Hersch Nails Monk Solos

- Share via

One of the great tests of jazz pianists has always been how effectively they can deal with music that is not their own. Many of music’s finest practitioners--even those with substantial catalogs of their own compositions--have spent the majority of their performance time, on recordings and in live dates, exploring the works of other composers.

Why is it such a test? Because--especially for pianists, who have a virtual orchestra of sounds at their fingertips--dealing with standard tunes means finding an original perspective on another artist’s vision. And doing so in a way that preserves the original character of the music, while investing it with the performer’s own creative insights.

Thelonious Monk’s own initial recordings when he signed with Riverside in 1955, in fact, were dedicated to standards and Duke Ellington songs. And Fred Hersch, a gifted composer in his own right, has already done albums devoted to Billy Strayhorn, Rodgers & Hammerstein and others.

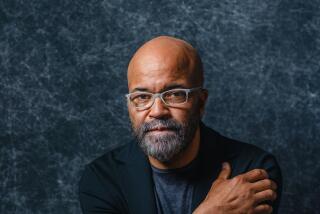

The recordings are among the 15 that the Cincinnati-born Hersch, 42, has recorded as a leader, two of which have been nominated for Grammys. His two-decade career has also included gigs with, among others, Eddie Daniels, Joe Henderson, Art Farmer, Stan Getz and Charlie Haden. Praised for his sensitive musical diversity, he is also a favored accompanist for singers such as Janis Siegel of the Manhattan Transfer and soprano Dawn Upshaw.

Still, despite Hersch’s eclectic skills and the growing popularity of Monk’s works, the choice to do the music in solo piano performances seems a daunting one, only rarely attempted by anyone other than Monk himself. But the results are remarkable--thoughtful, compelling renderings, with Monk’s music emerging in images never quite seen before. (Hersch will be performing this material at the Jazz Bakery on Feb. 9.)

Hersch, for the most part, wisely chose to avoid simulating Monk’s style, instead applying his own broad-based skills to the music. A few pieces--notably “In Walked Bud” and “Let’s Cool One” --surge forward with solid swing momentum, the former with a sometimes-rhapsodic touch, the latter with an undercurrent of stride rhythms.

More often, however, he views each work as a cameo, rendering them with the same precise articulation he would employ with a Chopin etude or a Bach prelude. The results are consistently fascinating, filled with ear-catching riches: the delicate, spidery opening of “Ask Me Now,” the five different takes on “Misterioso,” the subtle deconstruction and bombastic reworking of “I Mean You,” the two variations of “ ‘Round Midnight.”

That Hersch is a classically trained pianist is apparent in the fluency of his articulation and the great timbral variety he brings to his touch. But jazz-based improvisation is at the heart of his music, and it permeates every track.

Concept albums don’t always deliver results commensurate with their packaging. In this case, however, for Hersch to test his skills against the demanding Monk catalog was not only a good idea, it was an idea that produced an engaging jazz album.

*

Albums are rated on a scale of one star (poor), two stars (fair), three stars (good) and four stars (excellent).

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.