Hyperion Design Merits More Than Second-Class Treatment

- Share via

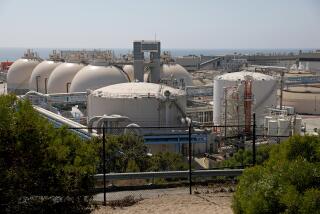

What is the shape of sewage? If the Hyperion Waste Treatment Plant is anything to go by, it is something between a spaceship and an Egyptian tomb. Millions of tons of sludge (or biowaste, as the sanitation engineers now like to call it) are encased in rolling bulges of concrete propped up by splayed, bunker-like walls.

This is an abstract monument to the constant struggle to hold the line against the tide of sewage that threatens to inundate our waterways and bays. This is 1990s heroic architecture: No kings or battles are commemorated here, only waste.

The Hyperion plant is one of the largest pieces of industrial architecture in Los Angeles. It sits on 144 acres of dune land overlooking the Pacific Ocean just south of Los Angeles International Airport along Vista del Mar at Imperial Highway.

There is something large scale about the whole neighborhood: To the north there are the giant hangars, runways and terminals of LAX, and to the south loom the Scattergood Steam Plant of the Department of Water and Power and an adjacent Edison Co. electrical generating plant, each one bulging with pipes, smokestacks and mysterious metal boxes. Here at the very edge of our city, its true industrial nature shows like a layer of sediment exposed by an earthquake.

A great deal of heroic work goes on here. Raw sewage comes into Hyperion from all of Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley, is processed through “bar gates” housed in a simple concrete volume, sifted, aerated and then finally pumped out into the ocean.

By 1998, Hyperion will have a “full secondary” capacity, meaning that the sewage will come out as close to clean water as possible.

For the past 15 years, the architectural firm of DMJM has been trying to give shape to this labor. The architects have lined Vista del Mar with a sloped warehouse rhythmically cut into sections, a parking garage whose concrete skeleton has been contaminated by the rounded shapes around it, the simple bar gate building and, my favorite of them all, a pumping building whose bowed front puffs itself out to send the sewage spewing five miles out into the ocean. A bridge resembling a ray gun connects the plant to a parking lot across the street, and soon cylindrical tanks will loom up from behind this more or less civilized row of structures.

The most expressive and most recent building, a yellow and green painted tube that produces oxygen, is actually hidden in the back of the plant. Its appearance makes me hope that the newer buildings will be better than those the firm produced in the past.

As I drove around Hyperion, I was struck by the contrast between the elegance and confidence of the streamlined buildings of the 1930s and the largely lumpen concrete containers constructed in more recent years. Under Tony Lumsden, the chief designer at DMJM, more expressive forms are starting to again inject some pride into this messy landscape.

Although it has its better parts, Hyperion in its entirety is something of a mess. Perhaps that is appropriate, but you still wonder whether we can’t come up with a grander, more clearly stated architecture for this huge public works project. If waste and its processing are such an important part of our society, we should be able to design forms that express this Stygian task, rather than retreating into compromises between suburban office park design and the raw power of an industrial plant.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.