ARCHITECTURE : Pacific Bell’s Building Imprisons the Technology It Contains

- Share via

Where does the dial tone come from? Pacific Bell recently answered that question for me: Every time I pick up my telephone, they connect me to a building on the corner of Melrose Avenue and Crescent Heights Blvd.--where, deep inside the nearly windowless face of a four-story building, hundreds of densely packed gadgets click away to connect me to far-flung places.

Knowing where this happens doesn’t exactly remove the mystery, since the building doesn’t reveal much about what goes on inside. Built in 1955, it originally housed equipment four times the size of what is needed today to serve a vastly expanded network. Despite the Eisenhower-era optimism of its outward features, this switching station is out of touch with its own technology.

The nature of such equipment facilities frustrates any attempt to make them appear what they are. How do you express the miniature circuits and ephemeral waves that connect us all? Modernist architects once used steel and glass to represent the technology that was rebuilding our society. But in an age of miniaturization and etherialization, sweeping trusses and open expanses no longer speak of the nature of our society. Instead, we try to make new things look familiar, hoping to make their strangeness less frightening.

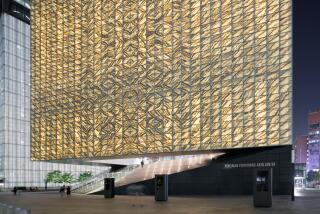

When architects Woodford, Parkinson, Wynn & Partners designed the building, they wanted to celebrate the new. The face of modernity here is an L-shaped panel of pinkish ceramic tile. Two thin bands of metal-framed windows accentuate its machined quality. The architects freed the facade from its traditional base, allowing it to hover over a line of metal exhaust louvers. Then they cut it loose by extending it over a recessed glass entrance box (now boarded up) on its western edge.

Two white-painted brick towers hold this abstract composition in place from behind. They rise to a full four stories, but at the top reveal themselves as nothing but more than thin planes.

On the eastern side, the building turns into a layered composition of brick and metal grating that seems to be buttressing the front. All these little games with thin planes free the building from its bulky reality, sending it sailing both down the slight slope of Melrose as it moves west and, metaphorically speaking, off into the future.

Reality unfortunately sets in on Crescent Heights Boulevard, where the switching station reveals itself in all of its bland weight. In the process, it brings the movement of the front of the building to a screeching halt. It is difficult to ignore how alien a structure this really is: Windowless and almost completely out of scale with its surroundings, it is an 88,000-square-foot mass that serves, but is not physically connected to, the neighborhood around it. The light and optimistic facade is only an image pasted onto a concrete structure that imprisons, rather than expresses, the complex technology it contains.

It may be impossible to represent modern technology in architecture, and it is certainly too much to ask of a 37-year-old building to speak to us of the excitement of the new. That this building puts such a good face forward is to its credit, especially since it creates a moment of complexity on the streetscape of Melrose Avenue. Here is an architecture that at least realizes the essential contradiction between the abstract nature of technology and the fixed reality of a building and allows that tension to slip out between its sliding planes.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.