A Look at Tylenol Poisonings--10 Years Later : Crime: The seven unsolved slayings had a far-reaching consequence: the tamper-resistant packaging on most foods and drugs sold today.

- Share via

CHICAGO — It’s been 10 years since seven people died from ingesting Tylenol capsules that had been laced with cyanide and placed on store shelves.

The slayings remain unsolved but the tragedy had at least one far-reaching consequence: the tamper-resistant packaging on most foods and drugs sold today.

“It all stems from that event,” said George Sadler, associate research professor of food packaging at the Illinois Institute of Technology’s National Center for Food Safety and Technology.

“It has changed the whole way the pharmaceutical industry and the food industry do business,” he said late last month. “Certainly, the added safety to public health has given some meaning to the deaths.”

The deaths led to tough criminal penalties for illegal tampering with consumer products and inspired federal regulations that require protective seals over non-prescription drugs.

The first of the Chicago-area victims was a 12-year-old girl, who died Sept. 29, 1982. By Oct. 1, six more people had died after taking tainted Extra-Strength Tylenol.

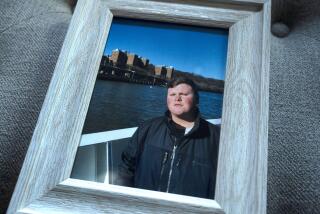

James W. Lewis, an out-of-work accountant, was never charged with the killings but was a prime suspect and was jailed on a related extortion charge.

Now 46, he is serving two, consecutive 10-year terms at the federal prison in El Reno, Okla. He was arrested after he sent a letter to Johnson & Johnson, the parent company of Tylenol manufacturer McNeil Consumer Products Co., demanding $1 million “to stop the killing.”

Lewis, who is up for parole in July, 1993, and whose mandatory release date is June, 1996, maintains his innocence.

In a telephone interview late last month , Lewis said, “I could have written a letter to the Roman Senate and asked for a million pieces of gold, but that would not make me the assassin of Caesar.”

He called the perpetrator “a heinous, cold-blooded killer, a cruel monster.”

Tom Schumpp, the state police officer who headed the investigation, said late last month that “the vast majority of the people who worked on the case believe that he was the killer, and I felt very strongly that he was.”

Schumpp, now deputy director of the state police’s Division of Criminal Investigation, said the Tylenol file consists of 20,000 pages. The task force he headed started with almost 100 officers and ended with six state police officers and six FBI agents who worked full time on it for 15 months.

“This was the kind of incident you really couldn’t protect yourself from,” he said. “The mere act of shopping and purchasing what we view as an innocuous and over-the-counter drug caused the deaths.”

Richard Ward, a criminal justice professor at the University of Illinois-Chicago, said the killings contributed to the growth of police intelligence systems.

“We’ve been using surveillance since the beginning of times” to track down people making threats and demanding money, said Ward, a former New York detective. “But in the last 10 years all forms of surveillance have increased dramatically.”

Sadler said nothing is really tamper-proof: Broken seals merely warn consumers.

“You cannot eliminate the threat 100%,” said Greg Erickson, editor of Packaging, a suburban trade magazine. “You can reduce the threat to some extent. Certainly unpackaged goods and produce are still susceptible.”

Ward agreed, saying: “Anyone who is crazy enough to put poison in food is likely to get away with it, at least initially.”

But he said the packaging and tracking improvements have increased the probability of tamperers being arrested. “Hopefully, that would be the deterrent,” he said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.