A Money Pitcher With a Wealth of Experiences : Financial Adviser Once Posted ERA of 0.00 at Notre Dame

- Share via

He didn’t know it at the time, but Bob Westland already was making the transition.

Sure, he was a professional ballplayer, but the economics degree he’d earned at UCLA was fast being put to use.

Westland never scaled the minor league ladder into the majors--it’s arguable whether he played in the real minors at all--but he sure knew all about dollars and sense. So what if his fly-by-night, rookie-league team was as broke as a balsa bat.

Players could still dream of the big leagues and bigger bucks, and Westland certainly could explain the economic significance of mucho dinero. Besides, economics is largely theoretical, just like the team’s paychecks.

Even the biggest numb skull on his rag-tag team saw the light when Westland explained how money works.

“Bob, what’s eco-nomics?” the teammate asked.

Westland launched into a meandering discourse on the hierarchy of needs, the intricacies of budgeting and macroeconomics. . . . The player returned a blank stare.

Hmm, Westland thought, I need to explain this in terms he can understand.

“What’s the most important thing in your life, the thing you need most of all?” Westland said, hoping to detail a connection among purchasing power, basic human necessities and expendable income.

“Dip,” the teammate chirped.

“OK, a can of chew costs $2,” Westland said. “Let’s say you have $100 and you need 20 cans. Now, what’s the second most important thing in your life?”

“Girls,” the teammate said.

“OK, let’s say a date costs $50,” Westland said. “How much do you have left, and how much can you spend on each?”

Not much. The teammate, feeling more like a pauper with each passing second, seemed to understand. Not that it really mattered.

“The owner never paid us, anyway,” Westland said.

Westland, an investment counselor in Fort Worth, has always been a bottom-line guy, even in high school.

As a senior at Notre Dame High in 1979, he didn’t allow an earned run in 65 2/3 innings of Del Rey League play, tying a Southern Section record for lowest single-season ERA. Nobody has matched the feat since.

An accounting of his performance in ’79 shows that Westland was practically unbeatable, compiling a 24-1 combined record in high school and American Legion play. His lone blemish was a 1-0 loss to St. John Bosco, when Notre Dame allowed an unearned run in the sixth inning.

Westland, 32, went on to play at UCLA for four years and played pro ball for two seasons in two countries. He never made the majors, but as they’d say in Econ 101, he sure got his money’s worth.

Westland’s simple-minded teammate never asked Bob about his primary human needs. The answer at the time would have been simple: baseball.

*

Westland had not yet been anointed king of the hill. First, he had to build his throne.

On Super Bowl Sunday, in the winter of ‘79, Westland and his best friend, Frank Miceli, dragged out the rakes and shovels and went to work while the rest of the world was watching the Dallas Cowboys and Pittsburgh Steelers.

The pair fastidiously rebuilt the pitcher’s mound at Notre Dame. They had the Army Corps of Engineers come and survey the base lines and foul poles to verify distances and angular accuracy. They mowed the field on weekends. They lined it with chalk before games.

“We wanted everything to be perfect,” Miceli said.

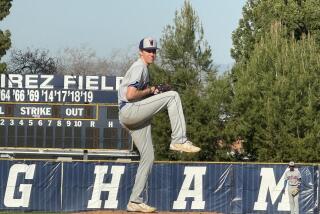

Westland basically was. A 6-foot-2, 200-pound right-hander, Westland was a hulking presence on the Notre Dame mound, which by some curious coincidence was two or three inches higher than the rules allowed. Guess the Corps missed it.

“I had a decent fastball, a pretty good curve and a slurve-slider,” Westland said. “But the biggest thing was, I had a rubber arm. I would have pitched every day if they’d have let me.”

He bounced along all spring and the opposition mounted nary a whimper of protest. He finished 12-1, which included a 176-pitch performance in a 6-5 playoff victory over a Servite team that featured future big leaguers Mike Witt and Steve Buechele.

“We knew he’d be our No. 1, but I don’t think anybody thought he’d have that kind of year,” said his shortstop, Bob Mandeville, who later coached baseball at Notre Dame. “What a year, what an ERA: Oh-point-oh-oh.”

The only oh-no came when Mandeville threw away a late-inning grounder for an error in the loss to St. John Bosco, allowing an unearned run to score.

Miceli remembers. Westland remembers. Mandeville, proving that selective retention is alive and well, does not.

“Tell him that if, in fact, I clanked that one, that I’m sorry,” chuckled Mandeville, now an assistant men’s basketball coach at San Diego State.

The most consistent clang, though, was made as Westland slammed the door on the opposition.

“I might have been lucky once or twice on bad calls by the umpire, or on a ball that barely went foul,” Westland said. “But I was pretty good too.”

He was an All-Southern Section selection and was chosen to play in the Bernie Milligan all-star game at Dodger Stadium.

He didn’t realize it at the time, but perhaps the Milligan outing proved he was human after all. Facing high school all-stars from throughout the San Fernando Valley, he got the starting nod . . . and walked six batters in three innings.

“I was scared to death,” he said.

It would be two more years before he saw significant action again, because Westland’s college career didn’t exactly follow the high school script. He earned a partial scholarship to UCLA, where he was told he didn’t throw hard enough to make the starting rotation. For most of his first two seasons, he pitched for the junior varsity.

“It was a humbling experience after my career year, if you will,” Westland said.

The kid who once volunteered to mow the lawn at Notre Dame was asked to perform janitorial services in a blowout loss to Stanford during his sophomore year. In his first varsity appearance, with UCLA trailing, 16-2, Westland was sent to mop up.

The first batter he faced had already clubbed two homers. Westland wasn’t exactly shy in his NCAA debut. This was a fine how-do-you-do.

“I threw the first pitch right at his head,” Westland said. “Nice introduction.”

Sometimes, he was on the receiving end. When Westland was a senior, Stanford’s Eric Hardgrave gave one of his pitches a huge send-off. Playing at Stanford’s Sunken Diamond, Westland served up a home run ball that was hit an estimated 500 feet. Afterward, Stanford Coach Mark Marquess called it the longest homer he’d ever seen.

Miceli was an eyewitness. He charitably called it “titanic.”

The blast landed, eventually, on the school’s rugby field beyond the fence in left-center field.

“Hey, for a ball to go that far, it had to be thrown pretty hard, right?” he quipped.

Westland supplied more than just comic relief, however. As a senior in 1983, Westland led UCLA pitchers in appearances (32) and saves (four). He was 5-2 with an ERA of 3.70 and was a combined 10-2 in his last two seasons.

When draft day rolled around in June of ‘83, the phone call he was expecting never came. Six of his UCLA teammates were picked--including infielder Rich Amaral and pitcher Pat Clements--but Westland was passed by.

“It was the darkest day of my life,” Westland said. “I didn’t care if I was taken in the 40th round, I wanted to play pro ball.”

And so he did, sort of. In the legal profession, they’d call it pro bono , which means working for free.

Westland was asked to play in a new, privately financed rookie league, and he was too gung-ho, too restless and too gullible to decline. He reported to a team in Tooele, Utah, where he was expecting to draw $500 a month in salary.

In his current occupation, Westland would call the league a high-risk, low-yield proposition. As it turned out, 30 or 40 games into the season, players were forced to walk out because their paychecks bounced like a 50-foot curve. The league went el foldo, and Westland went south in 1984. An acquaintance from UCLA hooked him up with the Northern Sonoran League in the scorching Mexican desert. Talk about the cactus league.

It was every bit as glamorous as it sounds, but it technically was pro ball, and that was enough for Westland.

“It was a scream,” Westland said.

He reported to the Tijuana Yankees, an oxymoron if ever there was one. The team owner, it seems, had a thing for the real Bronx Bombers. In fact, he outfitted the team in copycat pinstripes, the whole works.

Any similarity to Steinbrenner’s boys ended there.

*

Hasta la vista, baby.

Westland shook the sleep from his eyes. Another overnight bus trip down another washboard highway.

It was early, the crack of dawn. A few teammates were curled up in the luggage compartments overhead. He peeked down the aisle. This time of day, the Sonoran League was the snorin’ league. Everyone was snoozing.

Everyone.

“I look up at the driver, and the guy’s nodding off,” Westland said. “It scared me to death. I ran down and started talking to the guy and giving him coffee to keep him awake.”

The Sonoran league was always an eye-opener for Westland. Right from day one. In Tijuana’s home opener, Westland was tabbed the starting pitcher. About 4,000 fans showed, including Miss Tijuana, who was there for the gala opening-day festivities.

“She was really cute,” Westland said. “I kept thinking, ‘How can I meet her?’ To hell with the game.”

Not a bad philosophy in Mexico, where it’s usually a good idea not to sweat the small stuff. Heck, none of the locals did, so why should Westland?

On another trip, the team bus pulled into a gas station. A Mexican ambulance, en route to the emergency room of a nearby hospital, pulled up at another pump to refuel.

Suddenly, the guy in the back of the wagon went into cardiac arrest. Alas, nothing could be done, and the patient died.

The ambulance attendants were obviously distraught, Westland said. Overwhelmed with grief, consumed by guilt.

After filling up their gas tank, the attendants proceeded to spend the next few minutes sucking down Coronas and shooting the breeze with the ballplayers.

“There were some wild times,” Westland said with a chuckle. “I mean, the guy had just died. I saw some crazy things.”

The weather was hot, but the living arrangements weren’t. Westland and several of his teammates stayed in the team hotel for much of the season. The Ritz, it wasn’t.

A few years ago, Westland and Miceli went back to the former’s Tijuana stomping grounds.

Miceli was mortified.

“You wouldn’t go there without a gun,” he said. “Playing in Mexico is something you’d only do when you’re young, like getting drunk and throwing up out the car window.”

Miceli, a restaurateur in Los Angeles, said that Westland spotted a few familiar faces during their tour.

“Remember me?” Westland said.

Eyebrows moved up foreheads. The locals eyed the beefy gringo, then responded. The verdict?

“Who knows if they remembered?” Miceli said. “They were speaking Spanish. They might have been saying, ‘We hated you then, we hate you now.’ ”

Like most looks into the rear-view mirror, time has tempered the few bad memories of Westland’s expedition. What seemed terrifying at the moment is positively amusing in retrospect.

Passing the time could be brutally tough--and dangerous. During the 1984 NBA Finals, Westland and some teammates searched high and low for a bar with a television. It seemed that everybody in town with a TV was watching soccer.

Finally, they cut a deal with a bartender: Let us watch the Lakers and Celtics and we’ll buy so much beer that you can retire early.

After three quarters, the bartender switched the channel to soccer, then thumbed his nose at the ballplayers.

“We almost had a riot,” said Westland, whose blood-alcohol level by then was considerably higher than his high school ERA.

Finally, a group of Mexicans at a nearby table invited the players to another bar to watch the game. Follow us, they said.

“It turned out that one of the guys in their group was the biggest drug dealer in Mexico and the other was some kind of high-ranking federal official,” Westland said.

Fast company, indeed. But the players were celebrities too. Westland, one of four Americans on the Tijuana roster, was a relative king. He was paid a princely $800 a month, tax-free.

Let’s see, how did that speech on economics go? What are my main human needs, how much money do I have to spend. . . .

“Tequila was only about 40 cents a shot,” he said. “And the Coronas were always cold.”

He was popular among the locals and picked up the nickname, “Professor,” because he helped some of his teammates learn the rudiments of English. He, of course, learned all the Mexican cusswords--not to mention the basics of Baja baseball--and adjusted his expectations accordingly.

None of the fields in the league had grass, for instance. Not in the infield, not in the outfield.

“But it was some of the nicest dirt you’ll ever see,” Westland said.

In Mexico, his pro career finally died and was buried. After one year in Yankee pinstripes, Westland recognized his future as a ballplayer was as limited as his Spanish.

He took a job at a bank and did what most former ballplayers do: played softball, got married and started a family. He now specializes in selling investment portfolios and mutual funds.

. . . . what are the most important things in your life, the things you value most of all?

Westland’s priorities, obviously, have changed. His dream, well, that’s another thing altogether.

“I miss the game like you can’t believe,” he said. “But it was fun while it lasted.”

Southern Section Top Season ERAs

Top single-season earned-run averages in Southern Section baseball history:

ERA Pitcher, School Yr 0.00 Bob Westland, Notre Dame ’79 0.00 Bob Coleman, S.Pasadena ’59 0.08 Bob Goodyear, L.A. Lutheran ’73 0.11 Denny Lemaster, Oxnard ’58 0.12 Randy Banuelos, Channel I. ’70 0.13 Jay Dahl, Colton ’63 0.15 Jerry Meyer, L.A. Lutheran ’67 0.16 Rick Stewart, Fillmore ’76 0.18 John Herbst, Notre Dame ’63 0.20 Jim Peterson, Sonora ’73

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.