The Search for DeMille’s Lost City

- Share via

If this were a movie it would be called “The Long Search for the Missing Egyptian Treasures of the Lost City of Guadalupe.”

Make that “Guadalupe” as in California, up the coast and just a tidal surge north of Santa Barbara.

Obviously, though, this isn’t a movie. But it is about a movie, an ancient (1923) movie. And an ambitious (cast-of-thousands) project and one man’s long (10-year) search.

Peter Brosnan is a 40-year-old Silver Lake filmmaker and documentarian who hopes he can take one of Hollywood’s current projects du jour-- preservation and conservation of old movies--in quite a different direction.

He wants to save a set.

Let others go looking for lost reels or faded negatives or tossed-away outtakes. Others can take old movies, enhance and hype them, stage premieres and peddle the restored version at the video store.

Brosnan wants only to save a set . . . and a tangible artifact of Hollywood history.

To Brosnan this is a special set, not one of those that in the great tradition of pillage and waste gets tossed away after the final loop. This was Cecil B. DeMille’s 800-foot-wide, 120-foot-tall mammoth set built on the sands of Guadalupe for his first and silent version of “The Ten Commandments,” one that had four 35-foot-high statues of the Pharaoh, Ramses the Magnificent, 24 five-ton sphinxes along with enough statuary and bas reliefs to supply a Rose Bowl swap meet for another 70 years.

If you want some sense of what Brosnan has set out to do, program your VCR for Saturday, 4 a.m. Correct: 4 a.m. That’s the time the American Movie Classics cable channel has scheduled, as part of its weekend Film Preservation Festival, DeMille’s “Ten Commandments I,” in very early Technicolor.

Almost all of the Egyptian set--considered one of the largest ever built of concrete and plaster--ended up under the sands of Guadalupe, deliberately buried in long, deep trenches, embalmed Hollywood style.

Maybe there were money problems--the film cost $1.4 million before burial and at one time the project was almost scuttled--and DeMille may not have had funds to dismantle and ship the sets to comply with his contract with the land owners.

Another theory about the monumental burial was that DeMille was concerned that competing filmmakers would use his sets and bring out their biblical epics before he could if he didn’t get rid of them.

The sets were buried, according to documents found by Brosnan and DeMille’s own indications in his autobiography.

So, what’s left in the sands of Guadalupe . . . and why bother?

Why bother, first.

It’s history, says Brosnan, a prelude of sorts to where we are now, morning in Hollywood. It’s the art of a period, a real piece of the American filmmaking pie. His idealism and certain dedication seem refreshingly real.

What’s left out there? Until a complete and proper archeological dig is done, no one knows for sure. The sands, according to some experts, have served as a preservative, although there has been some leaching of plaster caused by dampness. John Parker, who has been the chief investigator of “The Ten Commandments” site, believes a large part of the original set still exists. Ground radar readings confirm that materials lie below the shifting dunes.

Brosnan first heard about the “lost city” 10 years ago from a fellow filmmaker.

A hiker, he was familiar with the terrifying terrain of the Guadalupe dunes and he began to investigate the territory and gather material on what DeMille had done there. On his first visit, he and a companion spotted a thick plaster-of-Paris head where the wind had cleared some sand.

“The first time I was there it was a cold, dark morning on those isolated dunes. It was eerie,” he says. “There had been heavy rains and wild weather. Some of the set had been uncovered. It was like finding something historic, but with a definite Hollywood twist.”

He has shot almost 30 hours of film and taped interviews with former movie crew members, local residents, officials, DeMille family members. He’s hoping to produce a documentary on the project based on his research and interviews.

He has the support of the Hollywood Heritage Museum in this archeological project and hopes some of the pieces will be curated and stored there, as well as in Santa Barbara institutions.

Two years ago, a $10,000 grant from the Bank of America provided the first scientific analysis of what lay below the sands.

Over the past 10 years and working at it only part time, Brosnan has had to face a series of hurdles in getting an archeological project going at Guadalupe, from land owner conflicts over access to the property to various government agency requirements and regulations.

He thinks he is at a critical point now.

The Nature Conservancy and Santa Barbara County have joined in protecting the land. Trespassers and looters are a certain worry.

There’s been some strong interest at the University of San Diego in turning the dunes into an educational project, a summer school this year for the on-site training of future archeologists. It will take expertise to remove whatever pieces remain, Brosnan says. Hand digging would be required. No bulldozers, no tractors. Brosnan hopes to see $150,000 raised to start the summer dig.

Money was a factor in the DeMille silent film even before it started. Along with a certain gimmick. DeMille and The Times teamed up in a contest to suggest the topic and title of the director’s next film. “$1,000 for an Idea,” the newspaper’s promotion read. “Got one? Watch The Times.” Eight people came up with “The Ten Commandments” and eight $1,000 prizes were paid. The script fell to writer Jeanie Macpherson and the eventual movie featured Richard Dix, Leatrice Joy, Estelle Taylor and Rod La Rocque.

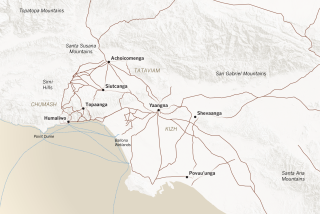

Front-page columns were devoted to stories on the making of the film in 1923, including maps of the site and drawings of biblical scenes.

A Times writer filed this location report:

“The first surprise was the desert itself. The site chosen for the big sets showing the city of Rameses . . . at the very mouth of the Santa Maria Valley. Inland lies the green and fertile fields, but, for a stretch of two miles near the sea beach sands have been blown and drifted into great barren, yellow hills which roll and dip gradually toward the ocean. But this desert, instead of being hot, is swept day and night by cold winds from the sea. There is much fog and little sunshine. . . .

“On the crest of the highest sand hill is the big Egyptian set . . . about two and a half city blocks . . .

“When one desert scene was filmed showing the Children of Israel at their heavy manual labor, clad in little but loin cloths, there was a fifty-mile wind and the thermometer registered down to the forties. The men were covered with goose flesh . . . but they were supposed to be toiling in the hot desert and it was essential that their bodies glisten with perspiration. Five hundred gallons of glycerin were used that day, in lieu of the sweat of toil, but no one grumbled.”

After 10 years, Brosnan remains optimistic about this Hollywood project. He, too, has no grumbles.

Will there be some financial return for the 10 years of research and work and dune trekking? “Not really,” he says. “Maybe when the documentary is finished there might be some profits, but who makes money making documentaries?”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.