COMMENTARY : Success in Yankee Clubhouse Will Be Vital for Showalter

- Share via

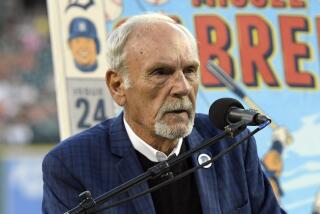

NEW YORK — The Yankees re-introduced Buck Showalter Tuesday, as much to themselves as to the media. Showalter was dismissed as a coach Oct. 7 and then hired as their manager 15 days later, with the formal announcement saved until the completion of the World Series. Only the Yankees can make such comebacks possible.

General Manager Gene Michael had disqualified him from his managerial search, both individually and categorically. He did not want a rookie manager. And then Tuesday he made it a point to pronounce he was “100 percent behind” Showalter.

When someone asked Michael if this were his first choice, Michael replied, “It is now. That’s the best way to put it.”

All this put Showalter in a potentially embarrassing situation. But Tuesday, in his first day on the job, he showed that he could manage a sticky mess, which is not unlike managing the Yankees. He did a fine job of damage control.

Showalter, 35, said he thought Michael was “doing me a favor” when he told him he might want to look for another job and that he understood Michael came back to him because “he didn’t find the qualities he was looking for in others.”

The new manager looked his questioners straight in the eyes, addressed the familiar ones by name, revealed assuredness in his voice and displayed a dry, deprecatory sense of humor.

When a reporter asked him about the team policy on long hair, a triviality that doomed his predecessor, Showalter answered, “I stopped by the barber shop yesterday just to be sure.”

He made an impressive package. The Yankees came up with an intelligent baseball man, a dedicated worker and, as evidenced by the recent player support for him, a likeable guy. But a good manager? Who knows?

The real test for Showalter is how he handles his clubhouse. Managing has become less a matter of running a game and more a matter of juggling egos. Inherent respect for authority has dissolved everywhere in our society. There is less reverence from children for teachers, citizens for policemen, and million-dollar ballplayers for managers.

Showalter, older than some of his players and good friend to some others, must win their respect, not just their friendship. It never happened for Stump Merrill. Players formed an anonymous mutiny against Merrill, even imploring reporters it was “your job” to get him fired.

“The best part, the easiest part, is the game itself,” Showalter said. “That’s the part that you look forward to. The other part makes or breaks managers. You have to create a positive atmosphere in the clubhouse. How do you go about that? There’s no set recipe. I like to treat people with honesty and humanity.”

He has a fine record as a minor-league manager, winning almost 64 percent of his teams’ games. But Showalter has never managed above the Double-A level. He has managed players who are hungry in every sense of the word. Motivating players with incentive clauses, arbitration rights, guaranteed long-term contracts and pet cougars is another task altogether.

His diligence as a coach is no indication; that job is not a predictor for managing, either. Mets General Manager Al Harazin, after watching Bud Harrelson fail at that transition, called it the difference between living on Earth and Mars, apparently with the manager’s job being the planet with the hostile environment closer to the heat source.

There will be more pregame meetings next year, Showalter said -- meetings to study the other team clear down to their last relief pitcher. The idea is to have them prepared for every game. If the work also enhances the manager’s authority, well, that’s a nice side benefit.

“If you can’t be organized and detailed yourself,” he said, “you can’t expect your players to be that way.”

Showalter’s first job is to clean up the mess left over from the Merrill mutiny; he knows that. It already is on the agenda for the first day he gathers his team in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

“There’s a lot of good attitudes here, too,” he said. “The first thing you have to do is set a tone in spring training. A lot depends on spring training. It’s going to be as important a spring training as any I’ve seen.

“If you set down goals and get after it, you can overcome potential problems. You can’t just sweep them under the carpet and say they don’t happen. We’ll address them.”

Showalter arrived at this position under bizarre circumstances, something he himself as much admitted when he recounted when Michael called him Oct. 19 to talk about the managing job. Showalter was so flabbergasted by the turn of events that “there was a long silence” from his end of the phone, he said.

Michael, realizing Showalter’s surprise, said, “I’ll tell you what. I’ll call you back in 10 minutes.” Three days later -- 15 days after Michael suggested he check out employment elsewhere -- Showalter was manager of the Yankees.

In a roundabout way, the Yankees appear to have made a wise choice, even if the one-year contract contradicts Michael’s announcement that “the main reason is the potential that he has.”

Showalter has this firm manner about him without being the least bit overbearing. He makes you think you could trust him with delivering one fresh egg clear across the city -- his grip firm enough never to drop it yet soft enough not to crush it. But then the Yankees, like every team, have some bad eggs. His success in his new job depends on how he manages them, not so much the ballgames.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.