The Endless Search : Unemployment: As the local economy sours, here’s how several Southern Californians are coping with being jobless for months at a time.

- Share via

Last year was going to be the year that Jim Benson paid off his credit card debt, put the rest of his personal finances in order and started shopping for a retirement home. Instead, 1991 was the year when he lost his job as a production planner at Lockheed Corp. in Burbank.

He’s been looking for a full-time job ever since, an odyssey that has lasted 18 months. For a proud man who expected it to take four months, at most, to find work, it’s been a tough haul. He has sent out 400 to 500 resumes but, except for landing a temporary, part-time job, it’s been for naught.

“If I didn’t have a sense of humor and, more important, family support, I’d probably be bonkers by now,” said Benson, a stocky 52-year-old with a gravelly voice.

Benson belongs to California’s deepening ranks of long-term job hunters--victims of the national recession and structural economic shifts in the state that are putting people out of work and keeping them on the street longer and longer.

For most, the job search is an exasperating experience. “Jobs will just disappear. A company will decide to hire somebody, and then they just don’t,” said Pat Lowenstam, a 45-year-old personnel executive who landed a job with a Carlsbad firm last month after a wearying 14-month search.

“Relatively few people are ready for so many ‘No’s,’ ” added David H. Hendon, manager of a job placement and retraining center in Burbank. “If their self-esteem already is fragile, this just heaps it on.”

The California recession, running deeper than the nationwide slump, casts a long shadow over far more than just the job market. The state is battling a fiscal crisis, the residential and commercial real estate markets are in the midst of a long-term slump and the aerospace industry, a longtime mainstay, is shriveling because of defense spending cutbacks.

But probably no one feels the pain more acutely than long-term job hunters, who have to keep motivating themselves to comb through the want ads, work the phones and mail out resumes to find work.

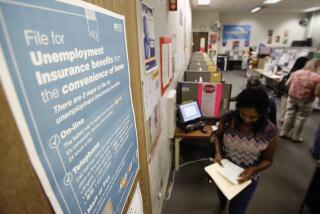

Some people get so embarrassed that they avoid their friends and neighbors; others get so desperate that they practically beg for jobs. Meanwhile, most live off their savings, financial help from family members and unemployment benefits--if they are lucky enough to qualify for the benefits and haven’t exhausted them yet.

The growing misery is reflected in government statistics: The number of Californians out of work 27 weeks or more totaled 342,000 in August, more than double the level of a year earlier. The national figure also has risen, although not quite as dramatically, climbing 76% over the past 12 months to just over 2 million.

Yet these figures don’t even include the millions of people such as Benson who, by virtue of taking part-time jobs, are officially considered employed even though they also have been unsuccessfully seeking full-time jobs for months or more.

Also rising, though not as dramatically as the number of long-term unemployed, are the nation’s ranks of discouraged workers--people who say they want jobs but are so pessimistic about their prospects that they quit searching.

All told, most of the unemployed still cling to hope and continue to hunt for work, but “they’re just not finding jobs and they’re staying unemployed,” said James Medoff, a Harvard labor economist.

Medoff says a big part of the problem in California and nationwide is that lots of jobs have been eliminated permanently, both in the white- and blue-collar segments of the labor market, yet many of the unemployed apparently haven’t changed their career expectations. Some job seekers--including many laid-off aerospace workers--lack the training to find work of equivalent pay in other fields.

Among individual job hunters, long-term unemployment triggers varying reactions. Here are some of their stories:

Diana Moreno

After looking for a job in finance for most of the last 18 months, Diana Moreno knows first-hand how tough things can get when you are at the mercy of employers and executive recruiters. She has been belittled, badgered and misled--in short, she has gamely suffered the daily indignities of looking for work.

There was the time a recruiter insisted on interviewing her until 11 p.m. even though she had to be ready for three more job interviews starting at 7:30 the next morning.

At another firm, an interviewer derided her work experience, telling Moreno that as a longtime bank employee she didn’t know what job pressure really is.

Worst of all were the 10 or so times that she made it to the final cut of an employer’s screening process, only to lose out to someone else.

“It’s an emotional roller coaster,” said Moreno, 43. “You have highs when you get an interview, and lows when you don’t get the job. You feel as though you don’t have control over a situation.”

Still, her easy laugh has endured. “You learn to swing with it,” Moreno said. “It’s disappointing, but life goes on.”

Nothing in Moreno’s background prepared her for the rejection that comes with long-term unemployment. Her resume is filled, as she put it, with “big-name schools and big-name companies.”

A lifelong Angeleno, Moreno attended Birmingham High in Van Nuys, where she was friends with Lowell Milken, the younger brother of convicted junk bond wizard Michael Milken. (She says she is puzzled by Michael Milken’s hard-driven public image, remembering him as “extremely nice, extremely popular and extremely friendly.”)

Moreno earned a bachelor’s degree in anthropology from UC Berkeley, taught fifth grade for a year, then got a master’s degree in business at UCLA. Eventually, she landed at Security Pacific, where in 11 years she worked her way up to senior vice president in charge of financial information.

But in 1989 her job was eliminated. After nine months of joblessness, Moreno went to work for the law firm of O’Melveny & Myers for 18 months, managing such tasks as the construction of a branch office.

When the construction project ended, her job was over. She left the firm in March, 1991, and other than a temporary job with the tax preparation firm H&R; Block, has been out of work since.

It’s taken a heavy toll on her net worth. Moreno says she has burned through $50,000 in savings. She is selling her Mediterranean-style house in the Hollywood Hills, which she extensively remodeled over the past two years without the help of a general contractor.

Moreno isn’t fretting about the house; she says giving it up will make it easier to be flexible in her job hunt. Moreno, who is single, says she will go wherever the right job is.

Meanwhile, Moreno said she has learned to deal with the disappointments of looking for work by developing other interests. To keep job hunting from taking over her entire day, most afternoons she takes walks of four to six miles.

She reads mysteries and bones up on tax law. On an unpaid basis, she works two days a week at a nonprofit employment assistance group, Forty Plus of Southern California.

“You have to have other things you can achieve,” Moreno said. “Other things are just as important to me as the job search.”

Louis Fleeks

One year after being fired as an RTD bus driver, Louis Fleeks is living in a subsidized hotel room on Skid Row, trying to muster the motivation to look for work.

Fleeks, 38, is a trim, well-groomed and well-spoken man who looks out of place among the street people who are his neighbors. He talks of wanting to find a new job that will enable him to rejoin the economic mainstream.

But Fleeks has been slow to get started, applying at only three employers over the past year. At varying times over the past 12 months, a labor market economist alternately could have classified him as a discouraged worker, a dropout from the work force or one of the long-term unemployed.

Why hasn’t Fleeks been pounding the pavement? For the first few months he was in a drug rehabilitation program, concentrating on battling a six-year-long cocaine addiction, which Fleeks says cost him his job at the RTD. His efforts apparently have been successful; Fleeks says he has been off drugs since losing his bus driver’s job.

Yet in recent months, Fleeks says, his job search has been slowed by other demons--fear of rejection and welfare dependence. He says bad news about the economy has been demoralizing too.

“I have found myself getting lazy, not just physically but mentally. I’m losing the determination I had,” he said. “By being on GR (general relief welfare), you get used to doing nothing.”

“If I wasn’t on GR,” he added, “I’d be working right now.”

In fact, at other points in his life--even while he had a drug problem--Fleeks says he had little problem finding work. Before going to the RTD, he drove for a commuter bus line between Orange County and downtown Los Angeles.

His easy, outgoing personality apparently was a hit with his riders. When his company lost the contract to do the commuter run, one rider helped him get the RTD job.

“Everyone was crazy about him,” said Gerrie Dobmeier, another of Fleeks’ former riders. “He had something nice to say to everyone. He knew everyone by name.”

Dobmeier tells the story of a time she accidentally left her purse on Fleeks’ bus. When she got to work, she frantically began calling the bus company. But while she still was on the phone, in came Fleeks with the purse--he drove back to drop it off personally after finishing his route.

These days, Fleeks is painfully aware of how far he has fallen on the economic scale. For a while, he stayed off the streets at certain points during the day, out of fear that one of his former Orange County passengers would ride by and figure out that he was living on Skid Row.

For several months this year, he clung to hope that he would win a job as an assistant hotel manager for Single Room Occupancy Corp., the nonprofit group that manages the building he lives in and other hotels on Skid Row. But in July, Fleeks says, the job went to someone else.

“I don’t like the rejection,” he said. “When I look for a job, I’ve already researched it and have decided I would like working there . . . to be rejected from something like that, that’s a slap in the face.”

Still, he says he is certain there is work to be found, despite the slow economy. It’s just a matter of fighting for a position. “There’s always a job out there for people who are willing to work,” he said.

“I’ve had my break away from the economy. I want to go out and do something,” he added.

“I really don’t belong down here,” living in a subsidized room on Skid Row, he said. “I’m taking someone else’s spot. I’m capable of being self-sufficient. . . . This little vacation is ending.”

Dan Sison

His motorcycle recently was repossessed. He’s behind on his credit card payments. But Dan Sison is keeping his cool.

To be sure, six months of unemployment have been tough on his bank account. And the timing is lousy: Sison, 28, is planning to marry in April.

But when it comes to his personal finances and job search, he has yet to push the panic button. “Career and jobs are just one component of life. It’s the only thing that isn’t right” in his life now, Sison said.

It helps that Sison’s fiancee is providing emotional support and financial help, with earnings from her job as a customer service representative for a health maintenance organization.

At the same time, Sison is trying to avoid sinking into desperation and taking the wrong job. He made that mistake once before, when he accepted his last job selling packaging products such as boxes and tape. Sison was fired six months ago, after holding the job nearly two years, because he never achieved his sales quotas. As a result, his pay never exceeded his base salary of $25,800.

Sison liked the company he worked for, but says he had a hard time getting enthusiastic about its products. “How do you get excited by a box?” he asked.

For now, Sison is focusing on marketing jobs at record companies and other entertainment firms. Marketing has been one his interests since he attended Cal State-Northridge, where he served a term as president of the Student Marketing Assn. But Sison has found the going tough in the job market, often losing out to more experienced applicants willing to accept less money than they made in their last jobs.

Currently, he’s waiting to hear if he’s been accepted into a management training program at a major movie studio. He also is beginning to look into hotel and retailing jobs.

“I’m getting less picky,” he said, “but I still have options.”

Sison, whose late father was a prosperous businessman and judge in the Philippines, never had a hard time making money before. As a boy, he delivered newspapers and mowed lawns.

In college he worked at a computer shop and a bank and ran his own business providing disc jockeys for weddings and parties. If he runs out of money, Sison said, he will resurrect his disc jockey business.

Despite his efforts to stay upbeat, there are moments when he begins to feel worn down by the job search, to which he devotes about five hours a day. “Being a sales representative, I’m used to no’s, but there’s only so much discouragement you can take,” Sison said.

Sometimes, he added, “you double-think yourself and you wonder, ‘What’s wrong with me?’ ”

Also tough on his self-esteem was applying for unemployment insurance, which brings him $350 every two weeks. “I’ve never been one to rely on someone else,” he said.

Perhaps worst of all are the mounting bills. Although he is living comfortably in a Woodland Hills apartment, Sison begins to lose some of his calm demeanor when the subject of debt comes up. “Everyone’s going to get their money,” he said of his creditors. “They’re just going to have to wait.”

Jim Benson

Until being laid off by Lockheed last year, Jim Benson says he never spent more than a week without a job. Before catching on at a Lockheed machine shop in 1978, he spent more than 20 years working at supermarkets, rising to the level of assistant manager.

It never was hard, Benson said, to switch from one grocery chain to another. “If you knew what you were doing, you’d just fill out an application, and they’d tell you they could use you,” he said.

Today, as Benson looks for jobs in manufacturing or back in the supermarket business, it’s another story.

He has trudged through industrial parks, visiting company after company to find out if they are hiring. He has dashed off dozens of letters to chief executives, hoping to impress them and get a leg up on other job candidates who simply submitted applications to the personnel department. He has attended job fair after job fair.

All he has to show for it is a six-week, part-time job passing out literature at a Mrs. Gooch’s Natural Foods store.

“Knowing how many people are out there looking, it isn’t much of a surprise,” Benson said. “There just aren’t jobs out there.”

“You go to a job fair now, and where you (once) stood in line for 15 minutes before waiting to see an exhibitor, you’ll stand in line 30 minutes now. . . . If you’re lucky enough to get an interview, you won’t be the only one there-- there’ll be a lineup of people,” Benson said.

Benson said he suspects that a big part of his problem finding a job is his age, 52. No employers actually admit they consider him too old, but Benson often is told he is overqualified, which he considers code language for the same thing.

“I’m tired of hearing the words ‘you’re overqualified,’ especially from some snot-nosed kid right out of college who doesn’t even know what the job entails,” Benson said, his voice rising with frustration.

Unemployment hasn’t been Benson’s only burden. Two months after he lost his Lockheed job, his wife suffered a brain hemorrhage and had to spend 12 days in intensive care. She is back home now, but still has trouble walking and difficulty with her short-term memory.

Most of the medical costs have been picked up by Benson’s health maintenance organization, but that coverage will end in November. Complicating matters further, Benson exhausted his $210 a week in unemployment insurance in July, and already has used up $15,000 of what had been $25,000 in retirement savings. Before his layoff, he had been earning $43,000 a year.

While Benson’s health generally is good, these days he isn’t sleeping as well as he did. He often suffers from indigestion, and he finds himself getting unusually tense while driving on the freeways.

To ease the tension and to take a break from job hunting, he occasionally takes what he calls an “attitude adjustment day.” When he can, he likes to watch trains climbing the Tehachapi Mountains on the winding stretch of track known among rail buffs as the Tehachapi Loop.

Benson also has attended group counseling sessions at an employment assistance center in Burbank, which he says gives him a chance “to blow off steam.”

And even though it will last only three more weeks, his part-time grocery store job provides a measure of satisfaction.

“It’s given me a little bit of my self-esteem back. It’s a job,” Benson said. “It gives me a sense of accomplishing something. I haven’t had that feeling in a while.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.