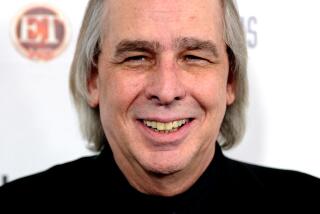

Country-Music Historian, Deejay Hugh Cherry Dies

- Share via

Veteran country-music disc jockey Hugh Cherry, who didn’t just spin records but was a drinking buddy of Hank Williams, gave career-launching airplay to Loretta Lynn when she was an unknown and became recognized as an authority on the history of country music, has died.

Cherry, who lived most of the past 38 years in Seal Beach, died of lung cancer on Oct. 15, at age 76. From 1946 to 1976, he worked as a country-music deejay in Louisville, Nashville, Cincinnati and Los Angeles.

After retiring from full-time broadcasting, Cherry produced radio specials and frequently spoke on country music, including lectures at Vanderbilt University, Stanford and Cal State Long Beach.

Cherry was a Kentucky farm boy, a self-styled “hillbilly” who in conversation could swing back and forth between the folksiness of his upbringing and the urbane, deep-voiced polish he acquired through his long broadcasting career. He was inducted in 1977 into the Country Music Disc Jockey Hall of Fame, a montage of plaques in the lobby of the Opryland Hotel in Nashville.

In a 1988 interview in the small, dimly lit ocean-side apartment he called “my book-lined cave,” Cherry told The Times that he retired because he had seen where country radio was heading, and it wasn’t to his liking.

“I had a 28-year-old program director, and his idea and my idea of what country music was just didn’t jibe,” Cherry said.

Chuck Chellman, who founded the disc jockey hall of fame, had this to say about Cherry in a 1988 interview: “He is one of the most misunderstood people, because he’s so honest and opinionated. And his opinions are usually backed up by an immense number of facts. Hugh Cherry is a walking encyclopedia of the country-music industry.”

Cherry had some wonderful, illuminating stories about Hank Williams, such as the time Williams gave him multicolored calfskin boots, then got mad at Cherry for never wearing them. When Cherry finally did put them on, it was during a snowstorm because he didn’t want to ruin his dress shoes.

As it happened, a drunken Williams came upon him on the street. “He said, ‘Cherry, you’re an ungrateful so and so. The first time I see you wearing those boots, you’re wearing ‘em in six inches of snow.’ He said, ‘Gimme those boots.’ He took the boots, and I walked the remainder of the distance to [the hotel Williams had just teetered out of] in my sock feet.”

A few weeks later, Williams returned the boots with a bottle of scotch inserted in each one and a note that said, “Don’t wear the boots in the snow. Use the whiskey to keep your feet warm.”

“Our common ground was hillbilly music and booze,” Cherry said of his friendship with country music’s greatest figure. “We liked both of ‘em.”

Cherry said his alcoholism ruined three marriages, but he eventually did something about it, quitting drinking in 1978 and becoming a lecturer and group leader for a privately run alcoholism education program in Torrance.

He remarried his first wife, Ouija Drake, in 1995 and moved to Houston with her, said Susan Trankle of Phoenix, a daughter from Cherry’s third marriage. Cherry returned to Seal Beach last year after his wife’s death.

In his later years, Trankle said, cycling became her father’s passion. “He rode 50 to 70 miles a week, right up until his diagnosis [of cancer in July]. He lived for it. It changed his life.”

Cherry credited cycling with restoring his health in the late ‘80s after a bout of emphysema. Timothy Cherry, the son who prodded him to start riding a bike, was killed in a bicycling accident in 1989 at 27, and his father became a campaigner for bicycle safety.

“He was working on his memoirs, which he never got very far on,” Trankle said. “He talked about that up until the very end.”

Instead, fittingly, Cherry left his voice to country music’s posterity. Trankle said she retrieved 25 to 30 boxes of tapes from his apartment--interviews and old broadcasts, much of it on reel-to-reel tape.

In accordance with Cherry’s wishes, Trankle and her brother, Michael Cherry of Tullahoma, Tenn., will donate the archive to the Country Music Foundation in Nashville, the organization that oversees the Country Music Hall of Fame.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.