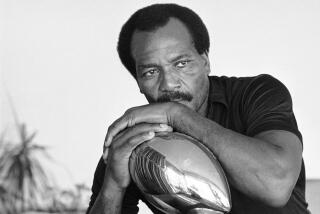

Toughest Test : Football Executive Jim Finks Has Always Tackled Difficult Projects, but Now Battles Lung Cancer

- Share via

NEW ORLEANS — Two days before the NFL draft last April, executives of the New Orleans Saints realized that there was something terribly wrong with their general manager.

During 18-hour discussions about the future of the franchise, Jim Finks twice acted out of character.

First, he ordered everybody to the golf course.

“He said, ‘We’ve had enough, let’s get out of here,’ ” recalled Jim Miller, the team’s vice president of administration. “We thought, Jim Finks is doing this right now? ‘ “

Then, several hours later, Finks was physically unable to finish the 18-hole round.

“That is what makes this so hard to deal with,” Miller said. “Because to us, Jim Finks was never mortal.”

Finks’ legendary armor has been pierced, through perhaps his only weak spot.

Finks, a longtime chain smoker, has lung cancer. By the time it was diagnosed on April 29, it had already spread.

Doctors were forced to remove a lump from his neck and immediately begin chemotherapy treatments, which club officials say have been successful.

But Finks, 65, has been to the office infrequently as he fights a disease that claims 87% of its victims in the first five years.

After watching him lead the failing Minnesota Vikings, Chicago Bears and Saints to unexpected success, the football world is hoping that he can now use that same magic on himself.

“Dad is at his best when he could most easily knuckle under,” said Jim Finks Jr. “We can only hope and pray.”

Pete Rozelle has sent his best wishes. Joe Montana has done the same. The first order of business at the June owners meetings in Atlanta was a full report on Finks’ condition.

“Everybody has been very concerned,” said Don Shula, Miami Dolphin coach.

Many Saints fan are even having Masses said for his recovery.

“From a fan’s standpoint, if we should lose him . . . God forbid,” said Marie Knutson, president of the 2,000-member Saints’ booster club.

Finks, though, remains Finks. A close friend, Paul Buckley, called him at home last month, and Finks said, “Hey Paul, how are you feeling?”

“You jerk,” Buckley replied.

Buckley, general manager of a New Orleans hotel, later laughed about the exchange.

“Only Jim could pull something like that off,” he said. “The man wants to know how I’m feeling? Even now, it’s like he has his finger on everyone else’s pulse.”

Reading those pulses helped the plain-speaking Finks rise from his rural roots in Salem, Ill., to the top of the sports world in 1989.

That year he was the only candidate recommended by a search committee as the new commissioner of the NFL. On July 6, he gathered his wife and four children at an airport hotel in Chicago for the election and subsequent celebration.

But an uprising by the league’s newer owners, who wanted more than one candidate strictly on principal, canceled the party. Finks was defeated by three votes, lawyer Paul Tagliabue carrying the day.

Tom Benson, owner of the Saints, pleaded with him to publicly decry the rebel owners. Finks shook his head.

“Just let it go,” he said.

He quietly boarded a plane the next day and returned to New Orleans.

It was this sort of emotional balance that helped Finks in professional football jobs that have included quarterback, assistant coach, scout and general manager.

“During all of our ups and downs in New Orleans, he has been our one constant,” Miller said.

Finks is no more complicated than his sayings, which co-workers scribble on notepads for posterity.

“That guy could talk a dog off a meat truck.”

When Finks joined the Minnesota Vikings for his first NFL general manager’s job in 1964, they had gone 10-30-2 in their previous three seasons.

Instead of panicking, he spent three years building, then hired Bud Grant.

Three years later the Vikings were in the first of their four Super Bowls with Finks-built teams. Except that Finks was around for only two of those big games.

“Once things reach status quo, my dad feels he has to move on,” Jim Finks Jr. said. “He always has to have those challenges.”

So, in 1974 he took over the Chicago Bears, who had not won a championship in 11 years. In the previous three years, they had gone 13-28-1.

By 1977, they were in the playoffs. Before he left in 1983, he had acquired 19 of the 22 starters for the Bear team that won the Super Bowl in 1985.

“We’re hotter than a deep-holed stove.”

He didn’t join the Saints until 1986. In the interim, he served as president of the Chicago Cubs, who in 1984 happened to win their first championship in 39 years.

On the day they actually clinched the East Division title, he was nowhere to be found. Something about wanting to make sure everybody else got the credit.

“That guy is tougher than a boiled owl.”

Finks was still out of football when Benson, an automobile dealer and banker, bought the New Orleans Saints in the summer of 1985.

“I didn’t have the experience, time or desire to run a football team,” Benson said. “Finks was the one guy in the league who could do it all. He was the guy I had to have.”

Soon after Finks was hired, the face of a losing organization was lifted.

Finks hired Jim Mora as his coach, started a marketing department that included off-season caravans, and reworked everything from budgets to vacation policies.

A year later, the Saints had their first winning season in the franchise’s 21-year history.

They have had winning seasons in five of the last six years and have sold out the 69,056-seat Superdome for 20 consecutive games.

“Jim is a very big reason for everything we’ve done,” said Benson, who loves to sit with Finks during practice. “He can look out on a field and see something in 15 minutes that it takes scouts six months to figure out.”

Benson’s eyes redden when he talks about Finks, and he actually broke down during the formal announcement of Finks’ illness.

With Benson, it’s personal. His son, Bob, died of lung cancer in 1986 at 36.

And Bob, like Finks, was a smoker.

“Jim tried to quit smoking,” Benson said. “He wore those (anti-nicotine) patches, he tried everything. I used to get mad as hell at him about (his smoking). I told him I would not meet in his office because it smelled so much like smoke.”

When Finks visited Benson’s Texas ranch, he was ordered to step outside if he wanted to smoke.

“I know what smoking can do,” Benson said softly.

Other friends tried other ways to persuade Finks to quit. Miller, who spent much time in smoke-filled rooms during meetings, once put a tiny fan on Finks’ desk as a joke.

“I turned it on, it started blowing smoke back at him, and he said, ‘Cut it out. You’re just like Maxine (Finks’ wife),’ ” Miller said. “We respect him so much that we left him alone on the issue.”

Said Benson, “You got to understand, Jim is just one of those old-time guys.”

On the tennis court, despite his smoking, Finks would run opponents until they wanted to quit. And he would never quit first.

“He wanted to play at 6 every morning, but I talked him down to 6:15,” said Philip C. Ciaccio, a New Orleans appeals court judge and one of Finks’ tennis partners. “We would start playing, and he would not stop. Not for a break, not for a drink of water, not for anything. He has that old football mentality.”

A game of squash would turn close friends, Finks and Buckley, into brief enemies.

“We would finish the game and not talk to each other for 15 minutes,” Buckley said.

Finks is the same way when negotiating contracts. No general manager plays harder.

Mike Merkow, while negotiating receiver Eric Martin’s contract in New Orleans before last season, angrily stormed out of breakfast with Finks.

“I couldn’t believe what he was saying about my client,” Merkow said. “I couldn’t take it anymore. I just hope Jim got stuck with the bill.”

Whatever Finks said, it could not have been much worse than the way he described Martin publicly. In a local newspaper, he called him “a descending player.”

“I was furious that he actually said that,” Merkow said. “But at least you knew there was no bull there. He was tough, but at least he was honest.”

Finks is one of the few men who ever gave Jim McMahon reason to wear those sunglasses. During one of their first negotiating sessions after the Bears had drafted McMahon in 1982, Finks brought the cocky young quarterback to the verge of tears.

“By his own admission, the guy is a dinosaur,” Miller said. “One of the things I miss most about not having him at work is that I can’t go into his office after talking to an agent and say, ‘Wait until you hear what he is asking for now!’ ”

Not that Miller doesn’t still talk to Finks. At least once a day, Finks is in touch with his staff as he helps run the team from home.

In fact, three weeks after his illness was diagnosed, he had a staff meeting in his hospital room.

Finks’ work ethic is evident even in his photograph in last year’s media guide. While all other Saints executives and players were photographed against a plain background, Finks is shown sitting at his box at a football game.

He obviously had no time for a photo session.

Some wonder if his hard work contributed to the onset of the illness. The two months before diagnosis were two of the most difficult of his career.

He allowed quarterback Bobby Hebert and running back Craig Heyward to leave the team as free agents. He signed free agent quarterback Wade Wilson. He traded linebacker Pat Swilling. He matched a $10.4-million offer sheet for defensive end Wayne Martin.

Considering that all five players were high-profile veterans, each transaction extracted a bit more from him.

“For him, the mission always came first,” Miller said. “It was like his personal health didn’t matter. He was pale, coughing, congested, and still working.”

In his last tennis match before getting sick, Finks told Ciaccio he was too ill to finish the set. But after a 10 minute break--his first break in three years of matches--Finks insisted on finishing anyway.

On the morning of the second day of the draft, he phoned the office and informed staffers that he was staying home. An hour later, he was pulling into his parking space.

The next day he entered Southern Baptist Hospital, where he remained for most of the next month.

“I think a combination of all the stress had to hurt him,” Mora said. “Jim kept hanging tough and hanging tough until he couldn’t hang tough anymore.”

After the problem was diagnosed two days later, one of the first things Benson did was buy little plastic signs and have them put up on the front doors of every facility owned by the team.

The signs have only two words. But they are words that speak volumes about the feelings of an organization that can’t bear the thought of losing its leader:

“No Smoking.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.