FANCY FREED

- Share via

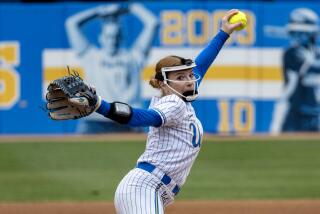

You come to UCLA’s Easton Field looking for the nation’s best freshman softball player. She won just about every award a high school player could have won. She has been named Pacific 10 player of the week twice this season. She joined the country’s best team and immediately established herself as its No. 2 pitcher. And when she wasn’t pitching, she played some spectacular left field. She hit with power and finesse.

Her name is Amanda Freed. You know that much. She played at Pacifica High last year. And then you begin looking around as the Bruins are warming up for a doubleheader against Washington. You spot a tanned girl in the bullpen pitching with such force that you hear the ball hitting the mitt of the catcher from across the field.

The girl throwing these pitches seems so fragile, though. Her legs and arms, from a distance, look so thin. You wonder how she is making the ball become a blur, where that power could possibly come from. Then you see her number and realize that, yes, this is Amanda Freed.

Freed came to UCLA this season as the No. 1 high school player in the country, everybody said so. Freed was the 1998 Gatorade Circle of Champions national player of the year. She was first-team All-American as a junior and senior. She was twice California player of the year. Her high school pitching record was 64-5.

No expectations there, right?

But as UCLA prepares to host an NCAA regional this weekend, it turns out Freed has fulfilled all those expectations.

Since the Bruins’ No. 1 pitcher, sophomore Courtney Dale, was named Pacific 10 pitcher of the year, Freed has done well for herself to be No. 2 and compile a 24-4 record on a team that is 55-6 and ranked No. 1.

When she’s not pitching, Freed chases fly balls in left field with the long, smooth strides of a middle-distance runner. When one line drive was hit, it seemed certain to become a double or triple. But the ball never had a chance to hit the ground. Casually, Freed made an over-the-shoulder catch.

And as a hitter, Freed batted .362. She’s No. 3 on the team in runs scored (42) and in hits (71). She’s second on the team in stolen bases (nine in 10 attempts). In other words, there is nothing Freed doesn’t do well.

There has not been one disappointment associated with Freed, says UCLA Coach Sue Enquist. And that hasn’t been easy for Freed, her coach thinks.

“The expectations were so high for this girl,” Enquist says. “She had no chance to just quietly fit in or get into a groove. She was expected to dominate from Day 1. She had already set the standard so high and that’s what’s so impressive. She set her own standard so high and she has managed that pressure very well.”

As women’s sports have become more and more well-funded, mostly with the legal help of Title IX, which mandated that colleges offer equal athletic resources to men and women, women have come to face some of the same pressures as men.

If more awards are handed out, if more national publicity is being received, if recruiting is becoming more and more national, and if all that is a good thing for the women, then there is also another side. There is more pressure. There are expectations. If you receive a full scholarship and get your name in USA Today and win an award sponsored by a sports drink company, then you’d better not come to college and bomb out. You’d better win. You’d better hit. You’d better field. Now.

When you talk to Freed, she has a soft voice. You strain to hear it. She is incredibly modest. Her face reddens when she is asked where all her power comes from. She has a pipsqueak voice and an arm seemingly made of spaghetti. She has ankles no wider around than a Coke bottle and wrists smaller than that, and yet when she throws a softball, it can leave a breeze.

“It’s kind of amazing,” says Ernie Parker, a respected Orange County pitching coach who goes up to UCLA on Wednesdays to help Freed.

“She’s always been small. Her size kept her from pitching for a long time, even though that’s what she wanted. Until she had a growth spurt in high school, Amanda was a shortstop. Now, I think she’s one of the best pitchers in the country. I’ll bet she didn’t tell you that she made the 60-person roster to try out for the Olympic team.”

Parker is right. Freed never mentioned that.

But as you watch Freed throw an eye-crossing variety of pitches, fast and slow, as you watch her make the softball do a crazy two-step, up and down, rising and falling, while batters twist themselves around trying to make contact, you begin to see that her talent is special.

“I just learned a new off-speed pitch from Ernie last week,” Freed says. Her eyes turn serious even while her mouth grins. “It was fun to use it today. It seemed to work.”

There. That’s it, says Enquist. That’s what makes Freed special.

“She’s an excellent athlete,” Enquist says. “No doubt about that. Watching her pitch, that’s physics in motion. She is extremely efficient. But, and you wouldn’t know it by looking at her, Amanda is the toughest competitor on this team. She really is. Nobody wants to win more than Amanda. And she’ll do what it takes.”

And about that pressure. There is none. That’s what Freed thinks. At least not from any outside expectations. Because nobody else can expect as much from her as she expects from herself.

“She wants to be the best,” says Karen Freed, Amanda’s mother and a pretty fair softball player herself. “She always has. But a long time ago Amanda and I talked about this. We agreed that she always had to play softball because it was fun, first and foremost. There will be disappointments and failures along the way, but if you play the game for any other reason than because you love it, things get too hard.

“I think Amanda’s done a good job of keeping it that way.”

Having brushed a tear from her cheek 15 minutes earlier after she had given up one home run, just enough to let Washington beat the Bruins, 1-0, in the season finale, Freed was smiling again. She talked about pitching, the science of it and the emotions of it. She talked about UCLA and about the NCAA tournament. The more she talked, the more she smiled. Because, after all, fun is the thing. Her mother said so.

*

Diane Pucin can be reached at her e-mail address: diane.pucin@latimes.com

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.