‘Incarceration Coverage’ Helps to Put Downey in the Picture

- Share via

Film companies typically pay insurance companies for policies that protect them from such possibilities as on-set accidents or weather calamities, but a major Warner Bros. movie has come up with what may be an industry first: incarceration coverage.

The studio recently paid a premium in the “low-to-mid six figures” to cover for the possibility of such an eventuality in the case of Robert Downey Jr. in the big-budget film “U.S. Marshals,” also starring Tommy Lee Jones and Wesley Snipes.

Because of several well-publicized scrapes with the law in connection with heroin and cocaine possession, Downey had been considered virtually uninsurable.

Downey’s recent troubles began on June 23, 1996, when he was arrested. He subsequently agreed to enter a non-locked drug treatment facility. Less than a month later, he was arrested on suspicion of drug possession and trespassing in a Malibu home and was ordered to receive treatment.

He was ultimately sent to jail in late July after his third arrest for having left a drug treatment program without permission and was ordered by a Superior Court judge to complete six-month rehabilitation treatment at a locked facility.

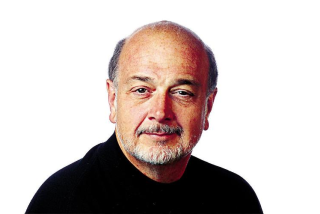

In the 11 months since that court order, the actor, 32, has completed drug rehabilitation and worked on two independent films. This week he began working in “Marshals,” a spin-off of “The Fugitive” shooting in Chicago and scheduled to open early next year.

It is Downey’s first big studio film since his arrests, and his participation was made possible by a specific policy covering “lock-down and incarceration,” sources said.

“He has to be insurable to work,” said a source involved in the coverage. “There was an atmosphere in which this artist couldn’t work.”

Enter Donna Smith, head of a company called Entertainment Coalition, a management company that coordinates completion bond and insurance services for the entertainment industry. She, along with Chicago-based CNA and a broker from Reuben Co., engineered Downey’s unusual policy.

Smith believes that studio executives offered Downey a lead role in the big-budget film partly because of his having successfully completed other pictures without incident and also because of a loosening of court restrictions governing Downey’s punishment.

One of the terms of Downey’s rehabilitation originally called for him to work as much as possible, but until recently the court order had made that exceedingly difficult, according to sources close to the actor. The order required Downey’s immediate incarceration should he be found under the influence of drugs. Such an action could seriously jeopardize a production by slowing down shooting or stopping it altogether, resulting in a loss of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Downey will have to undergo twice-weekly random drug tests while filming “Marshals,” sources close to the actor said.

“I think he’s bottomed out and he’s a bright boy and knows he’s got to behave himself,” a source close to the insurance negotiations said.

Downey has received many film offers since his arrests last summer, said ICM agent Nick Styne, who represents Downey with Ed Limato.

In one of the offers, from Mandalay Entertainment, producers asked Downey to pay a reported $700,000 out of his own pocket to cover insurance costs. Downey refused.

Another offer--”The Gingerbread Man,” directed by Robert Altman from a John Grisham script--did materialize, but producers went out on a limb in casting Downey.

Production insurance is typically required on every film. But “Gingerbread Man” producer Mark Burg took the unusual and risky step of not securing a policy on Downey. The premium would have cost the production $1 million on a film with a budget of less than $30 million.

“I could not afford to hire Robert Downey Jr. if I had to pay that exorbitant premium, so I basically just gambled, took a shot,” said Burg. “I felt that Robert really wanted to do the movie badly and I felt he’d been crucified enough and wanted to go back to work. I knew where he was at all times, and I made sure I could find him . . . . You’re talking about a couple hundred-thousand dollars a day if an actor disappears. . . . He turned out to be one of the most professional actors I’ve worked with.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.