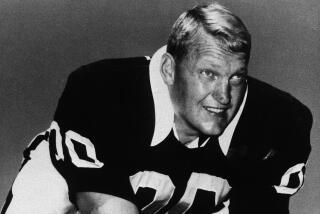

Lyle Alzado Is Dead at 43 of Cancer : Football: The former Raider succumbs to a rare brain lymphoma that he said was brought on by use of steroids.

- Share via

Lyle Alzado, a big, wild, talented, mean guy on the football field, whose intimidating style wreaked havoc on opponents and made him an NFL legend, died Thursday at his home in Lake Oswego, Ore., near Portland. He was 43.

His wife, Kathy, was at his side. He had been undergoing chemotherapy for brain cancer--he blamed his steroid use during and after his playing career for the illness--at the Oregon Health Sciences University Hospital.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. May 16, 1992 For the Record

Los Angeles Times Saturday May 16, 1992 Home Edition Sports Part C Page 7 Column 1 Sports Desk 1 inches; 15 words Type of Material: Correction

Alzado--Marcus Allen’s rookie NFL season was 1982, rather than 1983, as reported in Friday’s editions.

Alzado was a star defensive end in the NFL for 15 seasons but may be best remembered for his four years with the Los Angeles Raiders, where he retired after the 1985 season. His fierce style of play seemed to epitomize the Raider philosophy.

Alzado used to say, “If me and King Kong went into an alley, only one of us would come out, and it wouldn’t be the monkey.”

But off the field, many who knew Alzado say he was the gentlest of men and will be remembered for his kindness and generosity.

His continued use of steroids, however, might have heightened his aggressiveness off the field as well as on. He was involved in several well publicized off-field altercations after his retirement, one with a motorist who accused him of brandishing a gun, another with a female deputy marshal who said he attacked her when she tried to serve papers on him.

Alzado, who used his football fame to get into acting, married fashion model Kathy Davis in March of 1991, and was told a month later that he had inoperable brain cancer. By the time he died, he had lost nearly 100 pounds from his once-intimidating frame.

Alzado underwent treatment at UCLA Medical Center for a year before moving to Portland with his wife to live close to her family. While in Oregon, Alzado underwent an aggressive form of chemotherapy treatment that resulted in a long siege of pneumonia.

Alzado’s cancer was a rare form of an already rare type of cancer, a primary brain lymphoma. Cancer usually begins in the body’s lymph system, but his started in his brain.

Alzado said he began using steroids to bulk up when he was at Yankton College in South Dakota and continued using them, as well as the human growth hormone, well beyond his NFL career.

“I had my mind set and I did what I wanted to do,” Alzado said about his steroid use. “So many people tried to talk me out of what I was doing and I wouldn’t listen.”

For a few months in 1991, Alzado’s cancer went into remission after radiation and monthly chemotherapy treatments. But it came back near the end of the year and was layered over nerves in his spinal column, causing him severe pain and making it difficult for him to swallow. His speech was raspy, he talked with a slight lisp, and he needed help in walking.

Still, Alzado remained positive about beating the disease.

“You can never give up,” he said in January. “Giving up is the worst thing you can do.”

Twice a week he was taken to UCLA for chemotherapy sessions. The cancer went into remission again in February, but that period of remission was shorter and he and Kathy decided to move to Oregon.

A few days before Alzado left, about 200 of his friends and former teammates held a tribute for him at a hotel near LAX. Alzado could barely speak, but he didn’t stop smiling the entire evening.

Former Raider teammate Marcus Allen presented Alzado a full-size sculpture of him by artist Bill Mack, showing Alzado victoriously holding a piece of an opponent’s jersey. The piece will be displayed in the NFL Hall of Fame.

When he was escorted to the stage to speak, Alzado turned toward the table where Raider owner Al Davis was seated.

“Al, I love you,” he said.

It was Davis who resurrected Alzado’s career and turned him into a Los Angeles celebrity. In 1982, the Raiders first year in Los Angeles, Davis traded a late-round draft pick to the Cleveland Browns for Alzado, who at the time was a seemingly washed-up defensive end.

The Raiders had a young, talented defensive end, Howie Long, and thought Alzado could help groom him. They also had John Matuszak and Ted Hendricks, other wild guys. Alzado, who grew up street-fighting his way though the slums of Brooklyn and, later, Long Island, fit in beautifully.

“I should have played my whole career as a Raider,” Alzado said. “When I got there, I was at the end of my rope; my career was about done. Al Davis and Tom Flores, who was the greatest coach I ever had, and Earl Leggett, sat down and put their arms around me and said, ‘We know you can do this job, now just show us.’ And when I did, that’s all I needed. I was a star ever since.

“It was like starting over, because Al Davis and Tom Flores did things for me that at other clubs, I didn’t get the opportunity to do, such as play the way I felt comfortable playing. . . . It was everything football should be.”

Alzado played eight years for the Broncos and three years for the Browns. When the Raiders traded an eighth-round draft pick to the Browns for him, he was embarrassed. He was used to being thought of as worth more than an eighth-round choice.

As Denver’s fourth-round draft choice in 1971, Alzado started and played in 66 of 68 games before he suffered an injury in 1976. He was a member of Denver’s “Orange Crush” defense and in 1977 was voted defensive lineman of the year and a Pro Bowl starter. When Denver traded Alzado to Cleveland, the Browns had to part with three high-round draft choices.

At Denver, Alzado’s role model was Rich (Tombstone) Jackson, who Alzado says might have been the best defensive end he ever saw. But Alzado never felt that he fit in at Denver and was happy to leave. He said he enjoyed Cleveland, but found his real home in Los Angeles.

His first day at Raider practice, though, Art Shell decided to let him know exactly what kind of team he was with. He lined up across from Alzado, picked him up and dropped him flat on his back.

“I thought to myself, ‘Am I on the right team?’ ” Alzado said.

As things turned out, he was. Alzado immediately took his place at defensive end, buckled on his helmet and went to war. He quickly grew close to Shell, Gene Upshaw and Long, who used to eat at Alzado’s house almost every other night.

But Alzado had a soft side that was seen more by children than adults. He had graduated from Yankton College with a degree in special education and visited children in hospitals and at charity functions each week of his NFL career. That gentleness finally was seen by millions on television in the closing minutes of the Raiders’ Super Bowl victory over the Washington Redskins at Tampa in 1984, when tears streamed down Alzado’s cheeks.

In that game, the Raiders had built a 21-3 lead by halftime and maintained domination throughout. Alzado ate up Redskin tackle Joe Jacoby, and Marcus Allen, then a rookie, rushed for 191 yards and scored two touchdowns, earning the MVP award.

After the 1985 season, Alzado, 36, retired from football and pursued his acting career. By that time, he was doing national television commercials and was a regular on “The Tonight Show.”

He made several movies and even had his own short-lived television series, playing a school teacher by day and a masked professional wrestler by night. But football wasn’t out of his system, and in 1990, Alzado, at 41, tried to come back with the Raiders.

He would be able to play again, he said, because of his “revolutionary training.” What it involved, however, was nothing more revolutionary than massive doses of steroids and injections of the human growth hormone. Later, he claimed that in the comeback attempt, he used a steroid that ruined his immune system and led to his cancer.

Hobbled by injuries throughout training camp, Alzado finally accepted retirement in late August.

“The uniform is retired, but time never stops for great people,” Davis said earlier this year. “Lyle was only here for four years, but people think of him as a Raider. I still get letters all the time from people who write that we need to have great teams again like in the 1960s and 70s when we had good players like Lyle Alzado and John Matuszak.”

Alzado is survived by his wife Kathy, a son, Justin, who lives with Alzado’s former wife in Long Island, N.Y., his mother, two brothers, and two sisters. His family plans a private service Friday in Portland.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.