Pitzer Professor’s Course in Mathematics Is a Piece of Art

- Share via

Las Vegas card tables, the Parthenon and Picasso’s Cubist works cozy up to logarithmic spirals and the Pythagorean theorem in Jim Hoste’s classroom.

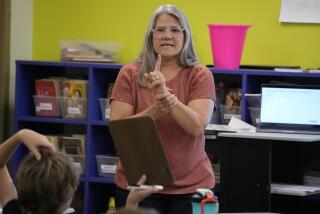

Hoste, a professor at Pitzer College, has dreamed up a class called “Mathematics, Art and Aesthetics” to crack the math phobia of many liberal arts students.

It’s not all pretty pictures, though.

“We cover very serious math in this course, a great deal of serious, beautiful and interesting math,” says Hoste, 37, who chairs the math department at Pitzer, one of the six Claremont colleges.

With more and more experts warning about math illiteracy in the classroom and America falling behind in science and engineering, Hoste provides a refreshing way for students to understand that math is everywhere.

Listen to 24-year-old Sandy Norris, who just graduated from Pitzer with a degree in psychology:

“When I took calculus, I thought, ‘This doesn’t really apply to my life at all.’ But when I took his class, it made me think about the world I live in, and I saw how it related. I’d go home and tell my roommates, ‘Wow, this is really interesting!’ ”

Hoste gets accolades from professionals as well.

“I think what he does is fabulous,” says Ken Millett, director of the California Coalition of mathematics, a nonprofit educational group that seeks to boost math aptitude.

“His program, his approach, is great. It’s just the sort of thing we need to have, not only in colleges but in our elementary schools as well, to help more people see math as something that’s useful and important.”

At Pitzer, a college known for its social sciences, Hoste has attracted students majoring in everything from film to psychology, art and, of course, math. His class fulfills a Pitzer requirement for a “formal reasoning” course, and little background in math is necessary, although high school algebra helps, Hoste says.

In his two years at Pitzer, Hoste has honed the curriculum, dropping a section on music and math, adding guest lecturers such as a computer graphics artist from Hollywood.

But some things are eternal. You can’t beat the ancient Greek Parthenon to help students comprehend a mathematical concept called the golden ratio.

“The Greeks were enamored by the golden ratio; they felt it was the prettiest rectangle,” Hoste says, explaining how the dimensions of the Parthenon reveal the concept.

The term golden ratio refers to rectangles of such proportion that when perfect squares are cut from them, smaller rectangles of the same proportions remain. This pattern repeats each time a square is cut away, leaving a progressively smaller rectangle. Hoste calls this a logarithmic spiral, which he says also occurs in nature.

He often sends students out foraging for examples of such spirals in sunflowers, plants or pine cones so they make the connection between math and naturally occurring forms.

Such links between seemingly disparate worlds were not always apparent to Hoste. There was a time when he probably would not have signed up for his own course.

“As a kid I ignored everything but math and science. I detested everything that had a vaguely humanities label,” he recalls.

When he learned to his dismay that he would need one year of a foreign language to graduate from college, Hoste settled sulkily upon French. He met his future wife in the class, and they took off for Europe one college summer. He was dragged to the Louvre, the Pompidou Center, the Prado and the Tate.

“Suddenly, I started seeing some of the world’s great artwork, but I still wasn’t that excited about it,” Hoste confesses. But memories of Braque, Monet and Gaugin kept filtering back, so he took an art class at UC Berkeley, where he enrolled after he returned.

“Between going to Europe and taking that class, I just got hooked. Now I really like to go to art museums. I also found that the deeper I got into math, the more I started to think of it as more artistic and less scientific.”

Hoste says he faces the same challenge most college math professors do today: Few students are well-prepared or consider mathematics as a vibrant field of study.

So Hoste employs a bag of tricks that includes having students read “Flatland,” a 19th-Century science fiction novel by Edwin Abbott about two-dimensional creatures who have an encounter with a three-dimensional being.

Although the book is ostensibly a social satire, it also gets students pondering such serious mathematical concepts as space and dimension, Hoste says.

Other tools include graphic works bC. Escher. “I don’t consider him a particularly great artist, but his pictures were very mathematical,” Hoste says.

Students who enroll in hopes of an easy “A” are disappointed to learn how much homework and problem-solving accompanies all this art. In fact, Hoste says, he has received complaints that the course is too rigorous.

But Kathie Richter, a math major who took his course as a junior at Pitzer last year, came away dazzled.

“A lot of it was very sophisticated math, and he was able to present it in such a marvelous fashion that I was able to retain and use a lot of it in other classes,” Richter says.

Even the flyer that he passes out to pique student interest is unorthodox: Hoste titles it “The Mathematics Mystery Tour,” and to read the course description, students have to construct the flyer into a model of a Mobius strip.

“It won’t be your standard math class,” promises Hoste, who sprinkles his conversation with references to Salvador Dali, French pointillist Georges Seurat, hypercubes, knot theory and topology--the study of the properties of geometric figures that remain unchanged even when distorted.

Hoste received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees from UC Berkeley, and his doctorate in math, with an emphasis on topology, from the University of Utah.

Before coming to Pitzer, his studies included a year at the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences at New York University, where he was a National Science Foundation post-doctorate fellow. He was an assistant professor at Rutgers University for three years.

Princeton University mathematician William Thurston, a nationally known topologist, says Hoste epitomizes a growing trend toward relating math principles to daily life and nature.

“There is a movement to try to make mathematics less abstract and threatening and more directly relevant,” Thurston says. “What (Hoste) is doing sounds great. I approve of his approach.”

Both men believe that math does not necessarily have to be learned in a traditional fashion. Thurston says math is usually taught “like a long skinny palm tree. You climb up till you lose your grip and fall splat on the ground.”

But he and Hoste believe that math education should be more like a banyan tree, which has multiple trunks and low branches where the intrepid can gain toeholds.

“I use the art as a kind of window,” Hoste says, adding that the students examine the angles of a Cubist painting or slap down cards to calculate blackjack odds without even realizing they are doing math.

For Hoste, however, art has provided a window back into math.

“I feel like I’ve gone on an incredibly long journey and come full circle,” he says. “I started out thinking that art and math were at opposite ends, and now I realize there are gigantic ties, because when you do math, it’s a lot like fine arts.

“There’s a tradition and a framework and structure that you work with, but you’re creating new stuff and experimenting.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.