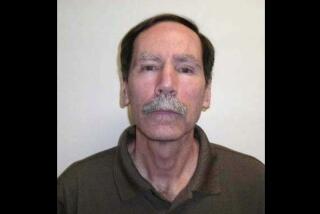

Pillowcase Rapist Out of Prison : Crime: Reginald Muldrew, imprisoned in 1979 after series of attacks in L.A. area, flies to Las Vegas. He tells police there he is ‘passing through.’

- Share via

The so-called pillowcase rapist, who police say may be linked to more than 200 rapes in the Los Angeles area, has left California, authorities said Monday.

Reginald Donald Muldrew, 47, flew to Las Vegas shortly after his release from an undisclosed prison Monday afternoon, said Lt. Brad Simpson of the Las Vegas Police Department.

In an interview at the Las Vegas Airport, Muldrew said he planned to stay in the city only one night. Asked if he had been rehabilitated, Muldrew said: “That is information that will come out if they watch eventually, you know. So right now that’s still up in the air.”

Muldrew was imprisoned in 1979 on four counts of rape, two counts of forced oral copulation with a child and one count of assault with intent to commit rape. He became known as the pillowcase rapist because he placed pillowcases, scarves and blouses over the heads of his victims during the crimes.

He served the last portion of his prison term at Vacaville State Prison, where a Pasadena women’s rights group had planned to hold a vigil to protest his release. But their plans were thwarted when corrections officials Sunday moved Muldrew to an undisclosed location, just as the three members of the Women’s Coalition arrived at Vacaville, said Susan Carpenter McMillan, president of the coalition.

Authorities transferred Muldrew “not just to protect him, but to protect our officers,” said Tip Kindel, a spokesman for the California Department of Corrections. “We had to ensure that we got him from the prison to public property safely. Clearly in a bad situation, our officers could get hurt trying to protect him.”

But McMillan said she had planned a peaceful demonstration and called Muldrew’s removal “outrageous.”

“We had three women and eight cameras,” she said. “I told them they could detain me until he was far enough away. Why would they make parking arrangements for me, if they knew he wasn’t going to be there?”

Even after Muldrew’s plane landed in Las Vegas, authorities would not reveal from which prison he was released because “we may want to use this procedure again,” Kindel said.

McMillan said she was considering traveling to Las Vegas today to warn women about Muldrew’s release and “spread his picture around.”

But the word apparently was already out. A full squadron of Las Vegas police officers met Muldrew at the airport to “make sure he is clearly aware of our sex offender registration law, and tell him that if he did not register within 48 hours, he would be arrested,” Simpson said.

According to Nevada state law, previous sex offenders have to register with local police departments whenever they move to or within the state. California has a similar but more stringent law: If a sex offender fails to register in California, he can be charged with a felony and face up to three years in prison. In Nevada, the violation is a misdemeanor, and the offender can spend a maximum of six months behind bars.

Simpson said he believes that Nevada’s more lenient laws are only part of Muldrew’s decision to go there, but the Police Department’s swift attention may hasten his departure.

Met by at least six officers at the airport, Muldrew told police, “I’m just passing through town.”

Muldrew spent his own money on the plane ticket to Las Vegas, authorities said.

When he came up for parole last December, 3,000 residents of Covina, where Muldrew was scheduled to be released, rallied in protest. Their complaints prompted Gov. Pete Wilson to publicly sign a bill into law that keeps sexual offenders in psychological custody for at least two years after their prison term, until they can pass a psychological exam. Muldrew, who failed a similar examination, was not subject to the law, which does not take effect until Jan. 1.

Muldrew served his parole in prison because psychiatrists determined that he suffered from a mental disorder for which there is “no cure in society,” said Christine May, a state Department of Corrections spokeswoman.

While on parole, he refused psychological treatment, an option he had under the current law.

“Sex offenders who want to change can learn to recognize the triggers and remove [themselves], but he refused treatment,” May said.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.