t what I wanted to do, it was what Cal Jr. wanted to do. He wanted to play every day.

“Had he been drafted by another team that would have been a stipulation before he signed. Our thinking was that if something happened, he could always go back to pitching when he was 20 or 21 years old.

“But if he started out pitching and didn’t hit or field for three or four years it would be difficult to go back to playing every day,” the Orioles’ third base coach said.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.