This Is Greatness No One Could Pin Down

- Share via

CHICAGO — . . . Like you remember where you were when Elvis died. That’s what you’ll remember, where you were if he retired. ‘Cause I’ll tell you something, when Michael Jordan retires, there’ll be a lot of problems, because we have a lot of young talent but Michael Jordan is something you can’t replace.

He’s Jesus in tennis shoes.

--Jayson Williams, New Jersey Nets

*

I knew Mike. Oh boy, did I know Mike.

I feel like the ancient Dustin Hoffman character in “Little Big Man,” creaking, “I knew Gen. George Armstrong Custer, for what he was and what he wasn’t.”

I knew Michael Jordan for what he was, the greatest basketball player ever to lace up a new pair of $125, named-after-himself sneakers before every game and a genuinely nice guy besides, and what he wasn’t, the All-American boy-next-door, an image he courted.

As a player, he was like something descended from heaven. Fellow greats Magic Johnson and Larry Bird, who would have been 1-2 picks for best player before He arrived--with Jordan, hyperbole was never the danger, sacrilege was--all but knelt at his feet.

In 1986 when Jordan, then a second-year pro with the lowly Bulls, hit the Celtics for 63 points in a playoff game, Bird, who usually took note of opponents only to sneer at them, said he was “God disguised as Michael Jordan.”

Johnson, who once signed to play Jordan one on one for money until the league nixed it, later noted, “We did what we had to do. Nobody can take away [Bird’s] three championships, my five championships but we’re not sitting here, thinking that we were better than Michael Jordan.”

For peers, fans, the press, watching him was a privilege--basketball raised to the level of an art form, an unscripted, competitive ballet, dominated night in and night out by a single dancer who leaps and pirouettes high above the others, leaving them worn out and twitching on the stage.

From my perspective, it was a privilege, a lot of fun and a pain in the rear. He was as much commercial entity--forget about $100-million contracts; between his $33-million contract and estimated $70 million in off-court deals, he might have grossed $100 mil last year--and cultural icon as basketball player. It was as easy to get an audience with the pope.

Around Mike, the press found itself reduced to paparazzi, firing questions out of the crowd. I once spent 10 days with the Bulls, doing a piece for Esquire, without being able to talk to Jordan alone. We did arrange a photo shoot--he was happy to do that but flatly turned down the magazine’s request for him to pose with Dennis Rodman--but his deal on exclusive interviews was to keep promising he’d talk to you in the next town, and the next, and the next. . . .

I had known it always went that way, and besides, Jordan always said plenty in the group sessions. However the editors, dismayed, reopened negotiations with Mike’s scheduler, Barbara Allen, from agent David Falk’s office.

Word came back: If I would fly back to Chicago, Mike would sit down with me.

I flew back, went to a Saturday practice and saw Mike. He explained, pleasantly as ever, he had to do “NBA Entertainment” today, and see a dentist, etc.

I flew home. The editors called a few days later to tell me Allen now said Mike had cleared time for me--on Wednesday of that week--and where was I?

I closed my piece with that story, noting I had to go home for my daughter’s wedding. She was 2 at the time, but I was afraid I might miss it, waiting to sit down with Mike.

Only Marginally of This Earth

Are you of this Earth?

--Foreign journalist, 1992 Olympics

Well, I come from Chicago.

--Jordan

No one could have set out to become Michael Jordan, since the position didn’t exist before he created it. But he didn’t lack ambition. If they filmed his life, it would look more like “Predator” than “Space Jam.” In real life, Mike might eat Bugs.

He was one of five children of James, a mid-level manager, and Deloris, a bank official, in Wilmington, N.C. A late bloomer, he later told of worrying about his big ears and taking home economics courses to learn how to cook, in case he could never find a wife.

Wasn’t that sweet?

He slew his inner dweeb fast. He lived to compete, throwing himself into anything he tried. Lightly recruited until his senior year at Laney High, he burst into prominence, became a McDonald’s All-American, landed a scholarship at . . . drumroll . . . North Carolina, started as a freshman, rare under Dean Smith in the days of four-year players, and then beat Georgetown with his famous 16-footer in the 1982 NCAA final.

Clearly, a young man moving that fast didn’t have to worry about late starts. He starred in the 1984 Olympics under Bob Knight, impressing even that most demanding of tyrants as the best he’d ever seen.

Then he turned pro and was drafted . . . third.

As promising as Jordan looked, no one saw actual transcendence in him, not even the Bulls, who drafted him after Houston had taken Hakeem Olajuwon and Portland had selected Sam Bowie, a journeyman-to-be who would be forever marked by the pick.

“We thought [Jordan] was going to be good or we don’t take him third in the draft,” said Kevin Loughery, Mike’s first pro coach. “We also thought he was a franchise player. But never could we have fathomed he was gonna be the best player ever to play.

“You look back, in college, he played the passing game. Then he went to the Olympic team, they also played passing game. But when we put in one-on-one drills the third day, we saw he had the ability to take the ball any place on the floor that he wanted to take it and that he could do things that shocked us.

“Then about two weeks into the camp, you find out he was about as great a competitor as you’re gonna find. Then you know you got a great player.

“And then, you know, the guy walks in the gym the first day as a rookie coming out of college early, an early entry in the draft, and he’s the leader immediately--so he had the whole package.”

Well, not quite the whole package. Jordan’s NBA career can be divided into two, by decade.

In the ‘80s, he didn’t pass much; didn’t trust teammates who were, first, old hacks and then, kids like Scottie Pippen and Horace Grant, often dismissing them (“my supporting cast”) while winning only individual honors.

In the ‘90s, he settled down, wised up and, as his teammates grew up, started the last, great dynasty of the 20th century.

The hits started happening:

* 1988-89--Makes “the Shot,” a floating 20-footer over Craig Ehlo that will be replayed at least 10 million times, at the end of Game 5 to KO the Cleveland Cavaliers in the playoffs.

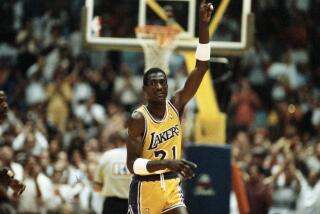

* 1990-91--Leads the Bulls to a 4-1 rout of the Lakers for his and the Bulls’ first NBA title. In the pivotal Game 3 at the Forum, he drives the length of the floor in the closing seconds, beats Byron Scott and makes a 17-footer over Vlade Divac to force overtime.

* 1991-92--Greases Clyde Drexler in the finals as the Bulls oust the Portland Trail Blazers in six. Hits so many three-pointers in Game 1, he turns to Magic Johnson, at courtside for NBC, shrugs and turns his palms up, as if to say, “How do I know where it came from?”

* 1992-93--Leads the Bulls over the Phoenix Suns, 4-2, in the finals, after postseason turbulence. During the season, a $57,000 check written by Jordan to a convicted felon named Slim Bouler surfaces. Mike says it was a loan, to help Slim open a driving range. Months later, in court, he admits blithely that he’d lied, he was paying off a golf debt. Sensational stories of his gambling exploits dog him through the playoffs, with a tell-all book by a friend, Richard Esquinas, claiming that Jordan lost more than $1 million to him at golf. Through it all, Jordan leads the Bulls back from a 0-2 deficit against Pat Riley’s Knicks in the Eastern finals. They dispatch the Knicks, 4-2, and the Suns in the finals, 4-2.

That summer, Jordan’s father is murdered. A few months later, Michael retires, referring to the press as “you all” 38 times at his farewell press conference.

Well, nobody said being king of the world was always going to be easy, or fun.

It’s Not Nice to Laugh at Michael

I remember one play. They’d been driving down the middle, so I said I’d take a hard foul on Michael. The next time down, he hit me in the side of the head and said, “Don’t think I forgot about that.”

He’s one of the most amazing men I’ve ever met.

--Jayson Williams, after ’98 playoff series against Bulls

In a further demonstration that Mike thought he was Superman--and in a rare failure that proved he wasn’t--he took up baseball, which he hadn’t played since his teens, announcing he wanted to make the big leagues.

Even with Bull owner Jerry Reinsdorf owning the White Sox and planning to call him up, just for the spectacle (and money), even with Mike’s presence dominating coverage of the national pastime as a ping hitter at double-A Birmingham, it didn’t happen. Jordan never said so but he hated to look bad and might have seized on the ugly strike that continued into the spring of 1995 as a pretext for leaving.

He rejoined the Bulls, looking rusty. But he wasn’t so bad he couldn’t drop 55 on Riley’s Knicks on a star-studded night in Madison Square Garden and then, double-teamed at the end, pass to Bill Wennington for the game winner.

But the Bulls were ousted in the second round of the ’95 playoffs, with Jordan fading late. Even admirers thought he was past it and dared to say it aloud, as when Orlando’s Nick Anderson, a friend, noted that No. 45, which Mike was then wearing, didn’t sky like old No. 23.

Basketball had never known the wrath of Jordan scorned. That summer, while in Los Angeles making “Space Jam,” he worked out daily under a portable dome, erected in the parking lot at Warner Bros., with weight room and full-court floor.

Jordan reported to camp lean, hungry and teed off. In one practice, he even punched little Steve Kerr, who had dared to oppose him in a labor dispute.

“Didn’t surprise me, especially the way Michael approached training camp,” Kerr said later. “I mean, he had a chip on his shoulder. He had something to prove. Every day was a war out there and he set the tone right from the beginning, the first day of camp.”

And the hits resumed happening:

* 1995-96--The Bulls win 72 games, breaking the Lakers’ old record by three, blitz through the playoffs with a 126-3 mark and win title No. 4.

* 1996-97--The dynasty riven with intramural strife, Mike signs for one year--at an unheard-of $30 million, after Reinsdorf hears that Falk is trying to work a deal with the Knicks. The Bulls, who are supposed to cruise to rest their old bodies, win another 69 games, making this the greatest two-season run in basketball history. The Bulls roll through the early rounds of the playoffs with only an occasional bump, like the Game 2 upset at the hands of the Atlanta Hawks in Chicago. A former member of the Bulls’ staff describes Jordan’s reaction:

“Mike walked in the locker room and he killed every one of those guys. Phil [Jackson, the coach] and [assistants] Jimmy Rodgers and Frank Hamblen and Bill Cartwright just leaned up against the wall. [Jordan] was going up and down the lockers--’You guys don’t know what it takes to win!’--he just killed them all. It was the greatest speech you ever heard. It was like Knute Rockne.

“And when he was done, Phil just said, ‘That’s it.’ ”

Then, in the finals at Salt Lake City, with the Bulls suddenly in trouble, Jordan, faint with flu, arises to score 38 points in the pivotal Game 5 in the Delta Center. He makes the game-winning 20-footer, of course, in the single-most stupendous game of an unbelievable career.

* 1997-98--The career is still going, even though the hour is getting late, for the Bulls as a unit, if not for Mike, personally. Jackson almost leaves but Mike persuades him to return. Jackson makes Reinsdorf fly to Idaho to re-sign him--for one more year. Jordan makes Reinsdorf fly to Las Vegas to re-sign him--for one more year, at $33 million. With Pippen injured, feuding with management and out until January, the Bulls, clearly over the hill, start 8-7, then, with the buzzards circling, finish 54-13, making it the best three-year run in NBA history.

They beat the Jazz in six again, with Mike making the last shot he may ever take--you never know about this guy, after all--to win the final game.

Jackson, without whom Jordan has said he won’t stay, leaves over the summer. The Bulls name Tim Floyd to replace Jackson--conditionally, depending on Jordan’s wishes.

The charade is on, for real. Reinsdorf and General Manager Jerry Krause, who let their relationship with Pippen deteriorate in the belief that the dynasty would be over before now, insist to the end they’re trying to keep the team together.

“The No. 1 objective we have here as a franchise is to bring Michael Jordan, to bring the championship team back,” Krause says Monday, amid reports Jordan will announce his retirement.

The No. 1 objective they have as a franchise is to make sure they don’t get blamed for running off the greatest player in history and ringing down the curtain on the dynasty before the play is over.

But it is. Jordan reportedly told Falk on Sunday night, Reinsdorf, Commissioner David Stern and teammates Ron Harper and Pippen on Monday. It’s all over but the quotes. Soon, he’ll belong to the ages.

*

“I feel responsible as a young player to try to carry on the tradition that he and other players have developed, both on and off the court.”

Kobe Bryant, Laker Guard

*

“He’s leaving with championships. He’s leaving with a ton of accomplishments. But the NBA will be all right. I think the league will survive without a dominant, Michael Jordan-type player.”

Grant Hill, Detroit Piston Forward

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.