They Conned America : In 1956, Herbert Stempel took a dive on the TV quiz show ‘Twenty-One.’ : Why did he do it? Why did America take it so hard? ‘Quiz Show’ tells the story of how a simple TV show robbed a nation of its innocence.

- Share via

Anyone alive in the late 1950s remembers the national love affair with the television set, and the deflowering of America by the most seductive of all its offerings: the popular quiz-show programs and their rags-to-riches promises.

On Wednesday nights in late 1956, restaurant business slowed to a halt, movie theaters were empty and commerce in general stopped across the country as friends and family gathered around flickering black-and-white television sets to cheer their favorite NBC “Twenty-One” contestants. Quiz-show mania hit approximately 50 million Americans who tuned in to watch people much like themselves become rich beyond their wildest dreams--simply by knowing the right answers.

The concept was brilliant. What could be more American--more democratic--than earning riches based purely on intelligence?

But the need for riveting programming ultimately displaced the very thing that made the quiz shows so enticing. By the late ‘50s, a scandal involving a scam of huge proportions forced the collapse of the popular shows and left the country disillusioned.

Next month, Robert Redford unveils his newest directorial effort, Disney’s “Quiz Show,” based on the “Twenty-One” scandal that hit just after he moved to New York City as a young acting student.

“The quiz shows were very much a part of the innocence of the country at that time,” says Redford, who co-produced and directed the film. “This was the first shock wave to hit the American public that everything they saw on TV was not the way it was. It was the beginning of the erosion of trust in an institution that was supposed to give us the truth.”

“Quiz Show,” which stars Rob Morrow (“Northern Exposure”), John Turturro (“Barton Fink”) and Ralph Fiennes (“Schindler’s List”) as Charles Van Doren, the academic at the epicenter of the scandal, is an intimate, emotional look at the people involved in the scam and the motivation--mostly greed and power lust--that drove them.

During the 1940s, America was rapt with a radio quiz show called “The 64-Dollar Question.” When television, so much splashier than radio, came along, nothing less than 64 thousand dollars would do.

“The $64,000 Question,” conceived by Lou Cowan, an early TV mogul, became an instant hit when it went on CBS in 1955. The show, whose motto was “Where knowledge is king, and the reward king-sized,” climbed to the No. 1 spot in the ratings in only five weeks. Contestants had the chance to win as much as $8,000 in half an hour, then return the next week to see if they could win more. Viewers identified with the returning players, which built suspense and created celebrities, including a young psychologist named Joyce Brothers, who was the second person ever to win $64,000 when she answered questions about boxing.

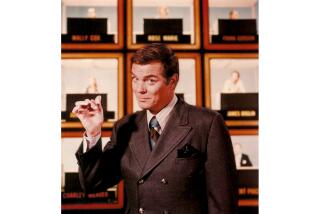

After the blazing success of Cowan’s quiz show, similar programs glutted the networks. “Twenty-One,” which debuted on NBC in September, 1956, was one of the most popular. The show’s premise, based loosely on the card game of the same name, was that two contestants--locked in soundproof isolation booths by an attractive set of twins in evening attire--would answer questions for points. The first to reach 21, without going over, won.

Neither contestant knew how many points the other had, and the difficulty of the questions increased with the number of points he or she bet. When the questions were worth nine or 10 points (the highest bet on a point was 11), they would often have three- and four-part answers. For example, after listening to an aria, the contestant would be asked to name the opera, the aria, the character and the soprano who was singing.

Dan Enright, who created “Twenty-One” with partner, fellow producer and emcee Jack Barry, thought it was destined to be an immediate hit, but he was wrong. Enright later admitted that the show’s premiere was “a dismal failure, just plain dull.” Matthew Rosenhouse, president of the company that manufactured Geritol, the sponsor of the program, sent word to Enright: “Do whatever you have to do, and you know what I’m talking about.”

What the show seemed to lack was drama. It needed players who would come back week after week to battle wits--and to connect with the viewers. The catch was that no contestant, no matter how smart, would know all the answers all the time.

That’s where the problems--and the loss of America’s trust in the media--began.

W hy did “Twenty-One’s” contestants agree to lie to the viewing public? Money, for one thing. Not only did the contestants come away in a few weeks with more cash than they might have made in a lifetime--many tens of thousands of dollars--but they also became overnight celebrities. Besides, the producers were quite persuasive. It’s television , they said. Entertainment .

Yet what made the quiz shows so believable was the effort by the producers themselves to build the image of integrity. On “The $64,000 Question,” the questions remained in a sealed bank vault until guards delivered them in an armored truck directly to the studio on the night of the show. On “Twenty-One,” every detail--from a contestant’s mopping his brow to his asking for a question to be repeated--was choreographed.

One of the most popular contestants on “Twenty-One,” Herbert Stempel (played by Turturro, who gained 25 pounds for the role), was a stocky Jewish man with bad teeth. The folks at home liked seeing the Queens-born underdog shine. Enright and co-producer Al Freedman hyped his background, instructing him to wear the same dingy suit every week and to call quizmaster Barry “Mr. Barry,” instead of Jack, as the other contestants did. They also fed him the questions every week, and coached him on how to create suspense by acting like he was fishing for the answers.

When, after reviewing the ratings after several weeks, the sponsor decided Stempel’s charms had “plateaued,” Enright anointed another king of the show, the dashing Columbia professor Charles Van Doren, and directed Stempel to bow out on a question so easy it would haunt him for the rest of his life. On Dec. 5, 1956, after winning nearly $50,000 (more than any contestant before him), Stempel flubbed the question, “Which movie won the Academy Award for best picture in 1955?” As it happened, he had seen the winning movie, “Marty,” three times. The embarrassment of having to answer “On the Waterfront” would ultimately lead him, in 1958, to report the rigging to authorities. (Stempel, however, was not the first ex-contestant to turn whistle-blower on game shows; a contestant on the short-lived “Dotto” raised the issue earlier in 1958.)

The memory still rankles for Stempel, who is now 67, still living in Queens, with his second wife, Ethel, 66, a computer systems operator. “After 37 years, I’m getting a taste of deja vu,” Stempel, says. “On the set, John Turturro answered to my name. It’s weird to see yourself actually being portrayed in a movie.”

After Stempel’s fall, Van Doren came into his own. Van Doren came from one of the oldest academic families in the country; his father was the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and professor Mark Van Doren, and his uncle was Carl Van Doren, who had won a Pulitzer for biography in 1939. His mother, Dorothy Van Doren, had been an editor of the Nation and a novelist. Charles, not yet a full professor, earned a yearly sum of only $4,000. Although he initially declined to be part of the rigged show, he was swayed by the convincing arguments of co-producer Al Freedman, who persuaded him that his participation would “help glamorize intellectualism.”

And sure enough, the thoughtful, modest Van Doren was an instant hit with the viewers, who wrote him letters telling him that he represented America’s hope for the future of education. Geritol loved him. He kept his title on “Twenty-One” for a record 15 weeks, winning a hefty $129,000--approximately $800,000 in today’s dollars.

“Once I saw him,” says Stempel, “I knew my days on the show were numbered. He was tall, thin and WASPy, and I was this Bronx Jewish kid. It was as simple as that.”

When the time finally came for Van Doren to take his fall, he received a $50,000 per year contract to discuss cultural issues on NBC’s “Today” show with its host, monkey-toting Dave Garroway (played in the movie by director Barry Levinson, whose Baltimore Pictures initially developed the script).

In 1958, Richard Goodwin, a rookie lawyer for the House Subcommittee on Legislative Oversight, read a minuscule story in the newspaper about a nine-month New York grand-jury investigation of the quiz shows. Stempel, still reeling from his embarrassment over “Marty,” had reported the rigging to the authorities. But the findings of the grand jury were sealed to the public. Goodwin, on a hunch, reopened the case. Using Stempel’s testimony and other pieces of incriminating evidence, he pieced together the truth: that “Twenty-One” and several other quiz shows were fixed and that producers and network officials as well as product sponsors helped mastermind the plan. His findings led to the downfall of “Twenty-One,” and, later, full-scale hearings in the House in 1959 and federal regulations of the quiz shows.

America was stunned. When Van Doren, troubled by a guilty conscience and Goodwin’s relentless investigation, finally admitted at the House hearings that he had been in on the scam, it seemed that nothing was sacred. Van Doren’s career and image were shattered. His face, which had appeared on the covers of Time only weeks before as an American icon, now stood for corruption and greed.

An angry John Steinbeck wrote a letter to Adlai Stevenson, which was reprinted in the New Republic under the headline “Have We Gone Soft?” It read: “If I wanted to destroy a nation, I would give it too much and I would have it on its knees, miserable, greedy, and sick. . . . On all levels, American society is rigged. . . . I am troubled by the cynical immorality of my country. It cannot survive on this basis.”

John Crosby, one of the country’s foremost television critics at the time, wrote: “The moral squalor of the quiz show mess reaches through the whole industry. Nothing is what it seems in television . . . the feeling of high purpose, of manifest destiny that lit the industry when it was young . . . is long gone.”

Van Doren was fired from Columbia and retreated to Chicago with what was left of the money he had won, where he made a private life for himself and Geraldine Bernstein Van Doren, whom he had met when she was employed by “Twenty-One” to answer his fan mail. Through a family connection, he landed a job editing the Encyclopedia Brittanica and has never spoken or written publicly of the incident again.

Though Van Doren, now 68 and living in Cornwall, Conn., declined Redford’s offer to participate in “Quiz Show,” Fiennes wanted to meet him at least once to study his mannerisms. The actor, still relatively unknown last year before the release of “Schindler’s List,” drove to Van Doren’s house, waited for him to emerge and asked for directions, claiming he was lost. That anonymous five-minute conversation, Fiennes says, along with many kinescopes of “Twenty-One” and television interviews, gave him what he needed to play the part.

While no one went to jail, Van Doren, Freedman and near ly two dozen contestants were charged with second-degree perjury. Almost all the other quiz show producers lost their jobs and were unofficially blacklisted by the networks for years. Congress passed laws making TV fraud illegal, which have come to be known unofficially as Stempel laws.

But the controversy cost Stempel his public dignity and, he believes, readmittance to New York University to complete his doctorate. (NYU officials say his files state that he was denied readmittance in 1960, but do not provide reasons.) Stempel went into the hosiery business and taught public school before landing in the early ‘80s at the New York City Department of Transportation in Manhattan as a researcher, where he still works. Disney paid him $30,000 to be a consultant for “Quiz Show,” and he currently is at work on a book of memoirs about his experience, only recently having broken his self-imposed silence about the ordeal.

“I was so depressed and so disgusted, I just didn’t want to have anything to do with anything connected with it,” Stempel says. “Finally, I got tired of being in the shadows and said to Ethel, ‘The next person who calls gets my story.’ ”

That person turned out to be Julian Krainin, an Academy Award-winning documentary film maker who was making a film of the subject, “The Quiz Show Scandals,” that aired on PBS in 1991. He went on to become one of “Quiz Show’s” producers.

“What fascinated me about about the subject was that all of us could have been lead down this trail,” says Krainin, now 53. “It was like a Faustian deal with the devil that happened in small, gradual steps and compromises until people became trapped by fame and money.

“Also, you were dealing with one of the most brilliant and clever producers in history of television,” Krainin says about Enright, who died in 1992 at age 74. “Enright was brilliant at not only devising the concept of the game shows, but keeping people in line. He knew how to say the right things and get you to trust him.

“There’s a sadness in Herb and it comes from spending 30 years of his life in shame,” adds Krainin. “When I came to him to do the documentary, I spent a long time convincing him that he had nothing to be ashamed of, but should feel proud that he tried to expose the truth.”

‘I remember watching Van Doren on TV--he was as popular as Elvis,” says Redford, who in 1959 at age 21 won a $75 fishing rod (as an actor that contestants guessed about) on “Play Your Hunch,” a quiz show hosted by Merv Griffin. “Watching him and the other contestants was irresistible. The actor in me looked at the show and felt I was watching other actors. It was too much to believe, but at the same time, I never doubted the show. I hadn’t had evidence television could trick us. But the merchant mentality was already taking hold, and as we know now, there’s little morality there.”

In fact, it was just that commercial mentality that originally made “Quiz Show” a tough sell. Though the newsreel version had all the elements of high drama, no one had been able to make the movie. In fact, TriStar had put “Quiz Show” in turnaround in September, 1992, after developing it with Levinson. Luckily, Disney, which had a Herb Stempel story already in the works, scuttled that project last spring when it persuaded Redford, flush with the success of “A River Runs Through It,” to bring over his version of the tale, which focused the story evenly on the three main players.

“It’s always risky to do a movie from more than one point of view,” says Redford. “Studios tend to like black hats and white hats.” Especially when the movie doesn’t have all the elements of a box-office blowout. But Redford says he isn’t concerned about the lack of high-speed chase scenes and blinding explosions. He says his movie’s theme--ethics--will touch everyone.

“Three decades of scandal after the quiz shows, the country has become numb,” the director says. “There’s a moral ambiguity that has made us change our behavior, hopes and dreams.”

Like Redford, Goodwin, who later became a Kennedy speech writer (and co-producer of the movie), believes that the rigging of “Twenty-One” and the other quiz shows was a symbolic event in American history--one that has had lasting implications. “Certainly up ‘til then people tended to believe their Presidents and believe what they saw on television. Remember, we were only four years away from the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. At that point the country in general was taking a wrong turn in the road.”

That initial loss of faith in the media laid the groundwork for the contemporary understanding that on television, what you see isn’t necessarily what you get; witness TV dramatizations, computer-driven image manipulation and even the “Dateline NBC” investigation, in which the producers rigged an explosion to illustrate General Motors’ dangerously installed gas tanks.

In fact, in this cynical age, it can be a little hard to understand the impact of “Twenty-One’s” blow. To explain the scope of the shock to screenwriter Paul Attanasio, 34, Goodwin suggested he imagine the feeling of betrayal if he were to find out the Super Bowl were fixed. “There was something very noble in Charles’ capacity to feel ashamed,” says Attanasio, who also wrote the screenplay for the upcoming “Disclosure” and helped with rewrites on “Crisis in the Hot Zone,” pre-production on which was shut down recently after Redford abandoned the project. “Just as there was something wonderful about the capacity of the viewers to be outraged. I think that’s all gone.”

Morrow, 31, wasn’t even born during the quiz-show era, but says the movie’s subject matter has a modern message. “Take those so-called reality-based shows,” says Morrow. “People take it, myself included, as fact--reality--but once you put a camera on something, it’s subjective, not objective. I think ‘Quiz Show’ will remind people you can’t take that as the final word, no matter how objective it seems.”

But could a wary public resist another charismatic Van Doren? After all, Americans raise actors and sports figures to godlike proportions all the time. And, like Van Doren, these heroes can let their fans down. “We so want to believe they’re innocent,” says Morrow. “It’s actually good if the guys we deify fall--if you learn the lessons. Unfortunately, instead of learning,” he pauses, “we just make new gods.”*

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.