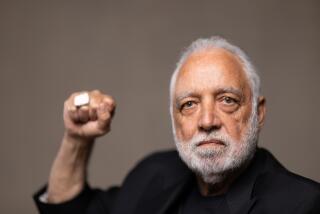

C. Garry, 82; Attorney for the Black Panthers

- Share via

Attorney Charles Garry, a self-styled courtroom “street fighter” whose clients included leaders of the Black Panther Party and the Rev. Jim Jones, head of the People’s Temple cult, died Friday in a Berkeley hospital. He was 82.

Garry suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage at Alta Bates-Herrick Hospital after he was admitted last Sunday for a stroke, spokeswoman Carolyn Hemp said.

During a legal career that spanned nearly six decades, Garry first worked as a labor lawyer before earning a reputation as a defense attorney with a penchant for tackling civil rights cases and representing clients with unpopular causes.

In the 1950s, he defended targets of McCarthyism. In the 1960s, he defended students who clashed with police in San Francisco City Hall outside meetings of the House Committee on Un-American Activities.

Later, Garry represented a group of young draft resisters known as the Oakland Seven and several San Quentin prisoners accused of murder during a 1971 prison riot. He also defended Vietnam War protesters as well as members of the militant Black Panther Party on charges ranging from assault to murder.

Garry represented Black Panther leader Bobby Seale, one of the Chicago Seven, the group charged with conspiring to disrupt the 1968 Democratic National Convention.

Garry defended another Black Panther leader, Huey P. Newton, in a murder trial in which he relied on a novel strategy at that time--asking that the indictment be quashed on the grounds that the jury selection process was unfair.

With the help of psychologists, Garry argued that blacks and other minorities were systematically eliminated from juries, leaving all-white panels that could not be impartial when a black was on trial. Although he failed to win his argument at the time, Garry’s strategy was widely copied by other defense attorneys.

One of his most infamous clients was Jones, founder of the People’s Temple cult. As Jones’ attorney, Garry was in Jonestown, Guyana, in 1978, when Rep. Leo J. Ryan was assassinated and more than 900 of Jones’ followers died after drinking cyanide-laced fruit punch. Garry escaped the mass suicide-murder by fleeing through the jungle.

Years later, Garry said he was still haunted by the betrayal of Jones and the violent end to what he thought was a paradise free from racism and sexism.

In 1988, when Garry was honored by the California Attorneys for Criminal Justice, Tom Nolan, the president of the 2,000-member organization, lauded his colleague’s compassion for the underdog. “I’ll never forget how he taught us it’s OK to shed tears at closing arguments, to push the envelope,” Nolan said.

Garry, the son of Armenian immigrants, was born in Massachusetts but grew up in California’s rural Central Valley, where he said he was harassed because of his ethnic heritage. That prejudice, he said, led him to speak out against racial discrimination.

Garry, who shortened his given name--Garabed Garabedian--put himself through night law school while working as a union organizer. He graduated from San Francisco Law School in 1938.

In 1957, Garry was called before the Un-American Activities Committee and asked if he was a communist. Citing the 5th Amendment, he refused to testify.

“I don’t belong to any organized Marxist party,” he said later. “I adhere towards the means of production to be in the hands of the people.”

Garry, who was in the Army during World War II, saw service in Europe. He is survived by his wife, Louise, whom he married in 1932.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.