Motorcyclist Is Gone, but His Long Love Affair With Bikes Will Continue

- Share via

LONG BEACH AREA — People who knew the late “Wild Bill” Cottom--and who understand the mystique of high-performance bikes--aren’t at all surprised that Cottom’s cremated remains are resting inside a motorcycle gas tank bolted to the wall of a San Pedro motorcycle shop.

They know that Cottom, a legendary motorcyclist who died last month at age 86, wouldn’t have been happy anywhere else.

“Yep, he’s still right here with us,” said Jim Rutherford, 27, Cottom’s grandson, nodding toward the shiny black Vincent motorcycle fuel tank on a wall at Cottom’s shop, Century Motorcycles. “He wouldn’t have wanted it any other way.”

Those outside the motorcycle world may not be familiar with Cottom’s name. But among motorcycle enthusiasts his fame was such that last Sunday more than 1,500 bikers of every description showed up at his shop on Pacific Avenue to pay homage to his memory.

“He was a total legend,” said LeniCazdem, 45, of West Los Angeles, who with her daughter Lauri, 29, rode to the event on their Harley-Davidsons.

As for Cottom being entombed in the gas tank of a motorcycle, well, Cazdem understands.

“For bikers, there’s always a lot of ritual attached to it,” Cazdem said. “Like they’ll mount a guy’s motorcycle on top of his coffin and lower it into the ground with him. It’s not at all unusual.”

“For a lot of people motorcycles aren’t just a hobby,” said Kevin Johnson, 33, manager of the Garage Co., a combination book store and motorcycle shop in Culver City, who attended the party for Wild Bill. “Motorcycling becomes an all-consuming passion, it becomes a major facet of their life--and death.”

*

Motorcycles were Cottom’s passion ever since 1919, when he was a 12-year-old living on a Kansas farm. A cousin let him ride his Reading Standard motorcycle, and from then, friends and family members say, Cottom was hooked.

Later, with money earned working at a general store and as an underage professional boxer--he won the Kansas light-heavyweight boxing championship at age 17--Cottom bought a brand new Harley-Davidson, the first of many motorcycles he would own.

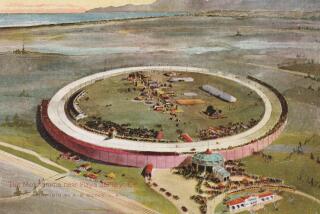

During the early years of the Depression, Cottom worked as a sparring partner in Chicago and raced motorcycles for cash on wooden board race tracks--one of the most dangerous kinds of racing there was. Cottom came to San Pedro in 1935 to help his brothers run their Century Sign business.

Cottom’s son Billy Gene, who was later killed in the Korean War, rode motorcycles with his father and introduced him to Vincent motorcycles, the British-made line that many people call the “Rolls Royce of motorcycles.” Cottom went on to own more than 400 of them.

Cottom and his favorite motorcycle, an early 1950s Vincent Lightning, became famous in racing.

“He’d run his Vincent Lightning up on the (Palos Verdes) peninsula,” grandson Rutherford said, “and people would come from miles around to race him. They’d race for pink slips, and he got a lot of bikes that way. He was a good rider; he never got hurt on a motorcycle.”

In 1965, Cottom, who had been trading and selling motorcycles out of the back of his sign and hardware store for years, decided to get into the motorcycle business full time.

He opened Century Motorcycles at Pacific and 17th Street that year, specializing in vintage and British-made motorcycles such as Vincents, BSAs and Triumphs. The shop soon became a prominent hangout for bikers from throughout the Los Angeles area and beyond.

“He considered everybody his friend,” Rutherford said. “There was never any pressure to buy anything. He was just as happy to talk to you as to sell you something.”

Cottom gave up riding motorcycles after suffering a stroke at age 70, but he continued to work in the motorcycle shop every day.

Meanwhile, his daughter, Cindy Rutherford, who like her son Jim works at the shop, started throwing annual Father’s Day and Christmas parties for him at Century Motorcycles.

Last Sunday’s was the biggest ever.

“He never wanted anybody to mourn over him,” Jim Rutherford said. “He wanted everybody to have a good time, and they did. We’re going to keep on having the parties, twice a year. We always will.”