Publishers Vie for Bigger Pieces of Pie

- Share via

The big story in publishing this year was bigness itself.

Large companies became much larger, heralding major changes in the book business during the years ahead.

Bertelsmann A.G., the German media giant that already owned the Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, became the world’s largest English-language book publisher in July by buying Random House and its various imprints from the Newhouse family for an estimated $1.4 billion. The enlarged entity took the name Random House Inc.

Bertelsmann then dropped plans to start its own global online bookstore, instead agreeing in October to pay $200 million for a 50% stake in Barnes & Noble’s online site and another $100 million to advance the venture.

What would it mean to authors and literary agents--and readers, too--now that Bertelsmann would control Random House, Alfred A. Knopf, Doubleday and so many other affiliated outlets of literary expression? What would it mean to Bertelsmann’s book-publishing competitors that the conglomerate now had a business partnership with Barnes & Noble, the industry’s largest retailer?

These questions were tough enough to answer before everyone had to process still another major development. In November, Barnes & Noble further stunned the industry when it announced plans to pay $600 million for Ingram Book Group, a leading wholesaler that independent stores call on to replenish stock and that Amazon.com has used to fill more than half of the orders it receives over the Internet. In the wake of Bertelsmann’s investment in Barnesandnoble.com, B&N;’s purchase of Ingram’s distribution centers around the country made it strikingly clear that the giant bookstore chain wants to compete much more aggressively with Amazon for sales that are only a mouse click away.

Forecast: Bruising online competition ahead.

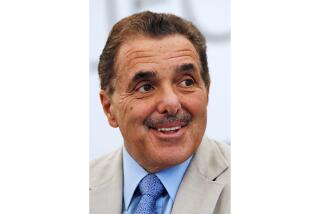

“The year was like a shock sandwich,” said Jack Romanos, the president and chief executive officer of Simon & Schuster, which is the publishing arm of Viacom Inc. “There was the shock of the Bertelsmann-Random House merger and then the shock of the B&N-Ingram; deal. Though they are on two totally different planes, each promises to impact on the publishing, distribution and retailing sides of the business.”

In an interview last week, Romanos added that the big deals of 1998 have “redefined size.” Certainly, as Bertelsmann and Barnes & Noble grew much larger in 1998, Simon & Schuster, whose divisions include Pocket Books and Scribner, diminished in size. This resulted from another big transaction, completed in November-- Viacom sold off S&S;’ educational, reference and professional operations to Pearson PLC, the British media colossus that owns Penguin Putnam Inc., for $4.6 billion.

“On the publishing side, we’re all wrestling with the impact that size will mean on the mega-publishing level,” Romanos went on. “There are cost incentives that should benefit the P&L; [profit and loss]. But how anyone can manage that much publishing under one roof remains to be seen. It’s premature to say if it will be good or bad. It will probably be both.”

Literary agent Jean V. Naggar, who is president of the Assn. of Authors’ Representatives, said the dramatic consolidation in the publishing industry this year concerns writers and their agents. “I’m not sure how it’s all going to play out,” she added.

Among the concerns for writers is whether the consolidation of top publishers into fewer hands will lessen the competition for manuscripts and thereby limit the size of advances paid to authors.

In addition, Barnes & Noble’s pending purchase of Ingram is being vigorously opposed by the American Booksellers Assn., which represents independent stores. “If the deal is completed, independent bookstores will have to rely on their largest competitor for their books,” the ABA says in a statement that it urges members to display. “It’s as if Burger King and Wendy’s had to buy their French fries from McDonald’s.”

Some authors also have expressed worries to the Federal Trade Commission, which has yet to approve the Ingram purchase. The writers say they fear it will create a greater appetite for big bestsellers, at the expense of titles that might be expected to sell only a few thousand copies each, and at the expense of independent bookstores that have helped keep these so-called midlist books in circulation.

Barnes & Noble Chairman Leonard Riggio said that the Ingram acquisition will give B&N; “many benefits and synergies,” including the faster delivery of books. John Ingram, who is chairman of Ingram and will become co-vice chairman of B&N;, has sought to assure independent customers that Ingram will continue to offer them the same terms available to the chain.

On the opposing front, Amazon CEO Jeffrey Bezos responded to the B&N-Ingram; announcement with a line that was quoted widely in the media: “Goliath is always in range of a good slingshot.”

Meanwhile, addressing questions raised by Bertelsmann’s expansion this year, company executives have repeated assertions that they wish to preserve the autonomy of their various divisions and the diversity of titles that they publish. As if to underscore those points, Random House Chairman Peter W. Olson and company President Erik Engstrom note in a year-end letter to the staff that 129 of the 412 “notable books of 1998” recognized by the New York Times were published by Random House imprints. “We will finish this calendar year, and very likely our fiscal year on June 30, stronger and more prosperous together than we ever would have individually,” the letter says.

In 1999, just as the radio, banking and health-care industries, to cite but three, continue to be dominated by fewer, growing operators, so the book-publishing business may be jolted by further consolidation.

Romanos, the Simon & Schuster president, said that he hears from the “highest levels” of Viacom that it will hang on to S&S.; “Publishing fits into Viacom’s entertainment picture,” he stated. “We’ve been able to do a lot of business with Nickelodeon, ‘Star Trek,’ Paramount and the other Viacom brands.”

But buzz persists that Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. may wish to sell HarperCollins Publishers. High-ranking publishing sources say that Time Warner, the parent of Little, Brown and Warner Books, almost acquired HarperCollins this year, but no agreement could be reached on the price.

At the same time, the borderless market created by the Internet poses new and difficult questions about territorial rights. A literary agent need not sell book rights to a French publisher before a reader in Paris can get the same book from Amazon.com, which does 22% of its business with customers in more than 160 foreign countries.

“Boundaries need to be redefined in the whole industry,” said Naggar, president of the agents’ group. “This is a major revolution we’re in, like the invention of the printing press.”

However, the revolution and the consolidation also offer encouraging evidence that books still matter. Indeed, in 1998, Bertelsmann, Barnes & Noble and Pearson made long-term investments in a form centuries older than the Internet.

Paul Colford’s e-mail address is paul.colford@newsday.com.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.