The Ponce of Players : PLAYING THE GAME, <i> By Ian Buruma (Farrar, Straus & Giroux: $16.95; 234 pp.)</i>

- Share via

Ian Buruma’s “Playing the Game,” an epistolary biography masquerading as a novel, is a honeyed account of the life of that dazzling orchid in the English imperial garden, His Highness the Jam Saheb of Nawanagar, Col. Shri Sir K. S. Ranjitsinhji. The English sporting public, dispensing with the Oriental flummery, dubbed him Ranji, and Ranji he has always remained.

Until he stepped onto the playing fields of Queen Victoria’s last years, there had never been any such thing as an Indian cricketing virtuoso, for the English modestly assumed that because they had invented the game, it would remain forever their own private preserve. In Ranji’s day, cricket was assumed to be white, English and Christian. Ranji was born brown, Indian and Hindu. What compounded his sins was that his style of play was as alien as his origins, hence the remark of one of his exasperated contemporaries: “He never played a Christian stroke in his life.”

Buruma, who is known for his journalistic writing on Asia, starts out as a cricketing chronicler under the grave handicap of being Dutch. He has written the conventional story of Ranji’s life, portraying a garish grandee who scattered gold cigarette cases and guinea pieces among the professional cricketers, who threw sumptuous shooting parties, who flaunted his jewels, and who made countless speeches at countless London dinners, where, under the drifting cirrus clouds of cigar smoke, he told the English what they wanted to hear: that India would always be loyal to what was once laughingly known as the Mother Country.

It is a pretty tale to which the entire population of Britain always has subscribed--until just the other day, when Buruma had the atrocious luck of seeing the mild-mannered ironies of this, his first novel, upstaged by a new startling biography of Ranji, just released in England (“Ranji: A Genius Rich and Strange” by Simon Wilde), which paints a very different portrait.

It seems that the real Ranji was only a pretender to the throne of Nawanagar who acquired the succession through long years of ruthless intrigue and lying; there are even faint suspicions that he may have been behind the assassination of his chief rival for the crown. As for his triumphal march through English society, Ranji left the road strewn with bad debts and outraged creditors, begging letters and misleading statements. To do Buruma justice, at the end of the long letter purportedly written by Ranji to an old friend, there are one or two delicate intimations that the great prince may have been not much more than a great ponce, but the effect is not to clarify but to smudge all the important issues.

Buruma no doubt thinks he has written a comic book, a gentle, affectionate spoof at the expense of a man who tended to take himself too seriously and whom posterity has taken as sort of a mystic visitation from the pages of Kipling. If this is so, then his judgment is sadly at fault, particularly with reference to the Gilbertian events surrounding Ranji’s time as representative of the Indian princes at the League of Nations. Here is one of the great comic set pieces of modern imperial history, and the author ruins it by pretending it was all a joke:

When Ranji went to Geneva, he took with him his cricketing comrade and close friend, Charles Burgess Fry, soccer player, cricketer, one-time holder of the world long-jump record, gifted academic and classical scholar, novelist, parliamentary candidate, the very flower of the Corinthian tradition. Fry was serving as Ranji’s secretary and speech-writer when a convocation of Albanian bishops, touting for a monarch, offered Fry the throne of their country if only he could find 10,000 a year to buttress his regality with a touch of opulence.

At first, Ranji pledged the money, and posterity always has assumed that he later withdrew the offer because he valued Fry’s company too highly to sell him off to a bunch of Albanian clerics. The latest biography tells us that Ranji could no more have found 10,000 than he could have bought an eye to replace the one he lost in a shooting accident. But just for a moment, with an English hero about to ascend a foreign throne, life took on the contours of an iridescent Ruritanian bubble. No richer farce ever found its way into the footnotes to the history of the British Empire. This is what Buruma makes of it, when he puts these words in Ranji’s mouth:

“The Bishop, far from being an Albanian man of the cloth, was in fact my jeweler in Geneva, whose knowledge of emeralds and diamonds rather surpassed his acquaintance with Albanian affairs. I hope you can forgive me for my little jest.”

And I hope we can forgive Buruma for his.

It would be interesting to know what audience he hoped to find. The knowledgeable student of cricket history may well lose patience, as I did. Those who care nothing for the game, and know even less, may be bored if they are English. But what is really very puzzling is why anyone should have assumed that American readers would be able to make anything of it. I assume that their bewilderment in the face of the cricketing life will be roughly akin to my own as a child when taken to see a dreadful Gary Cooper film in which he portrayed a star baseball player who dies prematurely.

The writing is elegant in some places, but what use is elegance when it is inscrutable? The problem of selling cricket to Americans was illustrated to perfection two generations ago when P. G. Wodehouse planted one of the characters in “Piccadilly Jim,” an American tycoon with a social-climbing wife, at a big cricket match. The poor mutt is not only unable to understand what the cricketers are doing but cannot even make sense of the reports of the game in the following day’s newspapers. I fear that this may well be the dilemma faced by American readers of “Playing the Game.” You have to know about cricket history to be able to follow it, and if you know about cricket history, you wouldn’t wish to follow it.

Not only has Buruma written the wrong book but he has published it in the wrong continent.

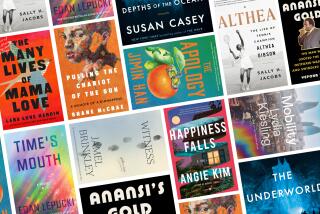

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.